Disclaimer: The website goes into detail on issues that some may find distressing e.g. sexual assault, rape, abuse

What makes life for women in the military so hard?

This project explores recruitment vs reality for women in the military. Women when being recruited for the military are promised many things, and in reality face many difficulties that are ultimately quite traumatic, including bullying, harassment, discrimination and assault. Therefore it is important to look at why this occurs. What makes life in the military so difficult for women?

Recruitment

This is the first video you find on the UK military recruitment page specifically for women. Titled “A soldier is a soldier”, this recruitment video presents the military as a progressive institution that works beyond the barriers of gender to promote equality, something the video makes a point of showing isn’t the case for women in many other jobs.

This video is the second placed on the same recruitment page. This video is used specifically to reassure women concern abut enlisting, about gendered issues.

For example:

“What happens if I get my period? Will I have to share a room with men? What happens if I have or want to have a family? Will I always be cold muddy and uncomfortable?”

These types of questions are frequently asked by women when considering enlisting, presenting a gendered difference in the recruitment process

The recruitment process: A contradiction in terms?

When we view these two videos placed side by side, it is noticeable that there is a strong contradiction in the recruitment process for women. One video glorifies a lack of gender in the military, which ensures no one will be discriminated against, the other is a reassurance for women thinking of enlisting about specifically gendered issues. The UK military is therefore attempting to advertise itself as a genderless institution, while catering for gendered issues. This presents the military not as a gender free environment, but as a female-gender free one. This (unintentionally or not) presents the female-gender as a disadvantage if it is something to be ignored in the armed forces.

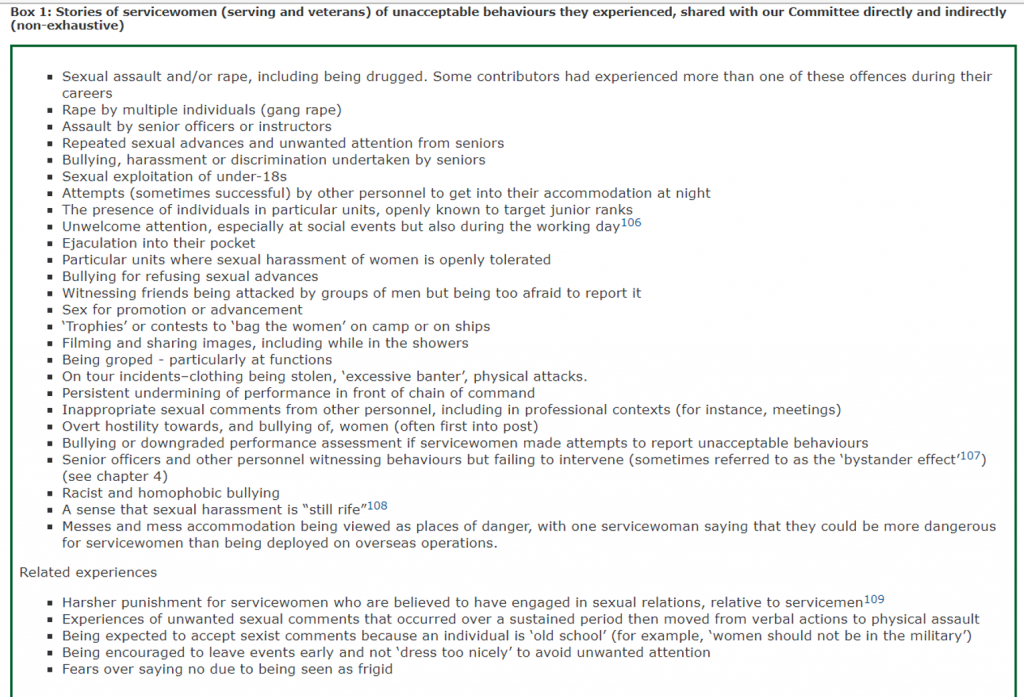

The Atherton Report

This report, published 25/07/2021, is a thorough investigation into women’s experiences in the military, (both current and veterans). The report states that, “64 percent of female veterans and 58 percent of currently-serving women reported experiencing bullying, harassment, and discrimination (BHD) during their careers.” Adding to this the report offers an extensive list of the types of abuses women have faced while serving: (warning: upsetting content in the next image)

What does the Atherton Report tell us?

This report shows an alarmingly high rate of bullying, harassment and discrimination that women in particular have to deal with. It also highlights the shocking difference between recruitment, where videos and literature present the UK military as a gender-free haven for women, and reality.

The Proof is in the Webinar

Part of the research conducted for this project included attending a webinar hosted by the UK Army titled ‘Army Officer- A Female Perspective’. A range of women hosted the event covering issues ranging from training to become an officer to hearing from the first female officer to become a corps colonel. The key attractions listed to entice women to undertake officer training was the sport, adventure and variety.

It was relatively obvious that this talk had taken into consideration the recent government report, as a specific reference to a female committee working on developing female fitted body armour was mentioned, also the notion of women being respected and promoted just as highly as men was a reoccurring comment made from all speakers. These were areas the Atherton Report had highlighted as particularly problematic.

The Contradictions are clear:

One Officer described how she felt she had always been respected as a person, and felt her gender played no part in how she was treated in the military. Then went on to describe how she nearly missed out on a tour of Afghanistan she wished to go on, due to ill-fitting body armour. This encapsulates what this research project is investigating. The army is pushing a genderless approach to recruitment, then consequently the treatment of women, however, trying to cater for specific gendered issues

Defence response to the ‘Women in the Armed Forces’ Report – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

The Ministry of Defence has responded the the Atherton Report, and generally it is a pleasing response commending those that have spoken out in the report and making significant pledges to change the culture and treatment of women in the armed forces.

However, the question remains that can this culture ever be truly reformed until gender is properly recognised?

Academic Literature: Gender Discourse and the Military

Natalie Jester (2021): ‘Army recruitment video advertisements in the US and UK since 2002: Challenging ideals of hegemonic military masculinity?’ Media, War & Conflict, Vol. 14(1). PP.57-74.

-Jesters article states that due to a recruitment crisis, the military (both in the UK and US) turned to societal groups they wouldn’t normally recruit from, such as women, or different ethnic groups, moving away from the military to be seen as a young white man’s domain

-Jester describes this as changes in, “discourses and practices positioning the army as less aggressive, less white and more female-bodied (perhaps even as progressive) serve to obscure militarized violence by repackaging it in a more palatable form” P.59.

-Jester reaffirms this research projects hypothesis that the military are recruiting from a platform of equality, [recruitment videos] “allude to the same point: that the army is a place in which traditionally oppressed groups will not be held back but can thrive. As a result of these representations, the army comes to be constructed as progressive.” P.69.

-However, Jester also goes on to note that the changes in these recruitment practises could potentially be harmful for women as they disguise the masculine nature of the military

Rachel Woodward and Patricia Winter (2004): ‘Discourses of Gender in the Contemporary British Army’, Armed Forces and Society, .PP.279-301.

Rachel Woodward and Patricia Walker’s article also presents how the military construct women and men as equal, this time specifically referencing the expansion of posts to women (albeit before women were welcomed in the infantry)

-They go into detail about the resistance to this expansion, based on the military being viewed as kind of sacred male domain. Stating, “Some interviewees for the project on which this article is based argued strongly that the symbolic importance of the figure of the (infantry) soldier as an exclusively male one could not be underestimated. According to this argument, the removal of the idea of combat as an all-male preserve is threatening and destabilizing to the Army’s collective sense of self as a masculine institution.” P.16.

-This links nicely with Jester’s article, asserting that the reason for focussed recruitment of women was a recruitment crisis, not the military actively seeking to diversify

-Woodward and Winter conclude with a word of caution: “we should be aware of the limits to that endorsement of female specificity and difference. Gender free physical selection is still gendered, in that it operates within a wider cultural context that privileges certain gender identities over others.” P.17.

-This adds to this research project, as Woodward and Winter comment here that while women have more access to the military and different positions within it, this doesn’t mean the military is a gender free experience as advertised, especially in an environment so traditionally masculine

Claire Duncanson and Rachel Woodward (2016): ‘Regendering the military: Theorizing women’s military participation’ Security Dialogue 2016, Vol. 47(1) 3–21

Duncanson and Woodward’s article significantly developed this project, deepening understanding of the academic feminist arguments for/against the inclusion of women in the military

-Duncanson and Woodward make key points that aid my research in terms of the product the military is selling vs what women receive: “While militaries may use the language of women’s rights and equal opportunities to fill the ranks, anti-militarist feminists contend that women are being duped, given the absence of full institutional commitment to progressive gender change” P.9.

-Their acrticle explains the discourses between some feminists that believe women shouldn’t enter the military as it is a symbol of masculinised violence that women should stand against, compared to what Duncanson and Woodward were promoting women’s inclusion in the military in order to make institutional changes

-This article reaffirms the research hypothesis that there is a contradiction in military practise in terms of gender

-Duncanson and Woodward explain the term ‘gender mainstreaming’ in their article, this aids the argument that the military are actively trying to recruit more women, expecting this to change the way women are treated and viewed in the military, while making no note-worthy gendered institutional changes.

-Gender mainstreaming is a perfectly valid explanation for the Atherton Report, and why despite the military being branded as gender free, simply adding more women hasn’t made it so.

The Regendered Soldier: A Message of Hope?

“A regendered soldier assumes a peacebuilder identity that is equally open to women and men, that equally values ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ traits, so much so that they cease to be masculine and feminine. In such a military, soldiering is not a masculine identity, but becomes much more fluid, and is constructed through relations of equality, empathy, care, respect, and recognition of similarities and shared experiences. The displacement of gendered dichotomies is immediately recognizable in this conceptualization. Not only are the meanings of masculinity and femininity questioned, but so is the valuing of masculinity over femininity and therefore the hierarchical thinking and material domination that has characterized gender relations.” P.12.

Taking this definition into consideration alongside the Atherton report, it is questionable whether the changes the MOD have promised to put into place will be effective. Until socially as well as institutionally, the definition of a soldier changes, can the UK military be more equal?

Cynthia Enloe (1988): “Does Khaki Become You? The Militarization of Women’s Lives.” Pandora Press, PP.1-220

“For it seemed to me that by revealing both how military forces had depended on women and had tried to hide that dependence, we, as women, could expose a vulnerable side of the military which is usually overlooked”P.1.

Enloe’s book is a brilliant insight into the military and how it effects all types of women and their lives, from army wives, nurses and prostitutes. Enloe explores how the military institution is so incredibly masculinized and why this negatively effects women.

This leads to an interesting debate, that contrasts with Woodward and Duncansons ‘Regendered-soldier’. Enloe presents, “That the military is so fundamentally masculinized that no woman has a chance of transforming that military into a place where women and men can be equal.” P.5.

For this research project, it created a crossroads. Should the reality for women in the military even be discussed if it cannot be improved? Will many more women not simply continue to suffer if equality in the military is continually promoted?

However, as Enloe so wonderfully points out, the ‘toxic’ culture of the military will be involved in woman’s lives whether they are participating in the army or not. This project suggests that equality can happen from within, and while gender-streaming isn’t an effective solution, cultural change can happen, and it is why reports such as the Atherton report are so important.

Reality: Veterans Studies

Maya Eichler: “Add Female Veterans and Stir? A Feminist Perspective on Gendering Veterans Research.” Armed Forces & Society 2017, Vol. 43(4) PP.674-694

An intersting catagoy that appeared when researching or this project is the reality of the military for veterans, not only did female veterans report a higher rate of bullying, harassment and discrimination (according to the Atherton report), but the discrimination does not stop there.

Eichler, goes into detail about the current status of gendered research, what is researched and what is ignored. The relevant take-away of this article for this research project is how abuses women face in the military are carried with them. For example “A study of Australian peacekeeping veterans found that family-related responsibilities, isolation in the field, or inadequate recognition experienced during deployment have significant impacts on women’s long-term health and well-being (Feldman & Hanlon, 2012). For example, rape during service affects the physical health of female veterans (Booth et al., 2012) and can lead to childlessness (Ryan et al., 2014).” P.679.

What Eichler shows here is that gendered issues are not only rife in the military, but they are often mishandled, and that these experiences negatively impact women as veterans. More research needs to be done for female veterans from a feminist perspective in order to properly recognise the gendered differences in experiences women have in the military.

Women and the capacity for violence

This research project has presented so far that there are differences in the way women are treated in the military, based on recruitment practises, the female gender is portrayed as something as a weakness that wont be taken into consideration so everyone is equal. Rejecting the female gender in the name of equality, implies that genders are not inherently equal in the first place.

Overlooking a woman’s gender in a violent setting doesn’t only apply to women in the military. Beyond the scope of this project ignoring womens capacity for violence has other consequences. It is worth presenting that feminist perspectives and gendered research is essential for national security as well:

“seeing gendered tactics as manifesting gendered strategies, and gendered strategies as selecting for gendered tactics. Understanding these complex relationships can provide a more accurate picture of how tactics are chosen and how they are performed. These linkages, however, not only aid the study of tactics specifically, but the study of war more generally”. Sjoberg, Laura. (2013). “Gendering Global Conflict: Toward a Feminist Theory of War”. Columbia University Press. Ch8. P.247

Women have been involved in both the war on terror, but also as active participants in acts of terrorism, “Al Qaeda and similar groups are likely to recruit women to carry out terror attacks. Indeed, in early 2003, American law enforcement officials learned that bin Laden’s organization planned to enlist women to infuse an element of surprise into the terror war” Nacos, Brigitte L. (2005). “The Portrayal of Female Terrorists in the Media: Similar Framing Patterns in the News Coverage of Women in Politics and in Terrorism”. Department of Political Science, Columbia University New York. P.447.

While this project isn’t about the study of women’s violence, it is clear that there are parallels between rejecting women and their capacity for violence within the military, and then rejecting the idea of women being violent actors in terrorist organisations. By refusing to take women’s violence seriously, not only does this negatively impact women’s experiences as female soldiers, but has real security consequences.

Conclusion:

Overall, this project has presented that there is a strong contradiction in the military recruitment process for women. The army presents itself as a genderless institution in which women wont be discriminated against. However, the military are then trying to cater for specifically gendered issues in the same breath.

This has significant consequences for women. First, recruiting on a genderless basis, is not the same thing as non-discriminatory recruitment (which is surely a good thing). Men are not being recruited on a genderless basis, only women, this carries this implication that a female gender is something that would otherwise hold a woman back. Therefore, the military isn’t a gender-free institution, it is a female-gender free one.

Second, despite all its ‘positive’ advertisement, the Atherton report clearly shows that women are still treated as an ‘other’ in the military. With women facing horrific abuses, there is clearly not the strong culture of ‘a soldier is a soldier’ as presented.

This leads to discourses of gender and the military as an institution. This project explores feminist arguments about whether the military should be avoided by women as a symbol of masculinised violence, or if we should strive towards a ‘regendered-soldier’.

Veterans research is also something that is effected by the complex reletionshop between the military and gender, as this project presnets how the poor treatment of women while serving, leads to long-term trauma’s.

Finally, the project makes reference to a further branch of research, and attempts to draw parallels between gender and violence within the military, and how this has consequences when considering women as security threats in terrorist organisations.

Acknowledgements

A huge thank you to:

Neil Gaff- Your experience and advice has been invaluable

Dr. Jana Wattenburg- For inspiration as a women in security studies, and pointing me towards the real questions

Dr. Chris Phillips- Brilliant advice and encouragement

Bibliography

Duncanson, Clair and Woodward, Rachel (2016): “Regendering the military: Theorizing women’s military participation” Security Dialogue, Vol. 47(1) 3–2

Eichler, Maya (2017): “Add Female Veterans and Stir? A Feminist Perspective on Gendering Veterans Research.” Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 43(4) PP.674-694

Enloe, Cynthia (1988): “Does Khaki Become You? The Militarization of Women’s Lives.” Pandora Press, PP.1-220

GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) – Defence response to the ‘Women in the Armed Forces’ Report.

Jester, Natalie (2021): “Army recruitment video advertisements in the US and UK since 2002: Challenging ideals of hegemonic military masculinity?” Media, War & Conflict, Vol. 14(1). PP.57-74.

Protecting those who protect us: Women in the Armed Forces from Recruitment to Civilian Life – Defence Committee – House of Commons (parliament.uk)

Sjoberg, Laura. (2013). “Gendering Global Conflict: Toward a Feminist Theory of War”. Columbia University Press. Ch8. P.247

Woodward, Rachel and Winter, Patricia (2004): “Discourses of Gender in the Contemporary British Army”, Armed Forces and Society, .PP.279-301.

Women In The Army | British Army Jobs – British Army Jobs (mod.uk)