A new article appears in the latest Planet (216, Winter 2014) looking at nation-building, as well as wider issues of British and American influence with regards to our contemporary cohort of post-1997 poets. You can also find previous articles, exploring the genesis and aims of the project (‘From Back-story to Afterlife’), and the rise of women in the post-1997 context (‘Writing through the glass ceiling’), in Poetry Wales, issues 49.2 (Autumn 2013) and 49.3 (Winter 2013/14) respectively. Many thanks to Emily Trahair, editor of Planet, and former editor of Poetry Wales, Zoë Skoulding (very recently interviewed by Devolved Voices here), for providing space within their pages to explore the aims, and some of the observations and outcomes, to date.

Recent interview additions to the Devolved Voices collection

The Devolved Voices interview collection is continuing to grow. Recent additions to the collection include Philip Gross, Anna Lewis, Zoë Brigley, Patrick McGuinness, and Jonathan Edwards. Please do also explore the many fascinating interviews now housed on our site!

In the middle of it

The middle part of the Devolved Voices project has been all about building up the bulk of our materials and analysis.

Most obviously, perhaps, Kathryn Gray has been adding wonderful material to the library of poets who have been interviewed for the project’s online media section. So do look out for fascinating upcoming videos of Zoë Brigley, Patrick McGuinness, and Philip Gross. These pieces struck me as having, between them, real intellectual bite, as well as moments that were rather moving. Of course, each interview also has a companion video of the poet in question reading from his or her work, so it’s three such ‘doubles’ that are on their way soon.

Over the same time, I have been trying to carve out a series of lectures about a range of poets who have established themselves since 1997. Choosing which poets to write about has been something of a challenge – there are many you could make a strong case for looking at. The basic idea here (to which I’m committed by the project’s original proposal) is that I should produce detailed studies of eight writers who I think have some sort of significance – by which I suppose I mean that I think their work is valuable in some way (although perhaps I just enjoy it myself!), or that it has gained a certain cultural currency. These studies are intended to be delivered as lectures in the first instance, with each of them subsequently being turned into an individual chapter in a book that will bring them all together.

I had originally thought to restrict my work to writers who have produced more than one full collection by the point in time that I was writing about them. But after a while it became clear to me that I needed adopt a rather different structure: I had to look at a couple of poets who emerged early in the devolutionary period (with first collections within about five years of 1997, such as Samantha Wynne-Rhydderch), a couple of poets whose first collections came out roughly ten years after 1997 (such as Meirion Jordan), and a couple of poets whose first collections are only just upon us (in the period fifteen-years-plus since 1997). The first of this latter pairing that I’ve chosen to look at is Jonathan Edwards, whose debut volume My Family and Other Superheroes came out from Seren only this year. It is one of the privileges of this particular project that I can spend serious time thinking about such a new writer, whose warm-hearted – heart-on-the-sleeve? – engagements with family and locality have made me hope for much more poetry to come from him. (Take a look here for his recent New Welsh Review guest blog post about his writing.)

These three temporal categories give me six of my eight poets. However, to complete my eight, I realised that I wanted to look at two poets who are strongly situated within what might be called a neo-modernist or neo-avant-garde tradition. John Goodby has argued for the importance of modernism to the work of Welsh poetry in English since the 1930s (see note below). And as John and I clearly share a sense of issues and material that need to be explored here – some years back, I wrote the beginnings of an attempt to unearth a ‘radical’ Anglophone Welsh poetics since the 1960s – I wanted my current series of lectures to have a dedicated space for poets who I see as working self-consciously within this particular literary context.

The lectures and essays that will (I trust!) be the upshot of all this are not an attempt to provide some sort of overview of post-1997 Welsh poetry in English. But I do hope they’ll constitute an interesting attempt to provide extended readings of poets whose work is, I think, significantly visible – in one way or another – within the field.

Note

In his article ‘“Deflected Forces of Currents”: Mapping Welsh Modernist Poetry’, Poetry Wales, 46/1 (summer 2010), pp. 52-8, John Goodby suggests that ‘what makes Anglophone Welsh poetry most distinctive is its pronounced modernist origins’ (p. 52). Indeed, he argues that, for Welsh poetry in English, ‘alternative poetry’ is ‘not so much “parallel” to a mainstream as that mainstream itself’ (p. 58).

In conversation with Joe Dunthorne

An interview with the poet and novelist Joe Dunthorne is now live on the Devolved Voices website.

Interviews with Dai George, Kate North and Nia Davies

The latest addition to the Devolved Voices website is a trio of fascinating interviews with Dai Geprge, Kate North, and new editor of Poetry Wales, Nia Davies. You can also browse the library of existing interviews by either clicking on the links to the right or using the drop-down ‘Media’ menu.

Reviews and reach

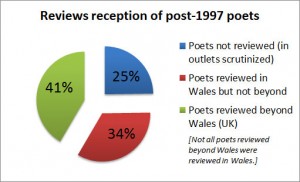

As part of our work on the Devolved Voices project, researcher Kathryn Gray has compiled a bibliography of reviews of work (pamphlets and collections) by our post-1997 cohort of poets. Drawing on this, Kathryn has compiled statistics illustrating the reach that our cohort has had in terms of reviews coverage. The team will be talking about this in detail at the upcoming 2014 Association for Welsh Writing in English conference at Gregynog, but here’s one taster of some of the data we’ll be presenting.

The following pie-chart divides our post-1997 cohort of Anglophone Welsh and Wales-associated poets into those whose pamphlets/collections:

- have received no reviews in the outlets we have scrutinized (see Note 1 below);

- have been reviewed in Wales but not beyond;

- have been reviewed in the wider UK.

Please click on the pie-chart to enlarge it.

Notes: (1) For a run-down of the publications that have been scrutinized as the basis for our data, see the introductory notes on the Reviews Bibliography page. (2) The information presented in this pie-chart is based on the following current data as collected by Kathryn Gray for the project: [a] an overall post-1997 cohort of 101 poets; [b] 675 reviews of pamphlets/collections by poets within this cohort (or 710 reviews, if hard-copy and online versions of the same review are counted individually).

Interviews with Jasmine Donahaye, Ian Gregson and Katherine Stansfield

Pleased to be able to post three very interesting new interviews with poets Jasmine Donahaye, Ian Gregson, and Katherine Stansfield (who is due to debut with Seren later this year) on our Devolved Voices website today. We thank them for their time and their participation.

Click on the links to the right to access – and please do explore the Media archive, which to date also houses interviews with Damian Walford Davies, Matthew Francis, Richard Marggraf Turley, Meirion Jordan, Rhian Edwards, Pascale Petit and Tiffany Atkinson.

New interview added to the website

The latest poet to be added to our collection of interviews is Tiffany Atkinson, whose third collection of poetry, So Many Moving Parts, was published by Bloodaxe last month. Follow this link to view the video. You can also browse the library of existing interviews by either clicking on the links to the right or using the drop-down ‘Media’ menu.

Poetry and public issues

John Redmond’s recent book from Seren, Poetry and Privacy: Questioning Public Interpretations of Contemporary British and Irish Poetry (2013), puts forward an argument that poetry is all too often read automatically alongside public issues. Poetry is thus, Redmond suggests, contorted to fit one social theme or another. By contrast, what he wants to argue is that if you scratch at such public interpretations of poems, they tend to flake away – with poems often being revealed as much more fundamentally expressions of a private state.

So, for example, Redmond argues against a historicist reading of Derek Mahon’s ‘A Disused Shed in Co. Wexford’ (i.e. that it is bound up with The Troubles) to suggest that its primary theme is actually ‘consciousness’:

The poem, I will argue, is not about history. It is about consciousness. What gives the poem its complexity are the conflicting attitudes towards consciousness which it keeps in play. (p. 40).

Similarly he writes against the helpfulness of seeing Robert Minhinnick as an eco-poet, suggesting instead that Minhinnick’s work is best understood through a very different rubric:

For all his environmental activism, what we overhear in Minhinnick’s poetry is not ‘the song of the earth’ but a song of myself. (p. 108)

Again, the brief reading of David Jones in the book’s final chapter proposes that the best way to understand Jones’s work is through the notion that he was ‘a weaver of his own fictions, […] a self-creator’. Thus:

First and foremost, his books were a tremendous performance. […] I am not suggesting that we ignore the versions of the world to which he drew attention, but am suggesting that we dwell a little more on that from which he draws our attention, the performer and his performance. (p. 191)

For a project such as ‘Devolved Voices’ which is, precisely, constructed around the public matter of Wales’s post-1997 devolutionary story, we do well to bear in mind Redmond’s caveats about public and private interpretations of poetry. At the simplest level, what his book seems to suggest for our purposes is that writing which emerges from a devolved context does not always have to speak to that context. Or to put that somewhat differently, and to echo issues raised by Jasmine Donahaye in the book Slanderous Tongues, a sort of ludic play in poetry of the early devolutionary period does not necessarily point to a sense of post-devolution confidence. To misappropriate a phrase from Freudian apocrypha, sometimes ludic play is just ludic play. The poem, to put it differently again, does not have to become a figure for, or an allegory of, its socio-cultural context – specifically, in our case, the devolving state of Wales.

I don’t think Redmond is arguing against the proposition (which seems simply basic to me) that literary works are inevitably products of their times and places, and that they emerge out of influences and knowledge-banks that are available at a given moment in a given location – however much such influences, such times and such places may be filtered, shifted, digested, resisted and variously worked over to create a particular piece of literature. But he clearly has issues with what is done, critically, within that sort of broad context. So, when he discusses an interpretation of Mahon offered by Hugh Haughton, he argues:

The contention seems to be that since the poem [‘A Disused Shed’] was written during a particularly violent phase in the Northern [i.e. Northern Irish] conflict, the poem must be about that period. This is hardly a convincing line of argument since it would arbitrarily bind all poems to any events that occur in their immediate historical radius. (p. 43)

I understand the nature of Redmond’s objection: don’t assume that, just because a poem was written during particular circumstances, it has to be about those circumstances. Indeed. However, I don’t think Redmond’s second sentence at this point necessarily follows his first: just because one poem seems compellingly to do with its generative circumstances patently does not mean that all poems must be so read. That is a question for the nuances of critical judgement, from case to case.

But Redmond’s fundamental point here seems sound to me and really very simple: the most helpful, most revealing way of reading a poem isn’t necessarily through the public issues of its time and place – although I simultaneously want to maintain that every poem is, in complex and over-determined ways, bound (to take Redmond’s word) to its generative socio-cultural context in the same way as it is bound to the generative psychological context of its author.

Notwithstanding such caveats, Redmond’s warnings against deterministic or simplistic ways of reading that box poetry into ready social categories, trends, and events are clearly useful. A project of literary analysis done under the sign of devolution must not contort its poetic subjects so that they all point, in obedient critical fashion, in a neatly devolutionary direction.

Matthew Francis and Richard Marggraf Turley

Two further videos of poets now available online at our website: Matthew Francis and Richard Marggraf Turley.

Also at our website, you can browse our bibliography of collections and reviews of poets under our post-1997 scrutiny, as well as other materials of interest to all those engaging with Welsh poetry in English. You can also join our Facebook group for regular updates on newly available materials. And we welcome you to follow us on Twitter.