‘The army has failed in its attempt to improve diversity within its ranks over the last 30 years’

In his first speech in December of last year the head of the armed forces Admiral Tony Radakin pushed for the army to do better in ‘reflecting the diverse nation’ it served.[1] The head of the armed forces recognising a lack of diversity surely means that the army has failed in its attempt to promote diversity within its ranks in the last 30 years? This project seeks to explore this question by highlighting army policy/strategies, personal opinions of soldiers, demographic data, and the current political climate of the United Kingdom.

BAME individuals have served in the British army for several centuries prior to the First and Second world wars. This became a normal occurrence during the reign of the British Empire when local armies were raised to protect the interests of Britain both from other citizens of those nations as well as foreign threats. In addition to this a few regiments such as the West India Regiment were formed to conduct overseas operations, drawing its ranks from slaves and less commonly free black people. During WWI, more than 1 million men from throughout the British Empire served both on the European Fronts as well as throughout Africa and Asia. This included 15,200 Jamaicans who all volunteered.

This was followed by WWII, which saw by the end of the war ‘over three million men’ armed and thousands of both women and men in supporting roles most of which where volunteers. The colonial legacy of Britain clearly cannot be separated from the discussion of race and the British Army, millions of BAME individuals over the last centuries have served the United Kingdom both voluntarily and involuntarily throughout the world.[2]

The British Army has been involved in 10 conflicts over the last 30 years and during this time the UK population has increased by 10 million. As of 2018, 14% are now from a Black, Asian & Minority Ethnic (BAME) background [3], despite the significant changes to the makeup of the UK; the military is perceived to be falling behind. This project focuses on the period between 1990 to 2021, during which the British Military sought to increase representation within its ranks as well as the treatment of its BAME soldiers.

This is a dense and complicated subject and so has been broken down into multiple discussions, first it will present an overall assessment of the British Army’s attempts. This will be followed by a description and critical evaluation of its policies and strategies, highlighting those that have been most and least successful. It will then dive into the intriguing nuances of the argument, as there is a variation in demographic representation between ethnic groups as well as commonwealth vs British Soldiers. The research project is then closed by discussing the missing answers to the question, this refers to the lack of recent data, interviews, as well as the socio-political climate outside the army which has a significant affect.

The following body of literature shows that although diversity has increased in terms of overall percentage representation of BAME individuals in the armed forces, the nuances in the data show that there is significant variation between different ethnic groups. Furthermore, there are difficulties in quantifying a success although the data does lead to the conclusion that there certainly is a failure in representation within the senior ranks.

Successes & Failures

The 1990s was the decade that saw the army pushed into the modern era in terms of diversity. A series of events both internal and external such as the murder of Stephen Lawrence which led to the release of the Macpherson report, in addition to multiple cases of racism internally where the catalyst for the 1998 Strategic Defence Review (SDR).[4] The release of the Macpherson report in 1999 led to an assessment of state institutions attempts to combat diversity during a time in which Britain was becoming increasingly multi-cultural.

The SDR highlighted the gap between ethnic representation in the population in comparison to the British army which was 6% vs 1%.[5] The Ministry of Defence (MOD) highlighted that the main goal was to focus on proportionality, stating that they wished to increase by 1% each year. There are many debates as to the importance of proportional representation in any workplace, nevertheless as the army set this as a goal for themselves it can be seen to be reasonable to assess their success through this measure. [6]

The UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 1 April 2021[7] shows BAME representation to be 9.2% in the regular armed forces which is less than the most recent population statistics for BAME citizens in the UK at 14%. Data on BAME groups in the UK was last released in 2018 and assuming it has been increasing this means that it is highly likely the difference between representation in the population and army has actually increased since the 1990s. By this metric the British armies attempts to increase diversity have been highly unsuccessful.

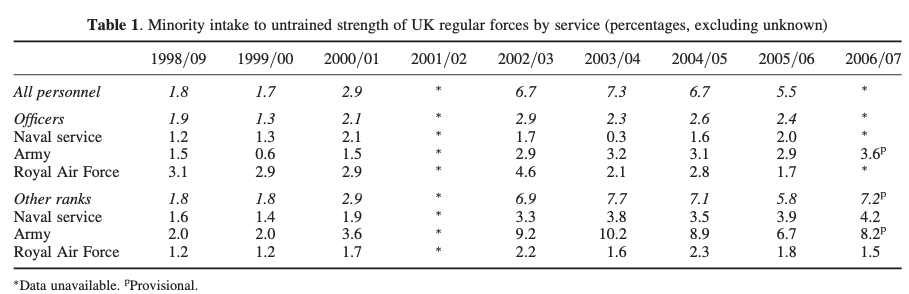

Despite the British Army failing to match BAME representation seen in the general population it has been successful in increasing representation overall. Despite ethnic minorities only making up 1% of soldiers in 1998 there has been a gradual increase in representation, table 1 presents the change in representation over the 8 years proceeding the SDR report reaching 5.5% by 2005/06. This has increased to 9% by April of last year, a significant improvement compared to the data in the 1990s. By this metric it can be said that representation within the army has increased, however it could be questioned whether a course correction away from data targets would improve recruitment.

The British army continues to base its success criteria on proportional targets that where first set out in the SDR over twenty years ago, a focus towards increasing the awareness of the benefits of diversity within the current ranks and an increased understanding of the effect of colonial legacies has on recruitment would benefit the attempts to meet targets.

Variations in ethnic groups, nationalities, and ranks

The discussion of diversity in the British Army so far in this project has highlighted the overall issue that underlies the attempts by the British army, providing key data on representation and the barriers to increase these percentages. This section dives deeper into the significant nuances in the debate, the first being the varying perspectives between BAME commonwealth and British soldiers.

Nationality and Diversity

In 2016 a doctoral thesis produced by Dr Balissa Greene shed light on ‘The Experience of Foreign and Commonwealth Soldiers in The British Army’, with support from the army Dr Green conducted ‘focus groups, semi-structured interviews and examined organisational documents’. The work concluded that the perception of Commonwealth soldiers was negative due to conflicting views of core ‘values, cultures and expectations compared to their white British counterparts.’[8]

Despite the earlier stated success in increasing ethnic minority representation in the army, a more detailed analysis of the data suggests that the attempt to promote diversity and inclusion has been far less successful. The aim of the SDR was to increase the connection between the British army and British society through increased number of ‘domiciled UK citizens’.[9] However, as a result of the perceptions of the British army being racist the MOD struggled to attract British ethnic minorities. This was evident in a survey in which ‘respondents were asked to give a reason as to why they felt ethnic minorities in the U.K were not joining’, 42% believed that racism was the key factor in this decision process.[10]

The failure to recruit within the UK in the early 2000s led to a campaign in the commonwealth which was highly successful and as a result in October 2020 40% of all ethnic minorities in the British Armed forces were not from the United Kingdom.[11] In addition, a drop in BAME representation in 2021 was result of recent policies to restrict commonwealth recruitment. Thus it can be said that although the army has increased representation overall, it has not increased the representation of BAME British soldiers.

Ethnic Groups and diversity

Breaking the data down into smaller ethnic groups such as Black and Asian also highlights issues in representation between ethnic groups. One of the most under-represented groups since 11th September 2001 has been South Asians. The most obvious and possibly significant reason for this is the alienation of Islamic communities both in British society and the army, a result of British military engagement in the Iraq and Afghan conflicts as well as the rise in Islamic fundamentalism. There are however other factors to be considered, one being ‘rational decision-making in occupational placement’.[12] The last 30 years have seen a rise in mobility within BAME groups, as a result the attractiveness of a career in the army in comparison to other occupations has likely decreased. This has been backed by survey data from one group (Pakistani Muslim’s) who generally put more importance on higher education rather than enlistment.

Army Ranks and Diversity

The last variation to be discussed in relation to race in the British army is the differences in representation between senior and enlisted ranks. In 2018 the MOD confirmed at the time they didn’t have a single BAME individual in the most senior three ranks of the British Army, as of 2021 this still seems to be the situation. Furthermore, as of April 2021 only 2.7% of BAME personnel accounted for Regular Officers. The lack of diversity in the senior racks is most likely contributing to both internal and external issues relating to diversity.[13]

The majority of the time the general public interacts with the British army is through media, this is even more common for BAME individuals considering they often lack family tradition/ties to the British army. This links to the lack of senior officials because they are the individuals who are often discussing issues of race and the army as well as talking in recruitments campaigns. The Ministry of Defence MOD has failed to recognise that a contributing factor in the lack of recruitment success is the continued perception of the British Army as being an old boys club.

Finally, according to a review in military environments there have been suggestions that the environment within the army often turns BAME personnel against one another. This has led to senior BAME personnel being seen to be harsher to their BAME subordinates to avoid accusations of favouritism or positive discrimination. This has been seen as a barrier to enhancing organisational diversity as it reduces the chance of senior mentorship, or an open environment to make complaints.[14]

Black Lives Matter movement

The murder of George Floyd by police officers in May of 2020 forced the Black Lives Matter movement to the forefront of discussions surrounding institutionalised racism. The colonial history of the British Army and its majority white workforce has led it to be a target for critique. The Black Lives Matter protests have been proceeded by a number of British Soldiers speaking publicly about their experiences of racism and discrimination during their service, they have highlighted issues with individuals uttering comments such as ‘people like you’ and ‘you people from the colonies’ which clearly seems to be an issue for BAME commonwealth servicemen. In addition, institutional and cultural failures have been raised. The same soldier who received the previous comments said that there is a “lip service and tick-box exercise with little or no consolidated effort to root out the underlying issues causing some of the most blatant offenders”. Another solider said that there is a ‘deep-rooted culture’ which is forced to change from the top, suggesting that there are underlying issues that need to be fixed prior to individuals joining regiments.

In Decolonizing the British Army, Anthony King discusses the issues that foreign commonwealth soldiers in particular experience which is a result of the culture within the army. King explains that due to the majority of the British army being ‘under 25 years of age’ they tend to be more ‘sensitive to the risk of exclusion’. As a result, their insecurity leads them to conform to the cultural norms and as a result those who are even slightly different are often excluded. This is relevant to the project as commonwealth individuals are firstly, likely to form groups as the pressure of the barracks leads groups to form around cultural identities. This is further fuelled by the fact that they are not British and so cannot bond on ‘indigenous cultural resources’ such as football teams or television programmes. Race can then play an additional role becoming an ‘ethnic boundary marker. This situation is highlighted when white commonwealth individuals find it easier to integrate into army life due to their common linguistic and cultural commonalities with British white soldiers.[15]

Discuss failure to produce an effective study, outdated information/accessibility of primary source data surrounding this issue (250)

Discussing topics such as race, diversity, representation, and discrimination in relation to the British army over the last thirty years has posed a challenge. Despite their being a plethora of insightful research into these topics, they are often outdated. The most useful academic literature I discovered during this project was published before 2015, which although insightful, lacked up-to-date statistics as well as awareness of the socio-political climate of the last 5 years. This lack of research and publication surrounding the army’s attempts to increase diversity recently often posed a challenge when discussing issues.

As a result of the lack of up-to-date research I sought to replicate Asifa Hussain’s 2003 survey into the opinions of Black British individuals’ perspectives of the British army. Despite this, my responses where limited and data lacked depth and as a result, I decided not to include this in my research project.

Another difficulty in providing evidence to support arguments is the culture of silence within the army. Few soldiers although this is changing are willing to discuss difficulties experienced during their time in the army due to fear of barriers whilst still enlisted or the backlash from other veterans and the military community.

An evaluation

To summarise the discussion in this research project, the 1990s was the beginning of a change in both the demographic and culture of the British army. The government wide evaluation of institutionalised racism led to the Strategic Defence Review, the most important literature in the last 30 years surrounding diversity and the British Army. Despite this, the SDR has not completely solved the lack of diversity or representation in the British Army. Arguably it has held it back, this is because a long time the British Army focused on numbers, most significantly the ratio between BAME soldiers in the army and UK population. The focus on this issue contributed to a lack of effort to tackle deeper rooted issues.

These issues are more nuanced and cannot be applied to every BAME individual or all the groups that make up the BAME military community. This includes the alienation of Islamic individuals, Foreign/Commonwealth individuals as well as a lack of representation within the most senior ranks of the army.

Importance in the broader perspective for the British Army, Country and the world

According to the MOD the armies’ primary functions are[16]:

- to ‘Protect the UK’

- ‘Prevent Conflict’, for example working with partner nations in Iraq and Afghanistan to deliver training

- ‘Deal with Disaster’, both at home and overseas (flooding, pandemic)

To successfully conduct these roles in the professional manner it is essential that the British army increases its diversity as well as external perceptions of its approach to race. Whilst working with foreign nations those who come from diverse backgrounds are often highly successful in forming relationships and bonds with foreign nationals, ensuring teamwork and co-operation. Furthermore, the British Army is increasingly working within the UK; helping during floods and currently with the Covid-19 Pandemic. To work within the ethnic minority communities in the UK, who are often at most risk it is essential to be culturally sensitive and understanding of all backgrounds and differences.

Future predictions

The first steps to solving the issues surrounding diversity in the British army have been done. The head of the armed forces Admiral Tony Radakin was quoted at the beginning of this project discussing these. The British Army has begun to recognise the impact that its colonial legacy has had on both civilian and military individuals. To be successful going forward they must tackle the deeply rooted cultural norms within the historical institution that often lead to BAME person leaving the army, in combination with mentoring schemes from senior officials this could contribute to an increased diversity within the most senior ranks of the army. Furthermore, schemes setup to hire higher educated BAME civilians would contribute to greater representation within commissioned officers.

Closing statements.

The British army has made great strides since the first formation of the colonial regiments during the reign of the British Empire, and it has made significant improvements since the release of the 1998 Strategic Defence Review. Despite this, if it hopes to be a combat force of the future it will take more than high tech weapons, it must come to understand that often conflicts today require soft skills such as diplomacy and cultural sensitivity both which don’t depend on but do improve with ethnic diversity.

Bibliography

Basham, V. M., 2009. Harnessing Social Diversity in the British Armed Forces: The Limitations of ‘Management’ Approaches. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 47(4), pp. 411-429.

blackhistorymonth.org.uk, 2015. For whom the bells toll. [Online]

Available at: https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/bhm-heroes/for-whom-the-bells-toll/ [Accessed 25 12 2021].

DiversityUK, N/A. Diversity in the UK. [Online]

Available at: https://diversityuk.org/diversity-in-the-uk/ [Accessed 28 12 2021].

Forces.net, 2021. Army officer’s inspirational advice to tackle racism. [Online]

Available at: https://www.forces.net/civvy-street/army-officers-inspirational-advice-tackle-racism [Accessed 4 1 2022].

Greene, D. B., 2016. A study of the British Army: white, male and little diversity. [Online]

Available at: https://www.lse.ac.uk/News/Research-Highlights/Society-media-and-science/British-Army [Accessed 20 November 2021].

Hussain , A. M. & Ishaq, M., 2014. Advancing the equality and diversity agenda in armed forces: global perspectives. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 34(7), pp. 598-613.

Hussain, A., 2003. Careers in the British Armed Forces: A Black African Caribbean Viewpoint. Journal of Black Studies, 33(3), pp. 312-334.

King, A., 2021. Decolonizing the British Army: a preliminary response. International Affairs, 97(2), pp. 443-461.

Mason, D. & Dandeker, C., 2001. The British Armed Services and the Participation of Minority Ethnic Communities: From Equal Opportunities to Diversity?. The Sociological Review, 49(2), pp. 219-235.

Mason, D. & Dandeker, C., 2009. Evolving UK Policy on Diversity in the Armed Services: Multiculturalism and its Discontents. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics , 47(4), pp. 393-410.

Ministry of Defence, QinetiQ, Birmingham University, BAE Systems, Napier University, 2020. TIN 2.101 Defence Inclusivity Phase 2: The Lived Experience Final Report, N/A: BAE Systems.

Ministry of Defence, 2019. Armed forces workforce. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-2018 [Accessed 25 November 2021].

Ministry of Defence, 2021. UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 1 April 2021. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-2021/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-1-april-2021 [Accessed 25 12 2021].

Ministry Of Defence, 2020. What we do. [Online]

Available at: https://www.army.mod.uk/what-we-do/ [Accessed 29 12 2021].

Office for National Statistics, 2018. Population of England and Wales. [Online]

Available at: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/latest [Accessed 25 November 2021].

Office for National Statistics, 2021. Population Estimates. [Online]

Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates [Accessed 2 1 2022].

Quinn, B., 2020. ‘People like you’ still uttered: BAME armed forces personnel on racism in services. [Online]

Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jan/07/people-like-you-still-uttered-bame-armed-forces-personnel-on-racism-in-services [Accessed 2 1 2022].

Renfrew, B., 2020. Britain’s Black Regiments: Fighting for Empire and Equality. 1 ed. Cheltenam: The History Press.

Sabbagh, D., 2021. British military must embrace diversity after scandals, says new chief. [Online]

Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/dec/07/british-military-must-embrace-diversity-after-scandals-says-new-chief

[Accessed 1 1 2022].

Sion, L., 2016. Ethnic minorities and brothers in arms: competition and homophily in the military. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(14), pp. 2489-2507.

[1] Sabbagh, D., 2021. British military must embrace diversity after scandals, says new chief. [Online]

Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/dec/07/british-military-must-embrace-diversity-after-scandals-says-new-chief [Accessed 1 1 2022].

[2] blackhistorymonth.org.uk, 2015. For whom the bells toll. [Online]

Available at: https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/bhm-heroes/for-whom-the-bells-toll/ [Accessed 25 12 2021].

[3] DiversityUK, N/A. Diversity in the UK. [Online]

Available at: https://diversityuk.org/diversity-in-the-uk/ [Accessed 28 12 2021].

[4] Ministry of Defence (1998) The Strategic Defence Review. p58. [Online]

Available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/RP98-91/RP98-91.pdf

[5] Mason, D. & Dandeker, C., 2009. Evolving UK Policy on Diversity in the Armed Services: Multiculturalism and its Discontents. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics , 47(4), pp. 393-410. [Accessed 28 12 2021].

[6] Mason, D. & Dandeker, C., 2001. The British Armed Services and the Participation of Minority Ethnic Communities: From Equal Opportunities to Diversity?. The Sociological Review, 49(2), pp. 219-235.

[7] Ministry of Defence, 2021. UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 1 April 2021. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-2021/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-1-april-2021 [Accessed 25 12 2021].

[8] Greene, D. B., 2016. A study of the British Army: white, male and little diversity. [Online]

Available at: https://www.lse.ac.uk/News/Research-Highlights/Society-media-and-science/British-Army [Accessed 20 November 2021].

[9] King, A., 2021. Decolonizing the British Army: a preliminary response. International Affairs, 97(2), p. 460

[10] Hussain, A., 2003. Careers in the British Armed Forces: A Black African Caribbean Viewpoint. Journal of Black Studies, 33(3), p.317

[11] Ministry of Defence, 2021. UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 1 April 2021. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-2021/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-1-april-2021 [Accessed 25 12 2021].

[12] Mason, D. & Dandeker, C., 2009. Evolving UK Policy on Diversity in the Armed Services: Multiculturalism and its Discontents. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics , 47(4), p.401

[13] Ministry of Defence, 2021. UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 1 April 2021. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-2021/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-1-april-2021 [Accessed 25 12 2021].

[14] Ministry of Defence, QinetiQ, Birmingham University, BAE Systems, Napier University, 2020. TIN 2.101 Defence Inclusivity Phase 2: The Lived Experience Final Report, N/A: BAE Systems. P.64

[15] King, A., 2021. Decolonizing the British Army: a preliminary response. International Affairs, 97(2), pp. 443-461.

[16] Ministry Of Defence, 2020. What we do. [Online]

Available at: https://www.army.mod.uk/what-we-do/ [Accessed 29 12 2021].