“The pen is mightier than the sword[1]” are the words spoken by Cardinal Richelieu in Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1839 play Richelieu. The expression indicates that the written word is often more effective than violence as a means of political, organisational or social change. It’s a phrase which applies well to the Crimean War of 1853-56, arguably the first media war. During that conflict, the British newspaper press took full advantage of their freedom and independence to embed themselves with British forces on campaign in a hitherto unseen fashion to provide their readers with informative and engaging reports on the conduct of the British war effort. This experimental form of war reporting had a major impact on the image and reputation of the British Army in the reading public’s mind, which this work will detail. The areas this work covers include the exposing of rampant incompetence in the post-Waterloo Army’s structure and organisation, how the common soldier became both humanised and lionized and how these factors shifted the Army’s public image from being seen as a brutish instrument of repression to a broken organisation in dire need of reform. However, before delving into the Crimean War and the buildup to it, we must examine the historic context within which the British Army and the newspaper press evolved in the decades prior.

Section 1: (Very) Old Glory – The British Army post-Waterloo

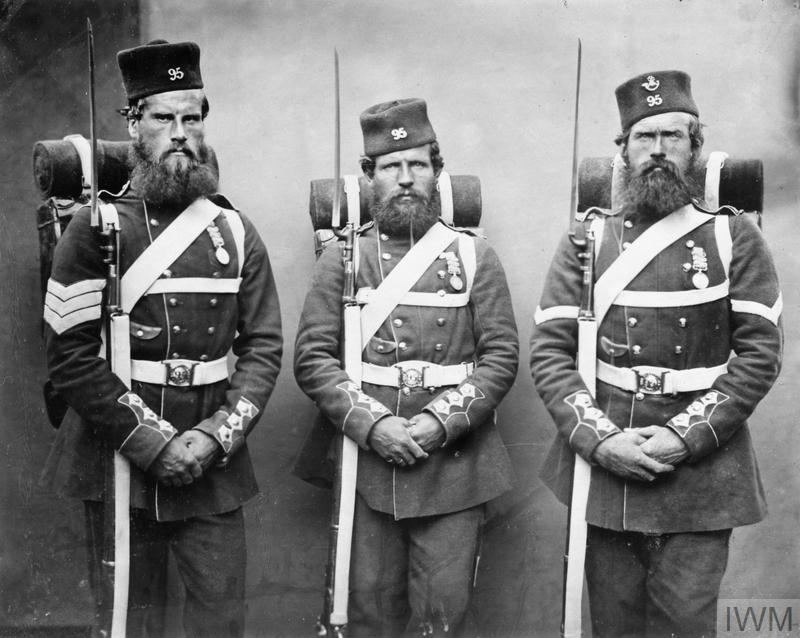

The British Army was described by the Duke of Wellington as the “scum of the earth [2]”, a quote perhaps fitting to describe the public reputation of the British Army in the early 19th century. In peacetime, the force writ-large alternated between being seen as anywhere from costly & unnecessary to a repressive tool of the state, contrasting with the patriotic and supportive mood the public held during times of war. A more specific analysis that the middle and upper-classes perceived the common red-coats as “coarse, drunken louts…lazy wastrels and…outcasts[3]” whilst the new working, poorer, class saw the Army as the “coercive means used to put down civil disturbances4”, effectively as militarised police used by the ruling class to keep them down. An example of why many perceived the Army as a repressive instrument is the 1819 Peterloo Massacre, in which the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry violently attacked and dispersed a peaceful reformist rally in St. Peter’s Fields, killing 17.[4]

Public mistrust wasn’t the only issue for the British Army in this period, it had aged beyond usefulness both literally & figuratively. Regarding the former, the eventual commander of the British forces – the one-armed Lord Raglan – was in his late sixties and his last experience of battle had been at Waterloo forty years earlier. In wasn’t much better elsewhere, as N. Gash describes: “Of the six divisional commanders in the British army in the Crimea all but two were over sixty[5]”, the Duke of Cambridge and Lord Lucan being the two exceptions.

Additionally, the structure of the Army remained effectively frozen in the 1810s. Supporting the Regular Army were poorly funded rear support forces such as the Commissariat (logistics) and medical branches that had seen their funding slashed by peacetime post-war governments to bare minimum. The army they sustained composed 102,000 artillery, cavalry, infantry and engineers composed the Regulars, of which 40,000 were stationed in the Empire as well as 26,000 serving the corporate East India Company.[6] Much of the reason the British Army structure changed so little was because of the elderly Duke of Wellington’s personal opposition to reform and the influence he carried as the victor of Spain and Waterloo: “‘While the Duke of Wellington lived,’ commented the Manchester Guardian, ‘no one ventured to question either the civilian or military administration in opposition to his great authority.’[7]” Overall, the British Army prior to the Crimean War was preserved in a Wellingtonian time capsule that prevented major reforms from taking place, led by elderly and increasingly frail officers and poorly equipped, whilst at the same time its enlisted ranks were widely dislike as uncivil outcasts.

Section 2: Hot Off the Press – The Development of the British Press in the Early 19th Century

The early 19th century saw many changes for the British newspaper press, British newspapers up to that point remained largely small operations that were often: “under-capitalised and produced in small workshops[8]”, limiting their circulation. What aided the popular press’s take-off was a series of technological advancements as well as the repealing of the stamp duty on newspapers.

The stamp duty on newspapers was created by the 1712 Stamp Act and was raised and lowered throughout its history, peaking in 1815 at 4d. (d meaning pence) a sheet.[9] Stamp duty was devised and continued largely to supress anti-government publications by making them too expensive for the poorer and middle classes to buy.

Stamp tax reform came in stages, being reduced from 4d to 1d in 1836 and being finally abolished after continued campaigning in 1855[10], ending the de-facto government censorship and restoring almost full freedom of the press.

The 1836 stamp tax reduction helped spur a publishing boom and a number of new newspapers were founded including the liberal-leaning Daily News in 1846 and The Daily Telegraph founded in 1855[11] shortly following the abolition of newspaper stamp duty.

Whilst the winds of change blew in the political realm, the press world was also being revolutionised in the technological world. As a case study, in 1814, The Times was able to increase its output to over 1,000 pages-per-hour when they began using the Koenig Steam Press, further increasing to over 4,000 per-hour in 1827 with the Applegarth press.[12] With increased production capacity came increased circulation, The Times saw over 40,000 copies in circulation by 1851, up from 5,000 36 years prior[13].

Further technological developments would aid press coverage in Crimea. One of these was photography, which had first been used to accompany news stories in the June Days rising of 1848 in Paris and would find itself further developed into war photography by the work of Roger Fenton which will be discussed later.

The second new piece of technology was the telegraph, which allowed news to be transmitted faster and with greater accuracy. It also stimulated a desire for greater professionalism and accuracy given that news could be relayed whilst it was still in-date. As Rachel Teukolsky notes: “Victorian newspapers continued an eighteenth-century tradition of expressing strong political opinions in editorial columns; but the invention of the electric telegraph in 1836 and Isaac Pittman’s perfection of shorthand in the 1840s led to a new reportorial investment in immediacy, transcription, and the eyewitness account.[14]”

Altogether, as the post-Napoleonic and early Victorian periods progressed, the British press became freer to report what it wished and more affordable to the reading public to consume.

Section 3: Pulling Back the Curtain – Army Deficiencies Revealed

Towards the end of the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy’s dog Toto pulls back a big green curtain, only to reveal that the wizard nothing more than a small man operating a pyrotechnic machine. This scene can be used as a metaphor to describe the revelatory process of discovery the British public went through as the once-victorious army of Wellington was revealed by the press to be far less impressive and capable than wished and expected. The influence of the press over the public’s view of the war was so great that it forced changes it government policy, particularly towards the supply and medical situation of the army in Crimea.

This section will deal almost exclusively with the impact of the press upon the British Army’s organisational and logistical flaws in Crimea rather than the common solider, which can be found in the next section.

Much of the press criticism of the Army in Crimea revolved around the inefficiency of logistical and medical provisions and the impact of that inefficiency among the frontline troops (particularly during the siege of Sevastopol), and on the apparent inability of the Army’s commanders to carry out the war efficiently and successfully.

For instance, articles concerning the medial condition and treatment of British soldiers during the Siege of Sevastopol caused outrage in Britain at the treatment of their soldiers, humanising them as their suffering became more widely understood. Additionally, the prefabricated Renkioi Hospital was commissioned and transported to Constantinople after an impassioned pleas for action in The Times such as the following:

“Meanwhile, a cry of distress and for additional comfort beyond those of mere hospital treatment came home from the East from our wounded brethren in arms. There instantly arose an enthusiastic desire to answer it.[15]”

The supply situation was also covered in detail by the British press. During the siege of Sevastopol from 1854-55, British troops were exposed to appalling conditions: “with the trenches flooded and no proper shelter for the troops when off-duty…Over the winter, lack of proper supply systems brought the British Army in the Crimea to the brink of starvation[16]” and thousands of men would die of diseases such as cholera. Again, it was The Times’s reporting of the situation that spurred the government into action, eventually leading to the construction of the Grand Crimean Central Railway, as can be read below:

“…men dying of cholera. After the battle of the Alma the wounded were carried down in hammocks, along between two…[unintelligible, reading quality poor]…carried by sailors in the [unintelligible] manner. The second day the French put their excellent ambulance corps at our disposal.[17]”

Whilst the image of the common enlisted soldier was being improved by the press, the image of their commanders plummeted as reports in the papers increasingly suggested that senior commanders were incompetent, unnecessarily increasing the suffering of their men on the battlefield.

For example, in the aftermath of the October 1854 Charge of the Light Brigade, the reputation of British cavalrymen was enhanced – the horsemen being seen as gallant heroes. On the other hand, the British commanders’ (Raglan, Lucan and Lord Cardigan) reputations suffered as the disaster was reported in British papers, such as in the following report from the Chester Chronicle:

“The Charge of the Light Brigade of Cavalry on the batteries of the enemy, some 30 guns strong, through brilliantly and bravely done, was disastrous in its consequences to that gallant and devoted band, for it seems that out of 700 who went into the fray only 130 answered their role call when it was over.[18]”

On the other hand, the British commanders’ (Raglan, Lucan and Lord Cardigan) reputations suffered as the disaster was reported in British papers, such as can be seen in the same Chester Chronicle report stating that “it appears to have been done under a misapprehension of an order from the Commander-in-Chief [Raglan].[19]”

Overall, the British press had a major influence in bringing to light the British Army’s structural and organisational failings and in improving the image of the common soldier via its reporting on the inability of the Army to provide adequate provisions and supplies for the troops on the frontline and in its coverage of the poor medical facilities to care for the men. This influence can be seen in changing government policy – such as the Crimean railway and Renkioi Hospital – that came about as a result as the increasing public awareness of the soldiers’ situation on the ground through the press’s reporting.

Section 4: The Hero’s Journey – The Lionizing of the British Soldier

On-the-ground reporting from the press began a process of lionization of the common soldier, which additionally served as an enhancer to the image of the enlisted serviceman.

For example, William Howard Russell reported in The Times of the 93rd Highlanders at the Battle of Balaklava, referring to them as a “thin red streak tipped with a line of steel[20]” which was misquoted as the famous thin red line, which came to represent stalwart resistance by an outnumbered and overstretched force.

A trend seen across reports from the Crimean War, and indeed from the thin red line, is that there are comparatively few tales of heroism and glory among the military commanders, indeed most press reports on the Army leadership were scathing.[21] Instead, the attention lay with the enlisted men, the common soldiers who fought often against likely chances of defeat.[22]

This glorification of the common soldier is a trend that continued after the end of the war in 1856. The image of the common soldier in the minds of the British public had begun to shift from seeing red-coated recruits as near-vagrants and lowlife to heroic warriors. As Myerly points out:

“The charismatic appeal of the military machine’s brilliant panoply was thus enhanced by its human components, who were not performers or actors, but real soldiers whose profession was associated in the public mind with glory, self-sacrifice and the defence of the realm.[23]”

Overall, the exposure the common British soldier received from the press in Crimea did much to improve the public’s image of them. The portrayals of soldiers in newspapers such as The Times as stalwarts holding off enemy advances such as at thin red line Balaklava, they turned the enlisted redcoat from a caricature to be derided into a heroic character to be revered and admired. This was in addition to the humanising of the soldier that was mentioned earlier on.

Final Thoughts

To conclude, the British Army’s public image and reputation was influenced and altered in many ways during the Crimean War, not all of which were for the better.

In the one hand, the once-triumphant army of the Duke of Wellington was shown to be little more than a relic unable to live up to the expectations that were expected of it. Alongside this was the exposure of the relatively poor performance of the elderly, aristocratic officer corps that had sent the Light Brigade to its demise, in addition to horrendous stories of soldiers dying due to logistical and medical inadequacies.

On the other hand, the story is far more positive. The common British soldiers were the subjects of better stories in the press’s publications. They were often portrayed as heroic stalwarts who did their duty even in the face of defeat and death such as the cavalrymen (minus their commanders) and the 93rd Highlanders at Balaklava. Whilst the stories of death and disease hurt the reputations of the British commanders, they humanised the individual soldiers themselves as the readers were able to empathise with their plight and eventual change government policy.

Those are the ways the press influenced the British Army’s public image and reputation during the Crimean War, some negative but some very positive. The end result of the Crimean War’s aftermath for Britain would spur reforms of the Army’s structure and officer corps whilst the enlisted soldier’s reputation remained strong as the British Empire expanded over the late 19th century, the press providing the British public with more heroic stories for their consumption.

Bibliography

2024. ‘Charge of the Light Cavalry Brigade’ – the Battle of Balaclava, 25 October 1854. 24 October. Accessed January 10, 2024. https://blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/2013/10/24/charge-of-the-light-cavalry-brigade-the-battle-of-balaclava-25-october-1854/.

Blanco, L. R. 1965. “Reform and Wellington’s Post Waterloo Army, 1815-1854.” Military Affairs 123-32.

British artillery officer. 1854. “THE ARMY IN THE CRIMEA.” The Times (London), 31 October: 1-12 https://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/archive/article/1854-10-31/9/1.html#start%3D1854-09-01%26end%3D1854-12-21%26terms%3Dcholera%20crimea%20cholera%26back%3D/tto/archive/find/cholera+crimea+cholera/w:1854-09-01%7E1854-12-21/2%26prev%3D/tto/archive/frame/go.

Brown, Michael. 2010. “”Like a Devoted Army”: Medicine, Heroic Masculinity, and the Military Paradigm in Victorian Britain.” Journal of British Studies 592-622.

Bulwer-Lytton, Edward. 1839. Richelieu : or, The conspiracy. A play in five acts, to which are added, Historical odes on the last days of Elizabeth, Cromwell’s dream, The death of Nelson. New York: Harper & Brothers. Available at: https://archive.org/details/richelieuorconsp00lytt/mode/2up.

from The Examiner. 1854. “WHO IS MRS NIGHTINGALE?” The Times (London), 30 October: 1-12 https://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/archive/article/1854-10-30/7/4.html#start%3D1854-01-01%26end%3D1854-12-31%26terms%3Dflorence%20nightingale%26back%3D/tto/archive/find/florence+nightingale/w:1854-01-01%7E1854-12-31/1.

Gash, N. 1978. “After Waterloo: British Society and the Legacy of the Napoleonic Wars.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 145-57 Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/3679205.

King, Ed. 2007. “British Newspapers 1800-1860.” British Library Newspapers. Detroit: Gale, 2007. Accessed January 09, 2024. https://www.gale.com/intl/essays/ed-king-british-newspapers-1800-1860.

Myerly, Scott Hughes. 1992. “”The Eye Must Entrap the Mind”: Army Spectacle and Paradigm in Nineteenth-Century Britain.” Journal of Social History 105-131.

Poole, Robert. 2006. “’By the Law or the Sword’: Peterloo Revisited.” History 254-76.

n.d. Siege of Sevastopol. Accessed January 09, 2024. https://www.britishbattles.com/crimean-war/siege-of-sevastopol/.

Special Correspondent. 1854. “THE WAR IN THE CRIMEA; THE OPERATIONS OF THE SIEGE.” The Times (London), 14 November: 1-12 Available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/archive/article/1854-11-14/7/1.html#start%3D1854-01-01%26end%3D1854-12-31%26terms%3Dthin%20red%20streak%26back%3D/tto/archive/find/thin+red+streak/w:1854-01-01%7E1854-12-31/1%26prev%3D/tto/archive/frame/go.

n.d. Taxes on Knowledge. Accessed January 09, 2024. https://web.archive.org/web/20131008073629/http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/PRknowledge.htm.

Teukolsky, Rachel. 2012. “Novels, Newspapers, and Global War: New Realisms in the 1850s.” NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction 31-55.

[1] Bulwer-Lytton, E. Richelieu : or, The conspiracy. A play in five acts, to which are added, Historical odes on the last days of Elizabeth, Cromwell’s dream, The death of Nelson (New York, Harper & Brothers, 1839) p.52

[2] Blanco, Richard L. “Reform and Wellington’s Post Waterloo Army, 1815-1854.” Military Affairs 29, no. 3 (1965): p.126. Available at:https://doi.org/10.2307/1984305. [accessed 08/01/2024]

[3] Myerly, Scott Hughes. “‘The Eye Must Entrap the Mind’: Army Spectacle and Paradigm in Nineteenth-Century Britain.” Journal of Social History 26, no. 1 (1992): p.105-06. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3788814. [accessed 08/01/2024]

[4] POOLE, ROBERT. “‘By the Law or the Sword’: Peterloo Revisited.” History 91, no. 2 (302) (2006): p.254. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24427836. [accessed 08/01/2024]

[5] Gash, N. “After Waterloo: British Society and the Legacy of the Napoleonic Wars”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 28, (1978), p.149. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/3679205 [accessed 08/01/2024]

[6] Blanco, Richard L. “Reform and Wellington’s Post Waterloo Army, 1815-1854.” Military Affairs 29, no. 3 (1965): 130. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/1984305. [accessed 08/01/2024]

[7] IBID, p.126 [accessed 08/01/2024]

[8] King, Ed: “British Newspapers 1800-1860.” British Library Newspapers. Detroit: Gale, 2007; paragraph 1 [accessed 08/01/2024]

[9] King, Ed: “British Newspapers 1800-1860.” British Library Newspapers. Detroit: Gale, 2007; paragraph 2 [accessed 08/01/2024]

[10] Spartacus Educational, Taxes on Knowledge. Available at https://web.archive.org/web/20131008073629/http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/PRknowledge.htm [accessed 08/01/2024]

[11] King, Ed: “British Newspapers 1800-1860.” British Library Newspapers. Detroit: Gale, 2007; paragraph 7 [accessed 08/01/2024]

[12] IBID, paragraph 5 [accessed 08/01/2024]

[13] IBID, paragraph 5 [accessed 08/01/2024]

[14] TEUKOLSKY, RACHEL. “Novels, Newspapers, and Global War: New Realisms in the 1850s.” NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction 45, no. 1 (2012): 31–55. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23259561. [accessed 09/01/2024]

[15] From The Examiner. ‘WHO IS MRS NIGHTINGALE’. The Times (London), 30 October 1854, p. 7

[16] British Battles, Siege of Sevastopol. Available at https://www.britishbattles.com/crimean-war/siege-of-sevastopol/ [accessed 09/01/2024]

[17] British artillery officer. ‘THE ARMY IN THE CRIMEA’. The Times (London), 31 October 1854, p. 9

[18] British Newspaper Archives, Charge of the Light Brigade – the Battle of Balaclava, 25 October 1854. Available at https://blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/2013/10/24/charge-of-the-light-cavalry-brigade-the-battle-of-balaclava-25-october-1854/ [accessed 09/01/2024]

[19] IBID [accessed 09/01/2024

[20] Special Correspondent. ‘THE WAR IN THE CRIMEA; THE OPERATIONS OF THE SIEGE’. The Times (London), 14 November 1854, p. 7

[21] Brown, Michael. “‘Like a Devoted Army’: Medicine, Heroic Masculinity, and the Military Paradigm in Victorian Britain.” Journal of British Studies 49, no. 3 (2010): p.606-07. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23265380. [accessed 10/01/2024]

[22] IBID, p.606-07

[23] Myerly, Scott Hughes. “‘The Eye Must Entrap the Mind’: Army Spectacle and Paradigm in Nineteenth-Century Britain.” Journal of Social History 26, no. 1 (1992): p.115. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3788814. [accessed 08/01/2024]