An attempt to decipher how Special Air Service misconduct is systematic, and how it can be used or removed.

By Felix Smart

Introduction – Who are the Special Air Service?

The British Armed Forces consists of many components across hundreds and thousands of personnel across the United Kingdom and wider world, yet the supposedly most covert units – Special Forces (SF) – get the most coverage in both the media and popular culture.[1] This constant cultural subjugation of highly trained elite warriors has created a general public perception that simply the status of special forces justifies some of the horrific acts of violence conducted in the field under the pretext of national security.[2] Simultaneously, we have witnessed a rise in internal “elevation” of special forces which has led to a policy-level justification of morally ambiguous special forces action.[3]

By combining these ideas, an apparent trend appears: a highly positive public perception combined with unrestricted rules of engagement (RoE) creates a defence mechanism of subconscious public and political authorisation even in light of evidence contradicting the legality of special forces actions. I have dubbed this term ‘mythos shielding’, the legal shield forged in myth that shrouds or excuses illegal action.

This webpage will attempt to explain the phenomenon of ‘mythos shielding’ in relation the Special Air Service (SAS), and seeks to answer question relating to SAS ethics, conduct and culture – both within the military and the public at large.

…

A Brief and Bloody History of the SAS

For this argument to have any serious standing, mythos shielding must be grounded in the direct history of the SAS and special forces literature. SAS literature is widely available, and this history will not be comprehensive, but it is important for the context of this webpage.

The Special Air Service was a Regiment founded by Commando-Trained Scots Guard David Stirling, an officer of the British Army who requested the creation of a small, highly elite unit that could infiltrate and sabotage Nazi operations in Africa.[4] The subsequent successes of sabotage missions of Rommel’s tanks in Africa, as well as disruption of Luftwaffe operations were highly successful.[5] Similar operations took place in Sicily and Italy, with amphibious raids and tactical infiltrations.[6] These operations were limited to 1944, which saw the first wide scale usage of commando units, rendering special forces a permanent feature of modern warfare.[7]

However, for the British, the government policy of army reduction led to a (brief) disbanding of the SAS from 1945-1947. The reignition of conflict with Western and Soviet Russian aggression led to the War Office suggesting that the prior success of clandestine operations should lead to permanent establishment of the SAS.[8] Historian Grob-Fitzgibbon argues that from the early 1950s, the SAS was a state tool used to project British power in sinister ways, conducting lethal action outside the realms of conventional warfare in communist and post-colonial states.[9] For the SAS, this translated into bloody excursions into Malaya from 1948-1960, in which the successes of the regiment was limited of Malaya was limited, with the SAS being able to claim only 108 combatants killed out of the 6,398 insurgents killed.[10] This did not render the SAS useless, as the importance of intelligence collected by special forces in Malaya not only solidified and justified the unit’s existence in the British Army, but also saw its refinement into two units – to be kept as an “ elite force in a scaled down regular army”.[11][12]

This in practice translated to a policy shift for SAS operations, to being primarily intelligence gathering and rapid response in the post-Malayan Insurgency landscape.[13] Special Air Service deployments across multiple theatres such as Yemen, Aden and Oman were structured around highly specialised, small, and self-sustaining units throughout the 1960s and 1970s.[14]

Yet of the most important developments in the history of the SAS was the British Governments open acknowledgement and authorisation of SAS reconnaissance and intelligence inside Northern Ireland from January 1976.[15] SAS usage coincided with legal expansions on the jailing of political extremism and gave United Kingdom Special Forces (UKSF) the legal justification for the creation of “psudo-gangs” to cause “[demoralisation] or to terrorise [communities]”.[16]

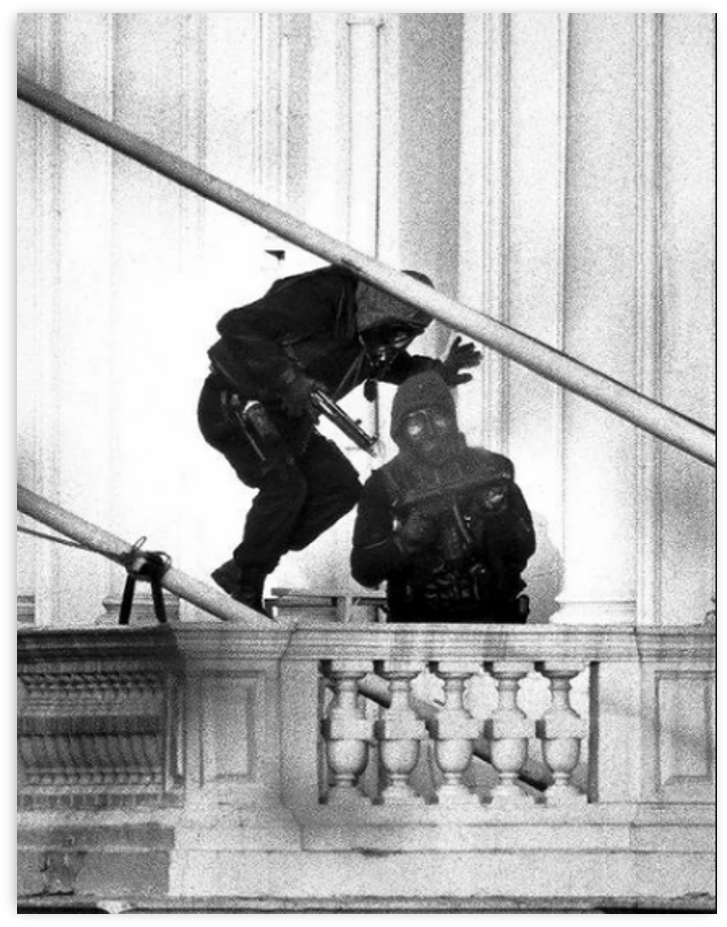

The Key turning point for public perception of the Special Air Service was the dramatic broadcasting of the 1980 Iranian Embassy Siege, which involved the use of the SAS to end the hostage crisis by eliminating the six armed hostage takers.[17] Codenamed “Operation Nimrod”, the immense success of the operation was deliberately used as a show of force by prime minister Margaret Thatcher, making the SAS a “national treasure”, with the regiment garnering favour with the public and policymakers alike.

“Another of [Margaret Thatcher’s] achievements was to bring the SAS out of the shadows. At the siege we had smoke generators ready to be initiated as the assault went in. They would have put a smokescreen down and blocked the view of the world’s media. Word came down from Mrs Thatcher via Cobra: ‘‘don’t initiate the smoke generators.” She wanted the whole assault on the TV screens to send a message to the world’s terrorists.”

– Former SAS operative Pete Winner.[18]

With the fall of the Soviet Union, the UK government narrowed its focus to combatting terrorism on a global scale.[19] Combined with defence budget cuts in the 1990s, the utilisation and overreliance on smaller, elite units such as the SAS were the perfect tool for policy makers to deal with asymmetrical threats in a cost-effective way.[20] Representing a further concentration of SAS power, budget cuts meant that personnel were highly well equipped, trained and had policy tailored towards their operations.[21] The SAS were utilised by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) on reconnaissance, distraction and search-and-destroy missions of Iraqi missile sites.[22]

…

Conduct and usage of the Special Air Service in Modern Warfare

Once we understand the evolution of British Special Forces, it is important to understand the discrepancies between Special Forces (SF) and the conventional military. Dean-Peter Baker et. al. define that the parameters of SF in six characteristics: time-sensitivity (of the mission), a reliance on clandestine activities, inherent covertness, operationally small footprints, political discretion, and a higher degree of risk.[23] In practical terms this translates to what Alastair Finlan describes as a “different kind of soldier” who can operate covertly and overtly within civil society and the world at large.[24]

Seeing as Special Forces operate in significantly harsher environments, the need for autonomy and limited operational oversight is paramount to the existence and purpose of units such as the SAS in the first place. In ethical terms, this means that conduct is advisory, and actions taken within the field are left to each individual operative within a team who will have to make split second decisions of their own volition.[25] Extreme Discipline and morality are necessary requirements of SF operations to ensure that “non-doctrinal solutions” do not amount to misconduct.[26]

Not only is the operational environment a risk to the individual SAS operatives on the ground, but the geopolitical environment that justifies the regiments existence is threatened by budget cuts and extensive oversight. Arguments presented by historians such as David Thomas argue that from its origins in 1941, “the various raiding forces in the Middle East, including the SAS, [did not make] a decisive contribution to British victory”.[27] Counter-arguments by Alistair Finlan describe the same operations in the African deserts as a “highly potent” and effective combination.[28] The contested nature of the actual effectiveness of SAS operations can make the pool of literature wide and varied. SAS histories therefore offer themselves as the ‘definitive history’, overshadowing peace achievements of Britain, rendering the UKs power to the shadowy warriors of the Special Air Service – strengthening the mythos shielding of the regiment.[29]

SAS officers and policymakers have often also taken the line that their actions have been significant, despite contradicting evidence. The appointment of Peter De La Billière as director of the SAS from 1978-1982 led to the cultivation of a close relationship between Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the Special Air Service, and was a critical component to the boosting of the SAS within policy making and deployment initiatives.[30] One such operation capitalised on was the SAS’s pivotal role in the Falklands War, which in turn De La Billière used to justify his expansive use of the SAS in destroying Scud Missiles in the Gulf War.[31]

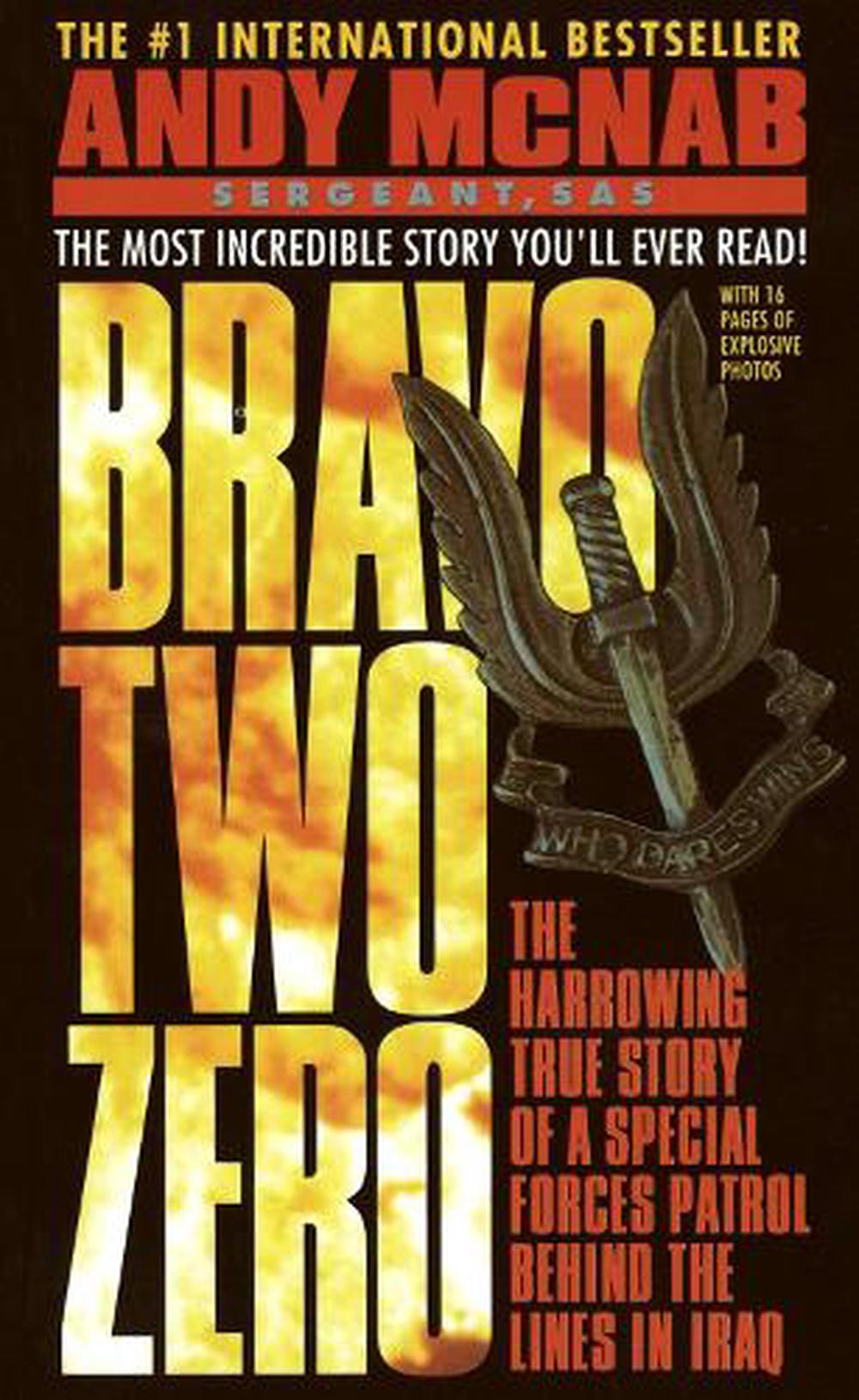

The Gulf War was the proving ground for a special-forces oriented doctrine for Britain, In part due to a severe fluctuation in results of operations.[32] A stressing of the mission criticality of the SAS was highly successful for the funding and favourability of the SAS, and was only possible due to relations between Thatcher, De La Billière and the Ministry of Defense.[33] This favourability was slightly undermined with incidents such as the infamous “Bravo Two Zero” – which saw an eight-man SAS Patrol compromised and almost completely wiped out by Iraqi forces (three men were killed whilst four were captured and tortured) whist attempting to destroy Scud Missile Launchers in Northern Iraq.[34]

Due to the inherent nature of Special Forces confronting life-threatening decisions with only a few seconds to act, it can be understood that accidents, tragedies, and fatalities can occur. David Stirling expressed the need for both “the pursuit of excellence” and “self-discipline” as fundamental pillars of how the SAS can best avoid unnecessary killing on the field.[35]

However, the issue I aim to address is when mistakes become systemic, and unlawful actions replace the Special Air Service’s origins of ‘the pursuit of excellence’. Journalist and historian Max Hastings argues that misconduct is embedded within the unit, and special forces on a wider level – recalling an interview in which a former SAS member actively preached for the unit’s integrity yet recalled an account of rape during the Italian campaigns of World War II.[36]

“[The SAS operative] told [Hastings] of one episode during a long, hot firefight on an Italian hillside in 1943, when he shared a slit-trench with a former professional boxer turned commando. That pugilist spotted a cluster of women sheltering under a bridge 50 yards away. He sprang out of the trench, raced across the hillside amid a storm of German fire, and, in the words of my interviewee, “had one of the women and was back inside three minutes.”

– Anonymous

We see how the media and operatives depict horrific atrocities committed by SAS members: with both citing “rogue” SAS members or units, rather than attacking the regiment as a whole.[37] The ongoing Afghanistan Inquiries reflect that a combination of a society obsessed with violence and an internal reluctancy by government and military official, the media and the wider citizenry to stand up to the SAS make the regiments “mythos shielding” highly effective.

…

The SAS in Afghanistan

The Special Air Service’s mission in Afghanistan has been long and varied. Starting on October 7th, 2001, UK prime minister Tony Blair announced that British troops would be involved in the NATO-led “Operation Enduring Freedom” and made up the second largest contingent in the campaign.[38] Alongside the deployment of conventional forces, the SAS were deployed from 2001 to hunt down the Taliban across Afghanistan, as well as deployment in Iraq in the Global War on Terror (GWOT).[39]

The mandate of the United Kingdom during the war in Afghanistan saw a shrinking of conventional forces due to budgetary constraints and reduced personnel.[40] However, this reflects an expansion in special forces, including the creation of Special Operations Forces (SOF), a Special Reconnaissance Regiment (SRR), a Joint special Forces Support Group (JSFSG) and unification of the SAS and Special Boat Service (SBS) under UKSF.[41]

However, from the outset of the Afghanistan deployment the command and control of the SAS was drastically different to that of regular forces, or even from other special forces. The SAS was immediately deployed following the September 11 attacks, being used to assault a Taliban and Al-Qaeda cave complex near Kandahar, killing eighteen combatants and taking forty as prisoners.[42]

The activities of the SAS and other SOFs in early Afghanistan are believed to be similar in nature to the Kandahar cave assault, however due to their sensitive nature as classified documents, we simply do not know what special forces did in the early war.[43] This is because of the fallout of the Bravo-Two-Zero incident, in which a plethora of books surfaced about the ‘failed’ SAS operation.

However, Bravo-Two Zero proved to be very useful for both individuals involved and the regiment. The shaping of events as a ‘daring escape’ proved to be very profitable off the back of a catastrophic SAS failure, as is seen with the infamous book “Bravo Two-Zero” by Andy McNab.[44] In conjunction with MoD vetting, the book fuelled the mythos of the SAS – adding to the myth, awe and exploits of the world’s most elite unit.[45] This however, was not a tool the SAS had available in Afghanistan, and as such failures would emerge through news reports and leaked or public documents, with limited SAS input on events.

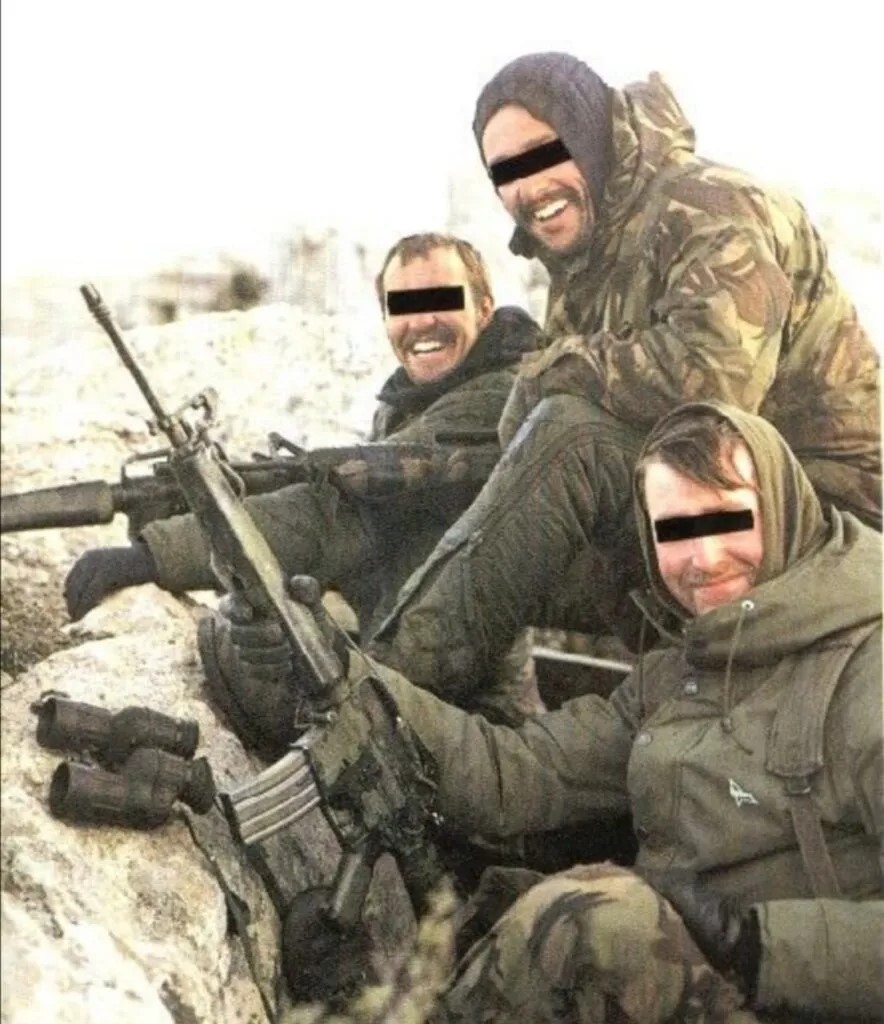

Throughout the course of the Afghanistan war, Special Forces were used as both training instructors and reconnaissance units, an estimated 200 of which heralded from the SAS.[46] Even after the wars official end in 2015, SAS operatives continued to operate, with their most recent use as protecting the array of C-17 Globetrotters withdrawing coalition forces from Afghanistan in September 2021.[47]

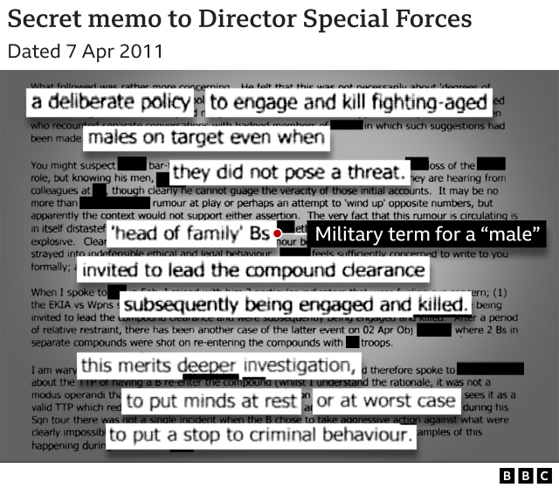

The most highly controversial conduct of the SAS in Afghanistan involve allegations of war crimes, primarily revolving around summary executions of prisoners of war.[48] A BBC Panorama investigation accuses one SAS unit of killing fifty-four people in one six-month tour in Helmand between 2010 and 2011.[49] The SAS unit was sent out on “kill or capture” raids of suspected Taliban leaders, with the vast majority of missions resulting in lethal force applied to detained citizens doing escorted sweeps of their homes.[50] During these missions. the SAS is also accused of setting attack dogs on Afghani children whilst they slept and one patrol are accused of shooting farmers on sight before arrests could be made.[51]

Documentation reviewed by the charity Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) highlights that a potent mix of unreliable intelligence and preference of kill over capture resulted in a systemic violation of the rules of engagement.[52] This led to the repeated execution of civilians unconnected to the Taliban, which was allegedly masked by the planting of weapons on innocent bodies under the guise of “Operation Cestro”.[53]

The preference for kill over capture is not new for the SAS, as during the Malayan Emergency, an SAS unit known as “The Malayan Scouts” adopted a similar policy against the Chinese insurgency. Captain John Woodhouse noted that their success mattered not about the numbers saved, but about the number of MRLA guerilla fighters killed.[54] This mentality, therefore, can be presumed to not be exclusive to Afghanistan – but to the regiment as a whole.

Yet in Malaya, Captain Woodhouse himself was “appalled” by the lack of discipline and aggression on and off missions, noting how the rest of the British Army saw them as “badly behaved, badly turned out [and] irresponsible”.[55] This further amplifies a necessity to review the systemic unlawful doctrine inside the SAS once off-duty actions are considered. On the 11th of December 2023, Armed police allegedly arrested two SAS soldiers for running a drug ring from an isolated farm within Hereford, harking back to Captain Woodhouse’s judgement of poor discipline off duty within the SAS.[56] However the mythos shielding of the SAS is on full display, as the two soldiers were bailed (presumably by the regiment or the MoD) on suspicion of class A drug offences.[57]

The ’cult of the SAS’ reflects the fact that mythos shielding is a powerful tool both in terms of public perception and internal alliance. BBC Panorama investigations later revealed that General Gwyn Jenkins, the United Kingdom’s second most senior commander of the armed forces, purposefully filed the initial reports of extrajudicial killings away into a locked safe.[58]

This intimate relationship between senior UKSF command and the Special Air Service has been established since the beginnings of the Iraq and Afghanistan operations, one notable feature which shrouds the SAS in a legal and reputational cloak is the command structure under which they operate. SAS units would relay mission information directly to “Zero Alpha” at London headquarters, reflecting a major reduction in the chain of command.[59] As a result, SAS misconduct travels straight up to high command, where any disclosure of its activity reflects their failings – the same structure that enabled General Jenkins to bury documentation on SAS war crimes.

…

Tackling Mythos Shielding – The Brereton Report

The Afghanistan Inquiry has shown that SAS mythos shielding is protected both internally and externally, with the world – particularly the western world – still being in ‘awe’ of the extreme capabilities of special forces.

However, one such SAS unit that has had their mythos shield penetrated is that of the Australian Special Air Service Regiment (SASR) – a group closely associated and designed like the British SAS, being a commonwealth country themselves. The Brereton Report reflects Australian efforts to combat special forces misconduct, and as such I believe it is critical to judging, understanding, and combatting mythos shielding.

The Brereton Report was a culmination of four years of painstaking effort by Major General Paul Brereton, uncovering very similar findings to BBC Panorama: the murder of 39 Afghanis in 29 incidents, with two reports of “cruel treatment”.[60] The Report outlines four specific methodologies utilised by the SASR: ‘Body Count Competitions’ using legitimate target lists, direct engagement of hostiles, clearance operations with minimal regard for life, and cover-ups.[61]

In comparison to the British SAS scenario, there is very little difference besides the level of investigation that is undergoing, and the reputation of the units involved. One key difference is that the Brereton Report explicitly deals with internal loyalty: calling on responsibility to be bored by “those who embraced or fostered the ‘warrior culture’” and those “in misconceived loyalty to their Regiment … have not been prepared to call out criminal conduct”.[62]

…

The Special Air Service: Conclusions on the Use of Mythos Shielding

It is with both the Brereton report and the history of the SAS in mind that we must decide on the fate of SAS mythos shielding, and I believe that there are two distinct directions that must be considered in order for special forces operations to evolve: we reform, or we accept.

To reform would mean that the Brereton Report exemplify what must be done to the British SAS for the sake of the Regiment, MoD, and wider British Army. To attempt reform would mean to destroy the ‘mythos’, to rebuke the sentiment that special forces and SOF are not indestructible, infallible and above the law. It would, in essence, mean acknowledging these soldiers are human, and perhaps the SAS could once again return to the shadows, or stay in the limelight – allowing new special forces to protect the country in a ‘legal’ and ‘ethical’ manner. ‘Who dares wins’ would represent the integrity Captain Woodhouse demanded in Malaya once again. Mythos Shielding would cease, and the SAS would be an admired and respected force for good.

To accept would not necessarily be an evolution, but a tacit acknowledgement that there is a gruesome necessity for a select group of individuals to commit catastrophic and ruthless violence for the sake of ‘national security’. This path would render the SAS a highly effective fear tactic, firmly secured behind a history of myth that ‘who dares wins’ means that ‘none dare question’. The SAS would forever live the days of the Iranian embassy siege, invoking imagery of an elite national execution squad to eliminate the foes of Britain at any cost. Mythos Shielding would be weaponised, the SAS would now be a legendary spectre of death – fighting terror with fear.

Bibliography

AOAV, ‘Independent Inquiry relating to Afghanistan: day 3’ (11 Oct 2023). Available at: https://aoav.org.uk/2023/independent-inquiry-relating-to-afghanistan-day-3/ [Accessed 08/01/2024].

AOAV, ‘Ops 1. UK Special Forces Operations: Afghanistan’ (16 May 2023). Available at: https://aoav.org.uk/2023/afghanistan-2/ [Accessed 07/01/2024].

Arbuthnott, G. et al. ‘Rogue SAS Afghanistan execution squad’ exposed by email trail’, The Sunday Times, 01 Aug 2023. Available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/rogue-sas-afghanistan-execution-squad-exposed-by-email-trail-7pg3dkdww [Accessed 23/11/2023].

Baker, D. et al. The Ethics of Special Ops: Raids, Recoveries, Reconnaissance and Rebels (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Davies, A. et al. ‘Chapter 4: Allied Special Operations Forces’, in A versatile force: The future of Australia’s special operations capability (Australian Strategic Policy Institute: Melbourne, 2014), pp. 19-22.

Faligot, R. ‘Special War in Ireland’, The Crane Bag, Vol. 4 (1980-1981), pp. 57-61.

Finlan, A. “The (Arrested) Development of UK Special Forces and the Global War on Terror”, Review of International Studies, Vol. 35. (2009), pp. 971-982.

Finlan, A. Special Forces, Terrorism and Strategy: Warfare by Other Means. (London: Routledge, 2008).

Gaynor, J. et al. ‘Inspector‐General Of The Australian Defence Force Afghanistan Inquiry Report’ (Melbourne, Commonwealth of Australia, 2020).

Grob-Fitzgibbon, B. ’Those Who Dared: A Reappraisal of Britain’s Special Air Service, 1950–80’, The International History Review, Vol. 37. (2015), pp. 540-564.

Hastings, M. ‘The UK is Way Too Besotted With its SAS’, The Washington Post, 4 Dec 2022. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/the-uk-is-way-too-besotted-with-its-sas/2022/12/04/d9876588-73b2-11ed-867c-8ec695e4afcd_story.html [Accessed 16/11/2023].

Joshi, S. “Assessing Britain’s Role in Afghanistan”, Asian Survey, Vol. 55. (2015), pp. 420-445.

King, A. ‘The Special Air Service and the Concentration of Military Power’, Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 35. (2009), pp. 646-666.

Knaus, C. ‘Key findings of the Brereton report into allegations of Australian war crimes in Afghanistan’, The Guardian, 19 November 2020. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/nov/19/key-findings-of-the-brereton-report-into-allegations-of-australian-war-crimes-in-afghanistan [Accessed 08/01/2024].

Leary, J. ‘Searching for a Role: The Special Air Service (SAS) Regiment in The Malayan Emergency’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol. 73. (1995), pp. 251-269.

National Army Museum, Iranian Embassy Siege. Available at: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/iranian-embassy-siege [Accessed 01/01/2024].

National Army Museum, Special Air Service. Available at: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/SAS [Accessed 01/01/2024].

Nicol, M. ‘Who Dares Sins? Armed police arrest two SAS soldiers as they smash ‘drugs ring run from isolated farm’ near Special Forces’ Hereford HQ after lengthy surveillance operation’, The Daily Mail, 11 Dec 2023. Available at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12852161/Armed-police-smash-suspected-drug-ring-involving-SAS-troops-two-servicemen-soldiers-wife-arrested-isolated-Herefordshire-farm.html [Accessed 08/01/2024].

O’Grady, H. et al. ‘Top general locked away evidence of SAS executions’, BBC News, 16 November 2023. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-67418001 [Accessed 08/01/2024].

O’Grady, H. et. al, “SAS unit repeatedly killed Afghan detainees, BBC finds.”, BBC (12 July 2022). Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-62083196 [Accessed 24/11/2023].

Panorama: SAS Death Squads Exposed: A British War Crime? BBC1, 12 July 2022, 21:00.

Ryan, N. ‘The SAS man who wouldn’t stay quiet’, The Irish Times, 23 March 2004. Available at: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/the-sas-man-who-wouldn-t-stay-quiet-1.1136564 [accessed 05/01/2024].

Thomas, D. ‘The Importance of Commando Operations in Modern Warfare 1939-82’, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 18. (1983), pp. 689-717.

Winner, P. ‘Thatcher and the SAS’, Prospects Magazine, 19 April 2013. Available at: https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/politics/50943/thatcher-and-the-sas [Accessed 01/01/2024].

[1] Finlan, A. “The (Arrested) Development of UK Special Forces and the Global War on Terror”, Review of International Studies, Vol. 35. (2009), p. 971.

[2] Ibid., p. 981.

[3] King, A. ‘The Special Air Service and the Concentration of Military Power’, Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 35. (2009), p. 651-652.

[4] Ibid., p. 651.

[5] Thomas, D. ‘The Importance of Commando Operations in Modern Warfare 1939-82’, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 18. (1983), p. 697.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Grob-Fitzgibbon, B. ’Those Who Dared: A Reappraisal of Britain’s Special Air Service, 1950–80’, The International History Review, Vol. 37. (2015), p. 542.

[9] Thomas, D. ‘The Importance of Commando Operations in Modern Warfare 1939-82’, p. 697.

[10] Grob-Fitzgibbon, B. ’Those Who Dared: A Reappraisal of Britain’s Special Air Service, 1950–80’, p. 545.

[11] Ibid., p. 545-546.

[12] Leary, J. ‘Searching for a Role: The Special Air Service (SAS) Regiment in The Malayan Emergency’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol. 73. (1995), p. 269.

[13] Grob-Fitzgibbon, B. ’Those Who Dared: A Reappraisal of Britain’s Special Air Service, 1950–80’, p. 551.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., p. 556.

[16] Faligot, R. ‘Special War in Ireland’, The Crane Bag, Vol. 4 (1980-1981), p. 59.

[17] National Army Museum, Iranian Embassy Siege. Available at: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/iranian-embassy-siege [Accessed 01/01/2024].

[18] Winner, P. ‘Thatcher and the SAS’, Prospects Magazine, 19 April 2013. Available at: https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/politics/50943/thatcher-and-the-sas [Accessed 01/01/2024].

[19]King, A. ‘The Special Air Service and the Concentration of Military Power’, p. 649.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid., p. 649-650.

[22] National Army Museum, Special Air Service. Available at: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/SAS [Accessed 01/01/2024].

[23] Baker, D. et al. The Ethics of Special Ops: Raids, Recoveries, Reconnaissance and Rebels (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), p. 8-9.

[24] Finlan, A. “The (Arrested) Development of UK Special Forces and the Global War on Terror”, Review of International Studies, Vol. 35. (2009), p. 971.

[25] Baker, D. et al. The Ethics of Special Ops:, p. 17.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Thomas, D. ‘The Importance of Commando Operations in Modern Warfare 1939-82’, p. 697.

[28] Finlan, A. Special Forces, Terrorism and Strategy: Warfare by Other Means. (London: Routledge, 2008), p. 11.

[29] Hastings, M. ‘The UK is Way Too Besotted With its SAS’, The Washington Post, 4 Dec 2022. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/the-uk-is-way-too-besotted-with-its-sas/2022/12/04/d9876588-73b2-11ed-867c-8ec695e4afcd_story.html [Accessed 16/11/2023].

[30] King, A. ‘The Special Air Service and the Concentration of Military Power’, p. 649-650.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid., p. 650.

[33] Ibid., p. 650-651.

[34] Ryan, N. ‘The SAS man who wouldn’t stay quiet’, The Irish Times, 23 March 2004. Available at: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/the-sas-man-who-wouldn-t-stay-quiet-1.1136564 [accessed 05/01/2024].

[35] Finlan, A. Special Forces, Terrorism and Strategy:, p. 58.

[36] Hastings, M. ‘The UK is Way Too Besotted With its SAS’.

[37] Arbuthnott, G. et al. ‘Rogue SAS Afghanistan execution squad’ exposed by email trail’, The Sunday Times, 01 Aug 2023. Available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/rogue-sas-afghanistan-execution-squad-exposed-by-email-trail-7pg3dkdww [Accessed 23/11/2023].

[38] Joshi, S. “Assessing Britain’s Role in Afghanistan”, Asian Survey, Vol. 55. (2015), p. 420 (pp. 420-445).

[39] National Army Museum, Special Air Service.

[40] Davies, A. et al. ‘Chapter 4: Allied Special Operations Forces’, in A versatile force: The future of Australia’s special operations capability (Australian Strategic Policy Institute: Melbourne, 2014) p. 21. (pp. 19-22)

[41] King, A. ‘The Special Air Service and the Concentration of Military Power’, p. 651

[42] Ibid., p. 659.

[43] Finlan, A. Special Forces, Terrorism and Strategy:, p. 123.

[44] Ryan, N. ‘The SAS man who wouldn’t stay quiet’.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Joshi, S. “Assessing Britain’s Role in Afghanistan”, Asian Survey, Vol. 55 (2015), p. 420 (pp. 420-445).

[47] AOAV, ‘Ops 1. UK Special Forces Operations: Afghanistan’ (16 May 2023). Available at: https://aoav.org.uk/2023/afghanistan-2/ [Accessed 07/01/2024].

[48] O’Grady, H. et. al, “SAS unit repeatedly killed Afghan detainees, BBC finds.”, BBC (12 July 2022). Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-62083196 [Accessed 24/11/2023].

[49] Ibid.

[50] Panorama: SAS Death Squads Exposed: A British War Crime? BBC1, 12 July 2022, 21:00.

[51] Ibid.

[52] AOAV, ‘Ops 1. UK Special Forces Operations: Afghanistan’ (16 May 2023). Available at: https://aoav.org.uk/2023/afghanistan-2/ [Accessed 07/01/2024].

[53] AOAV, ‘Independent Inquiry relating to Afghanistan: day 3’ (11 Oct 2023). Available at: https://aoav.org.uk/2023/independent-inquiry-relating-to-afghanistan-day-3/ [Accessed 08/01/2024].

[54] Leary, J. ‘Searching for a Role:’, p. 257.

[55] Grob-Fitzgibbon, B. ’Those Who Dared:’, p. 544.

[56] Nicol, M. ‘Who Dares Sins? Armed police arrest two SAS soldiers as they smash ‘drugs ring run from isolated farm’ near Special Forces’ Hereford HQ after lengthy surveillance operation’, The Daily Mail, 11 Dec 2023. Available at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12852161/Armed-police-smash-suspected-drug-ring-involving-SAS-troops-two-servicemen-soldiers-wife-arrested-isolated-Herefordshire-farm.html [Accessed 08/01/2024].

[57] Ibid.

[58] O’Grady, H. et al. ‘Top general locked away evidence of SAS executions’, BBC News, 16 November 2023. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-67418001 [Accessed 08/01/2024].

[59] King, A. ‘The Special Air Service and the Concentration of Military Power’, p. 659.

[60] Knaus, C. ‘Key findings of the Brereton report into allegations of Australian war crimes in Afghanistan’, The Guardian, 19 November 2020. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/nov/19/key-findings-of-the-brereton-report-into-allegations-of-australian-war-crimes-in-afghanistan [Accessed 08/01/2024].

[61]Gaynor, J. et al. ‘Inspector‐General Of The Australian Defence Force Afghanistan Inquiry Report’ (Melbourne, Commonwealth of Australia, 2020), p. 120.

[62] Ibid., p. 115.