Trigger Warning: This webpage discusses rape, sexual assault, and other sexual abuses some may find distressing.

Is it a microcosm for society?

To consider why the dismissal of sexual abuse within the armed forces is so common, it is important to first look at it outside of the army.

In the UK, 1 in 4 women and 1 in 18 men have been raped or sexually assaulted as an adult. 1 in 6 children have been sexually abused. 6 in 7 rapes against women are carried out by someone they know and 1 in 2 rapes against women are carried out by their partner or ex-partner. 91% of people prosecuted for sexual offences are men aged 18+. Only 2 in 100 rapes recorded by the police between July 2022 and June 2023 resulted in someone being charged within the year. Over 9000 sexual offence cases are waiting to go to court. 5 in 6 women who are raped do not report it to the police and the same is true for 4 in 5 men. 40% said they did not report due to embarrassment, 38% did not think the police could help, and 34% thought it would be humiliating. 6.5 million women in England and Wales have been sexually assaulted in some way since the age of 16.

These statistics show that not only is sexual assault all too common, but it often goes without being reported or charged. This is mirrored in the Armed forces.

https://rapecrisis.org.uk/get-informed/statistics-sexual-violence/

It is A Man’s World

Women make up 11% of the UK regular forces:

- 10.2% – Royal Navy

- 9.8% – Army

- 15.1% – RAF

- 15.2% – Reserves

Of ¾ interviewed for the Atherton report mentioned the inappropriate, ill-fitting uniforms and body armour which put them at greater risk.

War is often seen as a man’s only world and many people would see it as a masculine act from which women stand apart. Women, when referred to within the arena of warfare are often viewed through the tiny lens of “victim” of war or opposer of war and on occasion nurse. The truth, however, is quite the opposite, women are needed to continue war; women sustain the military. however, despite this necessity actually including women in the military brings into question this “natural” separation of women from warfare.

During training, to promote a sort of masculine bonding, there is an emphasis placed on the differences between soldiers and the “other”. This is often specifically about women as the “other”. They use marching chants that belittle women and describe rape, violent injury, or death at the hands of soldiers (Cohn, 2013, Chapter 6). Use of the word “girl” as a derogatory label for men who do not meet the standard. Any sign of failure or weakness is associated with femininity and is to be eliminated to be a proper masculine soldier. For a woman to be considered a ‘real solider,’ she must also eliminate her femininity and become ‘one of the boys’ but at the same time be a ‘real woman.’ An impossible paradox, that only leads to the conclusion that women are not designed to be part of the military, or realistically the military is not designed for women (Cohn, 2013, Chapter 6). Women soldiers are also often subjected to slander and innuendo concerning their morals, ability, and sexuality simply because they are women.

The Atherton Report

Report: Protecting Those Who Protect Us: Women in the Armed Forces from Recruitment to Civilian Life

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5802/cmselect/cmdfence/154/15402.htm

The following is a summary of the most relavent statistics and information from the Atherton report in order to illustrate the extent of the issue of sexual abuse in the Armed Forces.

Bullying, harassment, and discrimination were experienced by 62% of female service personnel and veterans, these behaviors include sexual abuse. In 2021, servicewomen were more than ten times as likely as servicemen to experience sexual harassment in the last 12 months. Approximately 84% said that female personnel face additional challenges in the Forces. 11% of female personnel in the Regs said they had experienced sexual harassment in the service environment in the last 12 months, compared to 1% of men (2021). 8% of servicemen and 21% of servicewomen had either experienced or witnessed sexual harassment at work in the previous 12 months. Servicewomen are more likely to report personally experiencing most types of ‘targeted’ sexual behavior. There is also evidence that it is more likely to be targeted towards lower-ranked servicewomen. For Criminal sexual offences, women were the majority (137, 76%) of the 180 victims in 161 investigations in 2020. 16 allegations of sexual assault were reported to the Service Police Forces by female Armed Forces personnel under 18 between 2015-2021. Commanding officers tend to have a lower number of complaints against them, most likely due to the hierarchy that protects the ‘important’ men and puts pressure on the lower-ranked women to drop the complaint or not complain because that ‘could ruin his career.’ 74% of veterans and 52% of serving personnel said the military does not do enough against BHD.

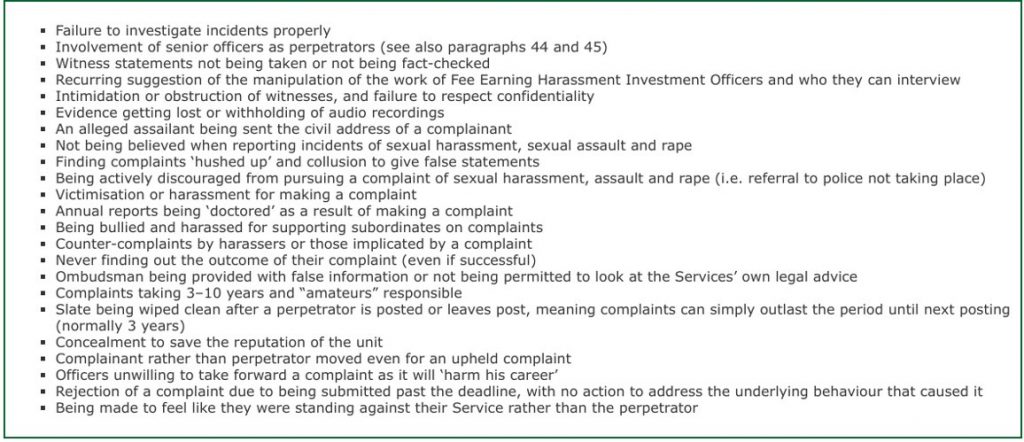

What Complaint System?

The following statistics are similarly from the Atherton Report used to illustrate the ineffectiveness of the current complaint system.

Servicewomen are 12% of Armed Forces but 21% of complaints, and of those 47% are due to BHD.

- 72% of all personnel were dissatisfied with the outcome, communication, and timing of their complaint.

- 70% of the complaints about sexual behavior were dissatisfied with the outcome.

- 75% said they suffered negative consequences as a result.

- 98% said they then felt uncomfortable at work.

- 93% thought about leaving.

- 92% lost respect for those involved in the process.

- 91% felt humiliated.

89% of service personnel in the Regs who have experienced BHD did not make a complaint.

- 55% thought nothing would be done about it.

- 49% though it would negatively impact their career.

In a whistle-blower article published as evidence by the Defense Committee, various cases were brought to light of the on-going sexual abuse against service personnel. The cases following are all taken directly from this report.

“A junior Officer who was sexually assaulted in her accommodation was cross-examined in the Court Martial by a military barrister while her attacker looked on; she refers to the experience as being ‘slut shamed by a future colleague’. Her assaulter was found guilty, but he was retained in Service. The Servicewoman is very conscious that she will most likely serve with (and potentially under) this barrister in future. She, therefore, constantly relives in her mind the assault itself but even more so the ‘slut shaming’ cross-examination. She thoroughly regrets coming forward despite the guilty verdict, as her professional, and personal, life has been ruined by doing so.”

“A Servicewoman who was being abused by a Serviceman in her CoC was unable to either stop the abuse or do anything about it, as she’d spoken with the woman in the Case above. She’d not disclosed what was happening to her, but the woman in Case 2 had told her what she’d gone through when she reported her assault. Having heard that story, this junior Servicewoman felt she’d rather put up with it until either she or he were assigned to another Unit than go through what that woman had been put through.”

“A junior Servicewomen reported as accomplished and performing far above her junior level was raped by someone she had previously been in a consenting causal relationship with. She didn’t initially report this for fear of recrimination and impact on her career. However, when she reported it to her GP, she was advised to ‘choose her partners more carefully in the future’. She was persuaded by another GP to report the incident to her CoC. However, on doing so, it was deemed by the CoC too important for the career of the rapist and the elite Unit he served in, to keep him in place, so she was moved across the country, out of the elite Unit, against her will, to an area she knew no one and had to live in transit accommodation where she would often hear unknown men in the corridor outside her room and would struggle to sleep, pushing furniture in front of the door and not leaving her room for days due to fears of the men outside her door. The move was presented as being to facilitate her access to therapy for the mental trauma from the rape but due to issues in the system it was far over a year before she got access to that therapy, which resulted in her being medically discharged from the Service, again against her will”.

Dyke or Whore?

Men often assume that any woman who joins the army must have done so in some way for a man.

There were rumors during WW1 that members of the Britian’s Womens Army Auxiliary Corps exhibited immoral behavior. Investigations confirmed that the rumors were unfounded and traced them to letters written by male soldiers who resented being transferred from non-combat duties to the trenches because of women (Cohn, 2013, Chapter 6).

Women in the military are caught in the “dyke or whore” conundrum. A female solider who chooses to have sex within the military may be labelled a whore, with questionable morals. If she does not have sex, she may be labelled as a lesbian regardless of sexuality. These labels are used to put down women and dismiss them from a place of importance or significance. It teaches male soldiers continuously to dismiss women as a serious part of the military and teaches women that they can only exist in the military through the masculine lens and not as ‘women’ as capable whole beings. This continuous harassment on top of sexual assault can lead to severe physical and psychological trauma, including PTSD. women who experienced sexual assault are more likely to develop PTSD than those who were exposed to combat. Being sexually assaulted by a fellow solider can prove extra-traumatic as it is from someone who is meant to be trusted to watch their back and potentially save their life. (Cohn, 2013, Chapter 6).

“Women may serve the military, but they can never be permitted to be the military.”

Cynthia Enloe, Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women’s Lives, Pg, 19.

The Normalization of Sexual Exploitation in Warfare

We cannot talk about domestic sexual abuse in the military without talking about the normalization of sexual exploitation across warfare, more specifically “necessity” of prostitutes by soldiers and rape as “inevitable” in war.

One of the biggest overlooked roles of women in warfare and the military is sex workers. The term “camp follower” is a derogatory term for prostitutes used by deployed military men. The women who were actively bought and arranged for protection by the Japanese military during the second world war were colloquially known as comfort women. Often these comfort women were teenage girls kept in conditions of slavery and subjected to repeated and brutal rape. During and after the Korean War, the US and South Korean governments ensured a steady supply of prostitutes for the US soldiers. Similarly, comfort women were supplied in the Vietnam War. US soldiers have, over the past six decades, not only used over a million Korean women as prostitutes; they have also been actively involved in trafficking Korean women to the US. (Cohn, 2013, Chapter 6).

British Military officials, during the late nineteenth century, found that troops deployed in overseas territories of the empire were more likely to seek sexual liaisons with local working-class women than the ‘proper’ middle class white women they were meant to. As such, the military officials worried more about venereal diseases. Due to this, various policies were put in place to attempt to decrease the access these women had to the soldiers, first through arrest and forcing lone working-class women to undergo vaginal exams. British military officials could not ‘lose control’ of Britain’s colonial women (Enloe, 2014, Chapter 4). Of course, there is a disgusting double standard of controlling women supposed immoral sexual behavior for the sake of protecting male soldiers supposed necessary sexual pleasures. Women must be available for male soldiers to have as they please to boost morale and health, but they cannot be seen to suffer such illegitimacy as a venereal disease that could have only of come from the lowly working-class foreign women.

In World War 2, the system of comfort stations gave rise to the concept of “sexual slavery”. Korean feminists argued that militarized forced prostitution should be considered a war crime. Similarly, American officials went to lengths to create racialized and segregated military prostitution system. Post invasion of Normandy, American soldiers set up brothels for stereotyped, oversexualized French women (Enloe, 2014, Chapter 4). These were women who were supposedly liberated by these soldiers. This racialized prostitution was continued from the Korean war, Vietnam war and war on terror. A common belief held by military officials is that prostitution ‘protects’ ‘respectable’ women.

One of the worst parts of the normalization of exploitation of women and the reinforcement of this hierarchy of masculinity and femininity is the way it makes sure women do not see each other as allies within it. The female soldier may not look at the comfort women or the military wife and see like or ally despite their potentially similar circumstances; they may look at each other and see an enabler. Women are constantly put down for anything they do and women on the outside of one area may look at the woman within that area through the same lens of disdain and dismissal that men have put over her. Women are not supposed to look at each other as natural allies because then they could have power. There are often even policies made within militaries that ensure dissimilar women within a base do not view each other as allies in anything. They are often successful. (Enloe, 2014, Chapter 4).

Whats the point?

The aim of this research is to show that the inherent heirarchy of the Armed Forces protects sexual abusers and continues to dismiss womens issues. The masculinity of war perpetuates this idea that a man’s career is somehow more important than the security of the serviceperson they have violated.

The constant dismissal of sexual abuses shows how ingrained people see it in warfare. Rape is often talked about as inevitable during war, whether it be as collateral or as a weapon. There is often a rise in domestic abuse in times of war and the immediate years after. The normalization of sexual exploitations in circumstances surrounding warfare is deeply entrenched in the preservation of the maculinity of war. That warfare was considered to be a man’s world, one that women were utterly separate from, is a view that still attempts to linger. Despite the point blank untruth of the statement, men do tend to be in the positions of power over women in these circumstances. As discussed, the targets of sexual abuse tend towards lower-ranked women, those in positions of little to no power. The conditions of war have only added to the entrenchment of sexual exploitation in the Armed Forces, from rape as a weapon against the enemy to the promotion of ‘comfort women’ for men’s ‘necessary’ needs. The military has constantly promoted a view that sexual exploitation is not just an unfortunate collateral of warfare, but intergral part of the system.

The patriarchal hierarchy provides cover for sexual exploitation by Armed forces personnel. Between the entrenchment of normalization and the abysmal complaints system it is no shock that there is little done about the sexual abuse that appears to be all too common.

Bibliography

Cockburn, C. (2010). ‘Gender Relations as Causal in Militarization and War’. International Feminist Journal of Politics. 12:2, 139-157, DOI: 10.1080/14616741003665169

Cohn, C. (2013). Women and Wars. Polity Press.

Duriesmith, D. (2014) ‘Is Manhood a Causal Factor in the Shifting Nature of War?’, International Feminist Journal of Politics. 16:2, 236-254, DOI: 10.1080/14616742.2013.773718

El-Bushra, J. (2003) ‘Fused in combat: Gender relations and armed conflict’. Development in Practice. 13:2-3, 252-265, DOI: 10.1080/09614520302941

Enloe, C. (2014). Bananas, beaches and bases : Making feminist sense of international politics. University of California Press.

The House of Commons Defence Committee. (2023) Damning whistle-blower evidence reveals ongoing sexual abuse within the Armed Services. https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/24/defence-committee/news/195323/damning-whistleblower-evidence-reveals-ongoing-sexual-abuse-within-the-armed-services/

The House of Commons Defence Committee. (2021) Protecting those who protect us: Women in the Armed Forces from Recruitment to Civilian Life. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5802/cmselect/cmdfence/154/15402.htm

Lee Koo, K. (2002) ‘Confronting a Disciplinary Blindness: Women, War and Rape in the International Politics of Security’. Australian Journal of Political Science. 37:3, 525-536. DOI: 10.1080/1036114022000032744

MacKenzie, M. Foster, A. (2017) ‘Masculinity nostalgia: How war and occupation inspire a yearning for gender order’. Security Dialogue. 48:3, 206-223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010617696238

Office of National Statitics. [Accessed via Rape Crisis]. (2023) Sexual offences prevalence and victim characteristics, England and Wales. ONS Link: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/datasets/sexualoffencesprevalenceandvictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales Rape Crisis Webpage Link: https://rapecrisis.org.uk/get-informed/statistics-sexual-violence/