Introduction

The British Army constantly evolves, and its outward image is a subject of this constant change. A focal point of this change has been the volunteer reserve component of the Army. Across all three services, the volunteer reserve components are part-time service people who usually have another full-time career. Existing in some form since the 16th century, part-time soldiers in the modern sense have been organised along different lines in the intervening time between that period and the modern day. But one constant in the intervening time was that the part-time soldier and the wider auxiliary forces he was a part of had characteristics that distinguished them from the Regular Army. These were the profile of the auxiliaries, meaning how they were seen and perceived. Their aesthetics, meaning their outward appearance, expressed through uniforms and regimental distinctions. And their presentation, meaning how they were promoted in an official sense. Initially, the auxiliaries were robust in these characteristics and had a high level of distinction from the Regular Army. However, a noticeable trend occurred wherein by the latter half of the twentieth century the level of distinction in most of the auxiliaries, and later the TA was minimal to non-existent. This trend tracks well with the frequent reforms to the army throughout the twentieth century. The aim of these reforms when it comes to the auxiliaries was further integration with the Regulars. This page will illustrate how the distinctions between the auxiliaries and the TA have gradually faded as the Army has become more integrated. Using the above characteristics to highlight changes.

The Auxiliaries

The auxiliaries had their own unique identity and culture of appearing distinct in the past, which was carried on to a small extent with the TA. Regimental distinctions in the Army today are not as cardinal as they once were in the day-to-day life of the Army. This is even more so with regimental distinctions between Regular and Reserve units. In the past hundred years, the regimental system of many distinct regiments, often based on localities, has faded. This often way of organising the army was often lamented: ‘Those who have written about it have been in no doubt about its importance.’[1] And the system applied to both regular and reserve units. As such auxiliary units were formed as regiments in their own right. Yeomanry and Militia Regiments mostly tethered to counties and urban centres or cities. This type of organisation meant they had their own societal quirks: ‘In agricultural areas in particular the social composition of the Auxiliary forces will conform to an almost traditional pattern.’[2] So the characteristics of the auxiliaries during this time were rather strong. Their profile was shielded from insipidity by running on the same tram tracks as the regimental identities of the regulars. The Volunteers, the first true part-time infantry soldiers separate from the Militia, actually achieved a high degree of integration in the 19th century. Where the Militia was balloted the Volunteers were initially local units of infantry volunteers. It soon became evident that these were easier to manage as integrated battalions. This sort of integration thus lowered the distinct profile of the auxiliaries even during this time when their distinctions from the regulars were otherwise very strong. Despite being a short-term trend, this is still a part of the wider long-term trend of distinctions disappearing.

That shows how integration was a constant factor in reforms to the auxiliaries. However, the profile of the auxiliaries around this time was also strengthened by the ways they were employed. It was throughout the 18th and beginning of the 19th century when the Militia and Yeomanry were considered the ‘Home defence piece’. The regulars were primarily employed in policing the Empire and therefore not seen by the country and the general public as often as any often the auxiliaries. Ergo the already strong profile of the auxiliaries is compounded. Their minute presence in local life across Britain, formed as they were, as regiments in the system that would become traditional and revered. Combined with their consistent presence in rarely being embodied for overseas service and only for home defence, means that their profile in Britain was massive. This was heavily leaned into with spectacularly large reviews of auxiliaries often taking place in the presence of the members of the Royal Family or colonels in chief: ‘King George III reviewed the Volunteers of London and the neighbourhood on many occasions.’[3] And members of the public in the tens of thousands would come to watch. That fact only further emphasises the initial strength of the profile of the auxiliaries. And this was at a time when there was no formal professionalisation or integration; the arrangement of the auxiliaries fit the needs of the period well. Meaning their distinctive characteristics were untouched.

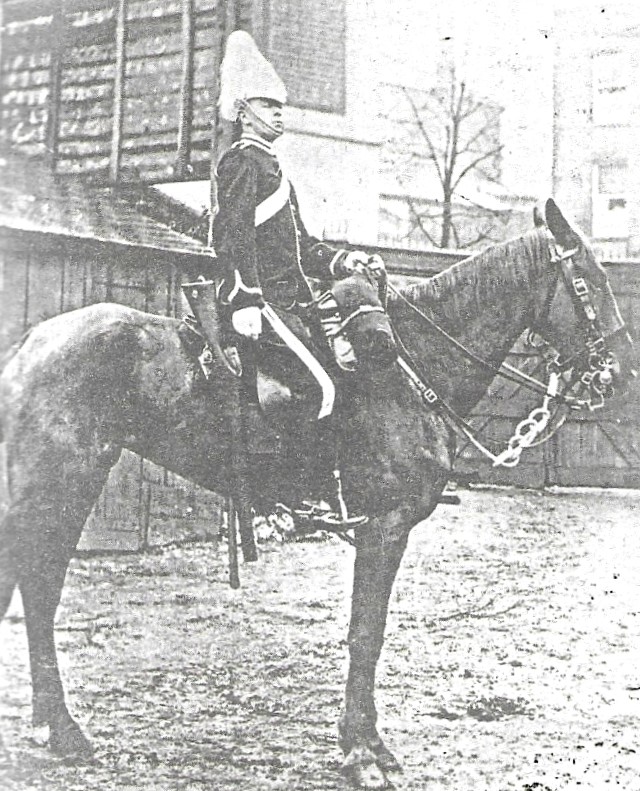

It’s unsurprising then that there seemed to exist a culture where aesthetic difference was prevalent throughout the auxiliaries. Sometimes to a surprising degree. Minor aesthetic differences were common throughout all of the auxiliaries. Gold facings (those that were a part of the base uniform, not those earned by distinction), for instance, were for a long time used mostly to distinguish the regulars. The closest any Auxiliary infantry regiment would get in the 18th century was perhaps the Honourable Artillery Company[4] with their adoption of silver facings. Which remain to this day. But there major differences too, the Yeomanry of the 18th and 19th centuries flaunted distinctive and elaborate full-dress uniforms, often worn as service dress. Which to some degree seems to outstrip the necessity of their function as static ‘ever-readies’ and aiders to the civil power. But this is indicative of the change that would eventually arrive. Otherwise, it seems that the 18th and 19th centuries were the peak of aesthetic differences between regulars and auxiliaries. This is linked to this period being the peak of separation of the Regular army and the three strands of auxiliary forces (Volunteer, Yeomanry, and Militia). Before the first reforms of the 20th century, the separation of these forces created an environment in which visual distinctions for the auxiliaries could be indulged. In practical terms, there was no reason why regulars and auxiliaries shouldn’t be distinguishable from each other. Integration is what changed this, and ushered in the start of the decline of the distinctiveness of the three auxiliary strands.

As what would become the TA became more integrated its profile became more akin to that of the regulars. Advertising was one of its last distinct features. The 20th century and the conflicts at its start were the impetus for this change to begin. The Territorial Army in its modern form originated with the Haldane Reforms in 1908 but integration in the sense we’re looking at began even earlier. Some organisational changes happened in the late 19th century, like Territorialisation in 1871; moving away slightly from the county-heavy auxiliary organisation and towards national organisation. The first incremental changes were brought in during the Boer Wars, which were overall a time of great change for the Army anyway. These conflicts were thus far the largest instance of Auxiliaries and regulars operating together. This profoundly changed the profile of the auxiliaries. For the first time, the auxiliaries were perceived in a major sense as overseas soldiers, as opposed to ever-readies defending the home country. This sense of professionalisation; the auxiliaries working integrated with the regulars in conflict, would continue as further reforms came. But importantly, the auxiliaries who performed best in the Boer Wars were infantry Volunteers. The Militia. despite having the largest presence, was confined mostly to rear-echelon duties in both wars. As such they came out of both with their reputation declining: ‘The army burnished its reputation via active service throughout the period, while the militia’s meagre Boer War laurels were not enough to outweigh forty years of peacetime mockery.’[6] Thus the Militia, one of the first auxiliary forces, was removed from the otherwise increased public view and burgeoning profile of the other auxiliaries (Imperial Yeomanry and Volunteers) during the Boer Wars. Bennett explores how the portrayals of the Militia at this time and after the Boer Wars contributed to its eventual axing. In short, the Militia’s profile was becoming exceedingly reductive and burdensome. This and other developments highlighted how the arrangement of three strands of auxiliary forces was past its due. Showing why the profile of the auxiliaries began to change at the start of the 20th century. Because the system of having three distinct auxiliary forces separate from the regular army itself was not as prudent as it had been. Without the legitimacy of this arrangement, there was no way for any of the auxiliaries to retain the unique distinctions they had had. And the culture of distinction was thus also becoming less eminent. It had been shown for the first time that the regulars and auxiliaries could operate alongside each other on a larger, properly integrated scale. Maintaining some idealized picture of the auxiliaries as distinct was becoming less necessary.

This is perhaps shown best through the changes in aesthetics and presentation. Practical changes like the change to Khaki were a result of the Boer Wars. None of the gaudy full dress of the Yeomanry or rifle-green and silver-blue of the Militia was practical. But this was an understandable change at a time when the gold and red of the regular army was also done away with. Something that contributed to both a change in presentation was the formation of the Imperial Yeomanry. While a practical move, this meant that Yeomanry regiments themselves weren’t sent to fight in South Africa: ‘Existing volunteers, Yeomanry and civilian recruits flocked to join the Imperial Yeomanry, though original yeomen would be in the minority; the traditional domestic yeomanry had a total strength of just over 10,000 and they were restricted to home service only unless they volunteered for the war.’[7] This wasn’t the case for the militia that went to South Africa with their regiments. But the formation of the Imperial Yeomanry was one of the first instances of real, on-paper integration in the time before the Haldane reforms. And carried some of the same reasoning. With the previously distinctive Yeomanry being reorganized and integrated for practical reasons and adopting a homogenous sense of presentation. The reasoning was that mass needed to be generated from the auxiliaries with more ease, and the “three strands” arrangement made that difficult: ‘The second Boer War had revealed significant gaps in both military capabilities and the ability to generate additional manpower from the auxiliaries in times of major crises.’[8] As such, the Haldane reforms brought all three strands together into the Territorial Force in 1908. This was the first major move towards integration across auxiliary forces in Britain. And outstretched the very incremental integrations mentioned above. All three of the strands were now defunct as individual auxiliary forces, and as such their characteristics significantly changed between the reforms in 1908, the Great War, and the interceding years before the Second World War. What Yeomanry regiments there were left ditched their horses: ‘After a stalled start, the Yeomanry had made a substantial contribution to the conflict, providing nearly 90,000 men for the war effort; nonetheless, half of them had not served mounted and the authorities had vacillated until March 1917 over their reorganization as infantry.’[9] And the Militia was fastidiously reorganized into the special and supplementary reserves before disappearing in the early 1950s. In terms of presentation and profile, the Haldane Reforms and subsequent reforms would have a mixed impact. With the auxiliaries and regulars now more akin to each other, they carried an overall more digestible profile. And after their contribution to the Great War, the auxiliaries of the TF were redesignated the Territorial Army in 1921.[10] This marked the beginning of a new era for the auxiliaries which would define them for most of the 20th century—one where their distinctiveness took on a different form.

The TA

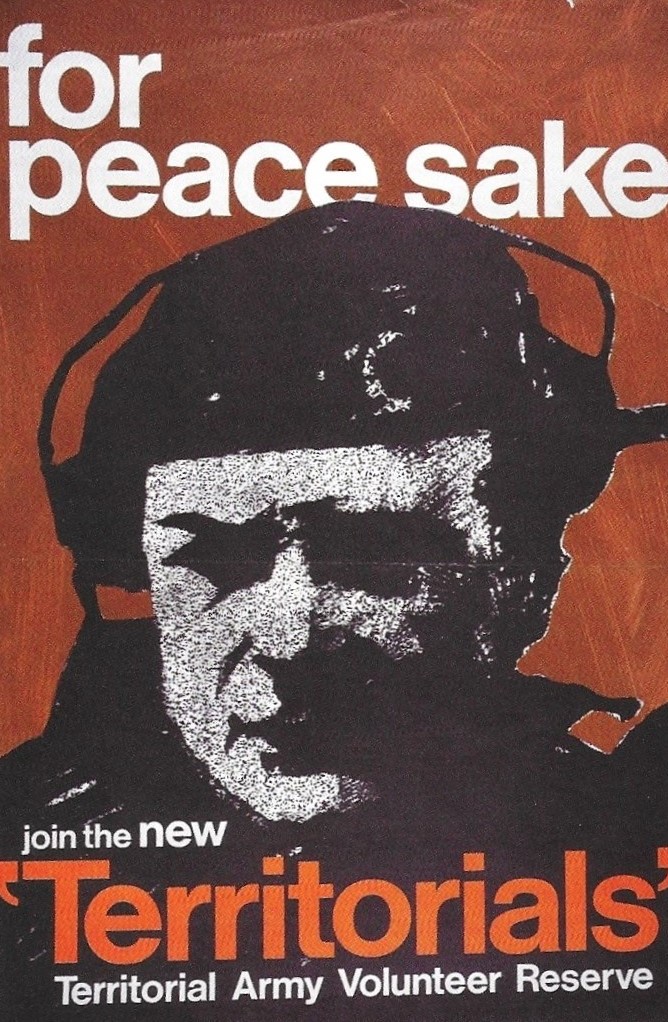

The name TA in and of itself would become iconic and be a driving force of the profile and presentation of the auxiliary/part-time soldier over the century. Proving the basis for the identity of the part-time solder as a ‘Territorial’. After both world wars, a high level of integration had been achieved. Major aesthetic distinctions were gone, and most differences could instead now be found in the way the Territorials were organised. This was mainly due to the circumstances of the late 20th century. The orthodoxy of the Cold War called for a sustained number of reservists. It was now possible to raise and sustain such a number thanks to the reforms of the past fifty years. As such, with recruitment being a constant concern, presentation through advertising became one of the main avenues of distinction. The TA was presented wholly for what it was; part-time soldiering. It was meant to appeal to the modern, working person and offer a somewhat different and more easily accessible experience compared to the regulars. In this sense, the TA was still to be perceived with a degree of separation and difference from the regulars. This distinctiveness in advertising was ensured by the TAVRAs (Territorial Army and Volunteer Reserve Associations), which ran recruitment. These organisations in and of themselves were a uniquity for the TA as they were the modern redesignations of the County Associations which had organised the auxiliaries previously. Elements like this still gave the TA a distinctive organisational profile compared to the regulars. But at the same time, the number of times the TA was redesignated and reorganized meant that advertising and recruitment were somewhat incoherent. For instance, the TA became the Territorial Army and Auxiliary Volunteer Reserve, or TAVR in 1967. And changed names several times thereafter But the TA nonetheless consistently leaned into its sense of presentation and advertising. Take for instance this excerpt from an initial recruiting poster for the TAVR: ‘Stop Wondering! This is the new Territorial & Volunteer Reserve. This new reserve, the T&AVR forming from the Territorials on 1 April 1967, will provide an ideal opportunity for men and women to use their spare time profitably in the service of their country.’[12] The TA still isn’t portraying itself as ‘the Reserve component of the army’ yet, but as a semantically separate body.

The latter half of the twentieth century, however, was still a period of flux for how distinctive the TA was. While the earlier period of strong distinctiveness through aesthetics was over. Throughout all the instances of integration that had occurred with reforms, redesignations, and the like. There was still a marked sense the TA was its own entity, able to present itself how it saw beneficial, and which had a profile still separate from the Regular Army. We can therefore establish that there is a wider trend that was present in terms of the TA’s image during the late twentieth century alongside the trend of integration. Held up to the strong distinctiveness of the auxiliaries in the past, the TA’s distinctiveness had declined due to integration and distinctions were no longer of the same eminence. And there no longer seemed to be a culture within the TA of retaining distinctive features since they had become so similar in appearance to the regulars. However, its presentation and profile were constantly fluctuating. With designation changes, reductions in the power of the TAVRAs, and cuts to the army as a whole. What this meant was despite the overall trend of integration, some iotas of aesthetic distinctiveness remained. The TA badge had been introduced for advertising and distinctive medals for volunteer service continued. Even units such as the Wessex Regiment, which was an all-Territorial formation, had unique accoutrements: ‘The Wessex Volunteers adopted the old 43rd (Wessex) Division’s Wyvern.’[14] But this smaller trend was what it was; fluctuating. The wider trend of integration was happening regardless. This was emphasized by changes like the final regional amalgamation of the TAVRAs and their eventual transformation into the RFCAs (Reserve Forces and Cadet’s Associations) meaning that one of the last distinctive organisational fixtures of the TA was gone. Another sign of integration. Overall what had by the end of the 20th century was a more systematic decline in the TA’s distinctiveness, despite some minimal revivals.

Present Day and Conclusions

As such, the army in the 21st century is at its most integrated. And the visual identity and distinctiveness of the TA and auxiliaries have been completely absorbed. Even if the profile of the modern reservist is still somewhat distinct; the reservist still has a profile in a practical sense. And in British society even if knowledge of the Reserves across the nation was not massive it was at least culturally substantial: ‘To many, indeed, despite the current high level of deployment, knowledge of TA is confined to the television series All Quiet on the Preston Front…and the character, Gareth in The Office.’ But at the start of the 21st century, despite still carrying its designation, the TA was presented as analogous to the regulars as possible. Iraq and Afghanistan even more so placed the profile of the TA within that of the Regular Army. Some regular units were seldom able to operate in these theatres without their Territorial counterparts and supporting Territorial elements. And those Territorials who stayed at home were still performing their role. Thus by this point, the presentation of the TA reached a sense of finality. With this and the dwindling size of the Army compared to the Cold War, the name Army Reserve was adopted, and the designation TA retired in a 2013 White Paper. Integration was firmly reason for this: ‘It would better signal that the Reserve is an integral and integrated part of the army delivering military capability at home and abroad.’ [16]

In conclusion, at this point we can observe the end of the trend we’ve explored. The auxiliaries had strong distinct characteristics in the past. These gradually faded as integration became more commonplace, and were retained to a small extent with the TA. Until the 20th century, distinct characteristics had been diluted due to integration, and today’s reservists are almost completely akin to the regulars in terms of visual identity. The extent to which integration had changed the auxiliaries, and now the reserves is thus marked. But these changes are perhaps beneficial; integration was always done with the purpose of creating a more effective fighting force for Britain. And this trend has perhaps reached its natural conclusion in the modern day as the army faces new challenges and new trends to adapt to.

I would like to thank Colonel (Retired) Patrick Crowley MBE DL. Author of Rose, Crown and Castle for his time in an interview conducted while researching.

Bibliography:

[1] French, D. Military Identities: The Regimental System, the British Army, and the British People C. 1870-2000 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 1.

[2] Beckett, I.F.W. ‘The Local Community and the Amateur Military Tradition: A Case Study of Victorian Buckinghamshire’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 59, (1981), p. 96.

[3] The Marquess of Cambridge. ‘The Volunteer Reviews in Hyde Park in 1799, 1800 & 1803’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 40 (1962), p. 117.

[4] Raikes, G.A. The History of the Honourable Artillery Company (London, R. Bentley & Son, 1879), p. 135.

[5] D.J. Knight Collection, cited in Crowley, P. Rose, Crown and Castle (Cowes, Medina Publishing, 2023), p. 91.

[6] Bennet, M. ‘Portrayals of the British Militia, 1852-1916’, Historical Research, 91 (2018), p. 336.

[7] Crowley, P. Rose, Castle and Crown (Cowes, Medina Publishing, 2023), p. 131.

[8] Crowley, P. Rose, Castle and Crown (Cowes, Medina Publishing, 2023), p. 155.

[9] Hay, G. ‘The Yeomanry Cavalry and the Reconstitution of the Territorial Army’, War in History, 23 (2016), p. 36.

[10] Crowley, P. Rose, Castle and Crown (Cowes, Medina Publishing, 2023), p. 493.

[11] Beckett, I.F.W. Territorials (Plymouth, DRA Publishing, 2008), p. 181.

[12] T & AVR Advert (Author Collection), cited in Crowley, P. Rose, Castle and Crown (Cowes, Medina Publishing, 2023), p. 357.

[13] Beckett, I.F.W. Territorials (Plymouth, DRA Publishing, 2008), p. 203.

[14] Crowley, P. Rose, Castle and Crown (Cowes, Medina Publishing, 2023), p. 364.

[15] Beckett, I.F.W. Territorials (Plymouth, DRA Publishing, 2008), p. 171

[16] Beckett, I.F.W. Territorials (Plymouth, DRA Publishing, 2008), p. 49.