The Purple Poppy a symbol of remembrance. ©thepurplepoppy.au

Unlike humans, animals do not have a choice whether they want to be at war. Animals do not give their lives; their lives are taken from them. They are the silent heroes and victims of war. British military history is dominated by the stories of soldiers and their heroic actions and sacrifices, but the stories of animals have been neglected. The contribution that military animals have made to Great Britain, in all wars has largely been forgotten. Despite the deaths of 484,000 horses during the First World War.[1] These animals have not been sufficiently recognised for what they have done, which was to preserve human life. It has been only recently that this contribution has been acknowledged by the government with the construction of the Animals at War Memorial in December 2004, which was crowdsourced by the public and officially opened by Anne, Princess Royal. The memorial was inscribed with several messages such as “They had no choice” and “From the Pigeon to the Elephant they all played a vital role in every region of the world in the cause of human freedom. Their contribution must never be forgotten”. This was the first stepping stone in the recognition of animals, in 2006 The purple poppy was created by the charity Animal Aid, to memorialise animals that had participated in conflicts. The purpose of this page is to recognise the contribution that military animals regardless of size and role from WW1 to the War on Terror and beyond have given to Great Britain despite having no choice in the affair.

Before the Great War:

Elizabeth Southerden Thompson, Lady Butler, ‘Scotland for Ever’, 1881, Leeds Art Gallery. ©ArtUK

The above image depicts the doomed charge of the Light Brigade into the ‘Valley of Death’, during the Crimean War, this charge was devastating, the brigade lost 40% of its men and 475 horses.[2] The primary animals that the British Army used before the First World War were a mixture of equine animals, such as Horses and Mules. Heavier Horses were used for offensive actions, Calvary would act as shock troops breaking enemy troop formations and pursuing routing troops. Mules were used for logistical purposes to transport men and material from one place to another, particularly in difficult terrain in countries such as Afghanistan and other colonies. Not all animals however were used for direct warfare others were simply there for moral purposes, such as regimental mascots. The practice of adopting Mascots in the British Army has been a long-standing tradition. One example is The Royal Welsh, who have adopted Goats as their mascots, the earliest recorded example dates to the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775, during the American War of Independence, when a wild goat strayed onto the battlefield and was said to have led the Royal Welsh Fusiliers colour party from the field,[3] ever since a goat has been their mascot. The purpose of Mascots was to strengthen unit morale and bring luck to its soldiers. The First World War was the first war of its scale that the world had seen. It spanned many continents with neither side gaining a significant advantage over the other, it was a bloody war of attrition, because of this many new animals were used by the army and many existing animals took on many different roles, to supplement manpower and the lack of mechanisation.

Horses and Mules, The Great War

1st Reserve Regiment of Calvary in training, Aldershot, 1914 © NAM 1974-10-174-115

At the beginning of the outbreak of the First World War, horses were used in the same way that they had been previously in the Napoleonic and Crimean Wars, through grand calvary charges. British Generals, many of whom were calvarymen clung to the idea of an ultimate breakthrough by Calvary.[4] These charges would be swiftly cut down by the immense firepower of machine guns. On the 24th of August 1914, men from the 9th Lancers and the 4th Dragoon Guards attempted a mass cavalry charge across an open plain at Audregnies, against a stalwart defence line of German rifles, machine guns and artillery. The British ranks were annihilated. As both sides entrenched themselves, the role of calvary was significantly diminished, the proportion of British Soldiers in cavalry regiments fell from 9% in 1914 to 1% by 1918.[5] This was a new war, one of stasis and stalemate, where men and horses in the hundreds would be lost for metres of muddy ground. Yet horses continued to carry out roles, both mounted and dismounted.

Scene at a British water-supply post on the Continent, 1916 © NAM. 2007-03-7-163

When WW1 began the British army possessed only 25,000 horses, by the middle of 1917 it had acquired 591,000 horses 213,000 mules and even 47,000 camels.[6] Due to the mass amount of ammunition, food and water being expended at the front, maintaining supply lines was crucial for battlefield success. Motor transport was virtually impossible as artillery had destroyed the roads and turned the environment into a muddy wasteland. The majority of these horses were under the ownership of the Army Service Corps which had the momentous task of supplying millions of men, with just horses and wagons. To illustrate this fact 4,500 tons of bread a month was required by the British Army by November 1918. [7]Horses were also used to tow ambulances to evacuatewounded men to field hospitals.

Ten horses for working howitzers, 1916 © NAM. 2007-03-7-9

“The war of 1914-18 was an artillery war: artillery was the battle-winner, artillery was what caused the greatest loss of life, the most dreadful wounds, and the deepest fear”[8]. Artillery was critical in the First World War from its uses on huge bombardments on the Somme to concentrated barrages used in bite-and-hold tactics. Guns needed to be moved into firing positions and a continued stream of artillery shells was required to sustain the artillery piece. Horses and mules formed the backbone of this logistical operation, they fueled the war at the front. The Royal Artillery took note of how essential horses and mules were, the requirements for the number of horses needed in an artillery division rose from 6,106 to 24,868. It was a tremendous effort for these horses to pull guns that sometimes weighed up to around 1.5 tonnes plus ammunition.

Fortunino Matania, ‘Goodbye, Old Man’, 1922 ©Flickr

Horses and Mules also fulfilled the function of being a companion to a soldier. The relationship between soldier and horse was complex but highly important in day-to-day life, the army encouraged men to care for and bond with their horses. It provided the soldier with a connection to the outside world, to escape the horrors of war, the soldier came to regard his horse as almost an extension of his own being.[9] The horse ‘Warrior’ was injured and lost many times, but always returned to his master General Jack Seely. Warrior was one of 4 horses to be awarded the Dickins medal. Memoirs from the Front, comment that the suffering of men they could get used to, but the suffering of horses they could not get over and that stayed with them a long time. Between 1914 and 1918 the success of the British War effort was heavily dependent on the horse.[10] Man and horse marched together into battle, as companions. No longer were there brave charges across open plains, instead an endless amount of animals and men pulling heavy loads, in the rain and mud, with the distant sounds of explosions accompanying them.

Horses in the 21st Century

Left, A Squadron from the 1st Life Guards, August 1914 © IWM Q 66190. Right, The Life Guards on Parade ©AFP

By 1917 over a million horses and mules were in service over, losing 1 horse for every 2 men.[11]As of 2022 it was reported by the media that there are just 492 horses in service.[12]Advancments in both mechanisation and weaponry have resulted in Horses becoming obsolete in warfare, and traditional calvary regiments have lost their mounts and now use armoured beasts to penetrate and spearhead attacks. Despite Tanks, IFVS and Motor vehicles replacing the horse and mule in the combat and support role, they still play a significant role in the British Army. In the army today, horses almost entirely fulfil a ceremonial role, with the exception of some being Mascots. Although warfighting is the primary role of the British army, some regiments have secondary roles. Equipped with Warrior and Scimitar armoured fighting vehicles, the HouseHold calvary still parade on Horseback and wear their 18th-century uniforms, donning both helmets and curries. They guard both Royal and military locations and are the centrepiece of Royal parades and functions alongside their footguard counterparts. The Kings Troop Royal Horse Artillery is one of the army’s only units that only carries out ceremonial duties. They perform gun salutes to mark the grand occasions of State, Royal birthdays and funerals and deploy to events nationally for the Royal Windsor horseshow, Royal Welsh Show and central London. They also represent the army abroad in nations such as the Netherlands and Canada.

The Kings Troop Royal Horse Artillery, 2023 ©BritishArmy

Pigeons

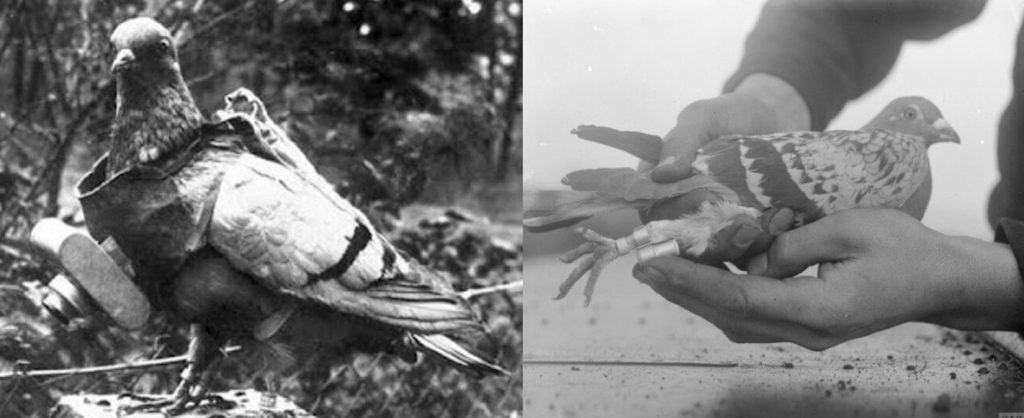

Left, Photographic Pigeon ©WW1Bridges. Right, A method of fixing a message to a homing pigeon for communication © IWM Q 18623

Although runners, despatch riders, telephones, radios and field telegraphs were the primary sources of communication on the battlefield and in the rear. They were not always reliable, as radio communication was still in its infancy and constant shelling led to the destruction of wires. Enemy fire also made it virtually suicidal for messengers both human and animal. As sad as it was pigeons were much easier to replace than a man and preserved human life. It was because of this that homing pigeons were relied upon to communicate critical information during battle, this was especially evident during the battle of the Somme. In the Somme, alone some 12,000 pigeons were used[13]. The role of Pigeons in warfare has fundamentally stayed the same throughout the thousands of years they have been used in warfare, travelling for up to speeds of 75mph, pigeons could cover 300 miles in one trip.[14]

However, pigeons were also used in an entirely new role, an espionage role. These pigeons flew with cameras, that took aerial photographs over enemy positions, which was critical in the planning and preparation of new offensives. Homing Pigeons were used in all 3 branches of the armed forces. This was ideal for the trenches of the First World War, as the frontline spanned hundreds of miles and the vast open sea. The British Army used pigeons in their tens of thousands during WW1 as messengers with an almost 95% success rate. The Signal Service numbered 20,000 birds with a roster of 380 experts by the end of the war.[15]

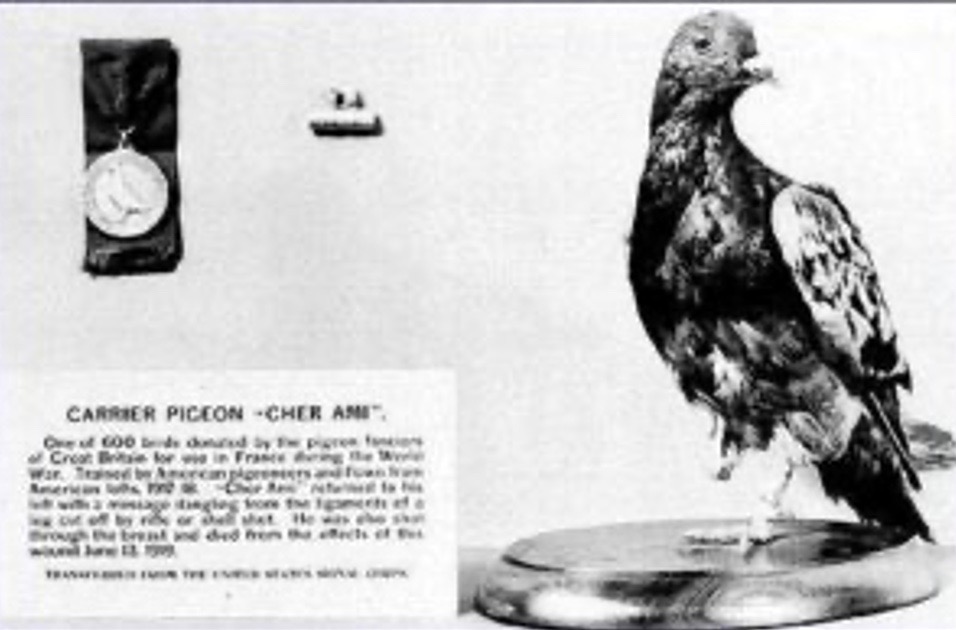

Cher Ami, ©Home of Heroes

Pigeons were especially brave animals and would complete their mission despite sustaining injuries. The most famous was Cher Ami, she is famous for delivering a message that saved the lives of 194 American soldiers, she did this despite being shot through the chest, blinded in one eye, with one leg hanging by a tendon.[16] Without a doubt, the use of pigeons contributed significantly to the war effort. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig mentioned the use of pigeons in his despatch on the 25th of December 1917. “The Carrier Pigeon Service has also been greatly developed during the present year, and has proved extremely valuable for conveying information from attacking units to the headquarters of their formations”.[17] Pigeons are now obsolete and no longer used by the British Army, due to innovations in more sophisticated radio and communication systems their legacy still does live on as brave and selfless animals who saved the lives of many men in both World Wars.

Dogs, The Great War

Left, A dog pulling a machine gun ©The Guardian Right, A dog handler reads a message brought by a messenger dog who has just swum across a canal ©Queens Ferry

“No animal has served man more nobly in war than the dog. Guarding outposts, detecting mines, racing messages through an inferno of gunfire-he acted out of love, not because he was made to”.[18] As man’s best friend, dogs have accompanied men into war for almost all of history. The First World War was the first war where dogs were used in an official sense and on a relatively large scale by both sides. 1400 Dogs were in service in the British Army during the Great War.[19] Their roles differed from running messages, medical dogs and sentries, they were very much on the frontline with their masters, many of whom possessed their very own gas masks. Dogs due to their speed and low profile made for excellent runners, one such case is Jack an Airedale whose battalion found themselves cut off and under enemy assault, but managed to make it through enemy lines to headquarters, the Sherwood foresters were saved, however, Jack succumbed to his wounds shortly after. It was astonishing he made it through with the wounds he sustained.

“A piece of shrapnel smashed his jaw, but he carried on, and another shell tore open his coat right down his back, and he kept on going. Finally, his forepaw was shattered, but he dragged his body for the last 3 kilometres.” [20] This was not just one circumstance, they took their duties very seriously and battled on despite being gassed or wounded.[21]

A soldier retrieving gauze from a British mercy dog ©ATI

Medical or Mercy dogs as they were known in the trenches, were dogs that assisted medics by locating wounded men whilst carrying a saddlebag with medical equipment and a drink to ease the suffering. They were trained to accompany the wounded soldier until a medic arrived or returned to the handler with a piece of equipment from the injured soldier. Dogs were able to detect life in soldiers who were previously overlooked by men as dead. A military surgeon praised these abilities of dogs saying “They always find a spark. It is purely a matter of their instinct, which is far more effective than man’s reasoning powers.”[22] It is not known how many lives these mercy dogs saved, but it can be estimated to be in the thousands.

A Scottish Regiment and their Ratter Dog in the trenches of WW1 ©AC

Dogs were also used unofficially by soldiers, these dogs normally being strays. This made the lives in the trenches more bearable they performed roles as guards, ratters, mascots and scouts, the dogs would comfort and provide companionship to the terrified men in the trenches. These dogs acted as early warning systems, as they could hear and smell better and would often act agitated and uneasy to warn the soldier.

Dogs in the 21st Century: Afghanistan and Iraq

Dog Handler in Afghanistan, ©Daily Mail

Dogs in the British Army today are still very much on the frontline, although they have taken on entirely new roles. The 1st military dog regiment was formed on the 26th of March 2010, to support the main brigade of troops on Operation Herrick.[23] The regiment consists of 299 regular soldiers and 384 working dogs as of 2015.[24] The armed forces were deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq alongside its NATO allies. The war on terror was fought against irregular cells of insurgents, who recognized they had a clear overmatch against them, in every aspect, despite this their morale was fanatical. Afghanistan has been in a constant state of war throughout its history and consequently, millions of mines and explosive material have been left there, forgotten. The UN estimates there are 10 million landmines active in Afghanistan[25]. To overcome this the insurgents used unconventional tactics such as ambushes, IEDs and suicide attacks. To mitigate this, British forces used dogs in varying roles, such as sniffer dogs to detect IEDS alongside EOD teams, and vehicle search dogs to locate explosives or drugs. IED strikes in Afghanistan constituted 49% of the deaths of British troops, which is 222 personnel.[26] Dog handlers and their canines were essential for operations against the Taliban, the story of LCpl Kenneth Rowe is an excellent example.

Lance Corporal Kenneth Rowe with Sasha, ©Forces Net

“As an Ammunition and Explosives Search Dog Handler, LCpl Rowe was an integral part of 2 PARA’s capability to conduct effective search operations. His job was to accompany patrols within the local area and to identify stocks of weapons, ammunition and explosives before they could be employed against ISAF forces or injure local people. This work inevitably placed both him and his dog in high risk situations on a regular basis. A fully integrated and popular member of the team, he had a pivotal role in support of the Company’s operations. On the evening of 24th July both LCpl Rowe and his dog, Sasha, lost their lives in a contact with the enemy whilst conducting a search operation.” [27] Major Chris Ham RAVC.

For her actions in Afghanistan, Sasha was posthumously awarded the PDSA Dickins Medal. “Sasha’s determination to search and push forward – despite gruelling conditions and relentless Taliban attacks – was a morale boost to the soldiers who entrusted their lives to her weapon-finding capability”[28]

Kuno, donning his medal ©PA

Lastly, dogs are used as force multipliers in the role of attack dogs, many of which are integrated into UKSF units that conduct raids against high-value targets in operations abroad, these dogs are trained to detect and track targets. Kuno a Belgian Malinois attached to the Special Boat Service, who despite a hail of bullets charged a Taliban Fighter and tackled him. Unfortunately, Kuno was shot in both of his hind legs, resulting in them being amputated, he was fitted with custom-made prosthetics to preserve his life. For his bravery, he was awarded the Dickens Medal, the highest military honour awarded to animals. Defense Secretary Ben Wallace said at the time “Without Kuno, the course of this operation could have been very different and it’s clear he saved the lives of British personnel that day”. [29]Dogs in the British army have shown their loyalty and value to the soldiers they have served alongside. Whether it was in the trenches of the Somme, or the poppy fields of Afghanistan, dogs have saved the lives of many men they are truly man’s best friend.

Mascots

Jimmy, Mascot of 1st Australian Auxiliary Hospital ©AWM H19084

The word ‘Mascot’ originates from the Provencal French word meaning ‘witch’ and signifies something that brings good luck. [30]Mascots have been an integral part of the British Army since the Napoleonic War. The First World War saw this tradition greatly expanded, as mascots brought their units a sense of national pride and morale. This made every unit unique as their Mascot animal was often tied to their regiment, for example, Madras Fusiliers had a tiger as their mascot, and The Royal Welsh a Billy goat. Units from Australia had Kangaroos and Wallabies, whereas units from Canada had black bears. Mascots were also used to alleviate the boredom, tension and impersonality of the war. After the war soldiers smuggled their mascots home, and since then it has become a regimental tradition. Some examples of unit mascots in the British Army during the First World War were as follows:

“Moses” an Egyptian donkey mascot of the New Zealand Army Service Company

Moses, Louvencourt 20th April 1918 ©NZGOV

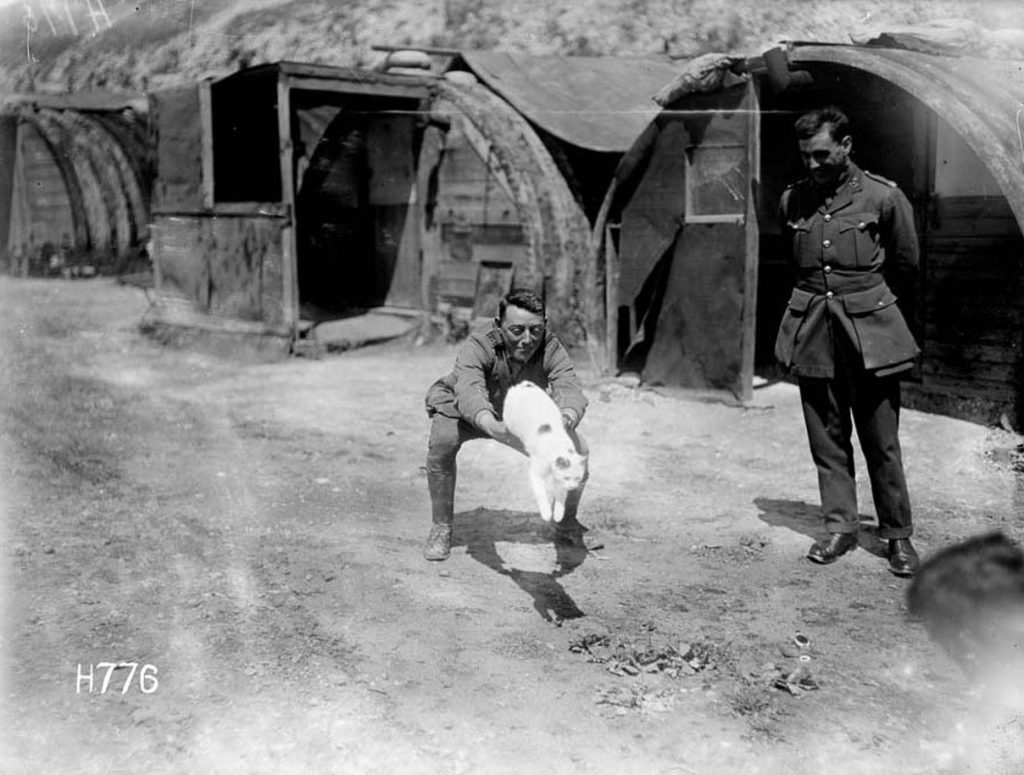

“Snowy” a tabby cat mascot of the New Zealand Tunnellers

Snowy, Dainville 16th July 1918 ©NZGOV

“Jackie” a baboon mascot of the 3rd South African Infantry Brigade

Commemorative Postcard with Pte Marr and Jackie ©The Observation Post

Mascots in the Present

Domhnall, Mascot of the Irish Guards ©Country Life

In the British army today, the army is divided into over 40 different regiments. Each regiment has its own Battle honours, mascots, customs and traditions that date back hundreds of years, which makes them all unique in their own right. History and traditions remain at the heart of the British Army identity. The Royal Fusiliers were awarded the hackle symbolising their defeat of the French at the Battle of St Lucia in 1778, however in 1829 King George ordered all infantry regiments to wear a hackle, but to distinguish the Fusiliers their plume was tipped with red.[31] The regimental Mascot is essential to a regiment’s culture as it makes them unique to others and the tradition dates back hundreds of years. An example of this is Mascots are almost always at the front of military parades; some even have ranks and their handler’s unique ranks. The mascot animal of choice usually comes from the area that the regiment is from, the Irish Guards’ mascot is an Irish Wolf Hound. Currently, the British army has 17 Mascots.

A video on the current Mascots of the British Army, ©British Army

Conclusion summary

Animals at War Memorial, London ©Wikipedia

Overall, this webpage has highlighted that military animals have changed extensively since the First World War. Previously military animals fulfilled primarily a support role in the form of logistics, medical and morale purposes. Regardless these animal’s contributions towards the war, were fundamental to the success of the Allied powers. Their role however has changed significantly since the great war. The role that animals now serve is largely a ceremonial role, except for dogs that perform combat and EOD roles that deploy alongside British soldiers abroad. This is because during the First World War animals carried out the functions of many technologies that weren’t invented at the time, as mechanisation improved these animals became less required, as machines replaced them. Horses were the powerhouse of the army, carrying equipment and ammunition, they were logistical trucks of old. We can see this largely in the role they play today, horses have turned into show animals, only ever to be used on parades and public events. Military animals both new and old have saved the lives of countless humans, both civilian and military. 75 of these animals have been awarded the Dickin Medal for their service to Great Britain. We must recognise the sacrifice and the service of these animals, as they had no choice whether to serve or not, yet they carry out their duties nonetheless.

A memorial of a war horse in London,©The Telegraph

Bibliography:

Anne kelley and Reply (2021). State Library Victoria Pigeon messengers of World War I. [online] Available at: https://blogs.slv.vic.gov.au/our-stories/pigeon-messengers-of-world-war-i/#easy-footnote-1-41021 [Accessed 1 Jan. 2024].

archives.the-monitor.org. (n.d.). Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor. [online] Available at: http://archives.the-monitor.org/index.php/publications/display?url=lm/1999/afghanistan#:~:text=For%20several%20years%2C%20the%20United [Accessed 3 Jan. 2024].

Baker, C. (n.d.). Carrier Pigeon Service. [online] The Long, Long Trail. Available at: https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/army/regiments-and-corps/the-corps-of-royal-engineers-in-the-first-world-war/carrier-pigeon-service/ [Accessed 1 Jan. 2024].

Baker, C. (n.d.). The Royal Artillery in the First World War. [online] The Long, Long Trail. Available at: https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/army/regiments-and-corps/the-royal-artillery-in-the-first-world-war/.

Baker, C. (n.d.). War Dogs in 1914-1918. [online] The Long, Long Trail. Available at: https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/war-dogs-in-1914-1918/ [Accessed 2 Jan. 2024].

Cooper, J. and Internet Archive (2000). Animals in war. [online] Internet Archive. London : Corgi. Available at: https://archive.org/details/animalsinwar0000coop/page/46/mode/2up?view=theater [Accessed 30 Dec. 2023].

Curator (2022). A Brief History of The Regimental Mascot. [online] Royal Welsh Museum. Available at: https://royalwelshmuseum.wales/a-brief-history-of-the-regimental-mascot/.

Dogs of war: How man’s best friend joined him at the front. (2014). BBC News. [online] 7 Aug. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-tayside-central-28681128 [Accessed 2 Jan. 2024].

Forces Network. (2014). Hero Army Dog Given Posthumous Award. [online] Available at: https://www.forces.net/services/army/hero-army-dog-given-posthumous-award [Accessed 3 Jan. 2024].

Gardiner, J. and Internet Archive (2006). The animals’ war : animals in wartime from the First World War to the present day. [online] Internet Archive. London : Portrait. Available at: https://archive.org/details/animalswaranimal0000gard/page/40/mode/2up?view=theater [Accessed 30 Dec. 2023].

Gladstone, H.S. and Smithsonian Libraries (1919). Birds and the war. [online] Internet Archive. [London, England] : Skeffington & Son. Available at: https://archive.org/details/birdswar00glad/page/2/mode/2up?view=theater [Accessed 1 Jan. 2024].

Gleadow, E. (2022). British Army still has more horses than tanks, even though beasts useless in war. [online] Daily Star. Available at: https://www.dailystar.co.uk/news/latest-news/british-army-still-more-horses-28014993 [Accessed 1 Jan. 2024].

GOV.UK. (n.d.). UK military dog to receive PDSA Dickin Medal after tackling Al Qaeda insurgents. [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-military-dog-to-receive-pdsa-dickin-medal-after-tackling-al-qaeda-insurgents.

Holmes, R. and Internet Archive (2005). Tommy : the British soldier on the Western Front, 1914-1918. [online] Internet Archive. London : Harper Perennial. Available at: https://archive.org/details/tommybritishsold0000holm [Accessed 1 Jan. 2024].

Jenk, J. (2019). ‘The Mercy Dogs of World War I’ Dogs in Health Care: Pioneering Animal-Human Paternships. Jefferson..

Scalabrino, G. (2020). Afghanistan: a case study in IED harm. [online] AOAV. Available at: https://aoav.org.uk/2020/afghanistan-a-case-study-in-ied-harm/.

Singleton, J. (1993). Britain’s Military Use of Horses 1914-1918. Past & Present, [online] (139), pp.178–203. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/651094?seq=1 [Accessed 30 Dec. 2023].

Somerset, C. and Gough, J. (1857). Letters from head-quarters, or, the realities of the war in the Crimea. London: J.Murray.

team, T.N.A. web (n.d.). Horse census – The National Archives. [online] Home front stories. Available at: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/first-world-war/home-front-stories/horse-census/#:~:text=During%20the%20First%20World%20War [Accessed 26 Dec. 2023].

www.fusiliersconnect.com. (n.d.). Regimental History. [online] Available at: https://www.fusiliersconnect.com/about/fusiliers-family/regimental-history#:~:text=In%201829%20King%20George%20IV [Accessed 4 Jan. 2024].

www.nam.ac.uk. (n.d.). Battle of Balaklava | National Army Museum. [online] Available at: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/battle-balaklava.

www.nam.ac.uk. (n.d.). Royal Army Service Corps | National Army Museum. [online] Available at: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/royal-army-service-corps [Accessed 30 Dec. 2023].

www.nam.ac.uk. (n.d.). The British Army entrusted its secrets to birdbrains | National Army Museum. [online] Available at: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/british-army-entrusted-its-secrets-birdbrains.

www.paradata.org.uk. (n.d.). Kenneth Rowe | ParaData. [online] Available at: https://www.paradata.org.uk/people/kenneth-rowe [Accessed 3 Jan. 2024].

[1] team, T.N.A. web (n.d.). Horse census – The National Archives. [online] Home front stories.

[2] Calthorpe, Somerset John Gough (1857). Letters from Headquarters: Or, The Realities of the War in the Crimea, by an Officer on the Staff. London: John Murray. p. 132.

[3] Curator (2022). A Brief History of The Regimental Mascot. [online] Royal Welsh Museum.

[4] Gardiner, J. and Internet Archive (2006). The animals’ war : animals in wartime from the First World War to the present day. [online] Internet Archive. London :

[5] Singleton, J. (1993). Britain’s Military Use of Horses 1914-1918. Past & Present, [online] (139), pp.178–203. Page 139

[6] Singleton, J. (1993). Britain’s Military Use of Horses 1914-1918. Past & Present, [online] (139), pp.178–203. Page 178

[7] www.nam.ac.uk. (n.d.). Royal Army Service Corps | National Army Museum. [online] Available at:

[8] Baker, C. (n.d.). The Royal Artillery in the First World War. [online] The Long, Long Trail.

[9] Cooper, J. and Internet Archive (2000). Animals in war. [online] Internet Archive. London : Corgi. Page 47

[10] Singleton, J. (1993). Britain’s Military Use of Horses 1914-1918. Past & Present, [online] (139), pp.178–203. Page 203

[11] Holmes, R. and Internet Archive (2005). Tommy : the British soldier on the Western Front, 1914-1918. [online] 417

[12] Gleadow, E. (2022). British Army still has more horses than tanks, even though beasts useless in war. [online] Daily Star.

[13] www.nam.ac.uk. (n.d.). The British Army entrusted its secrets to birdbrains | National Army Museum.

[14] Gladstone, H.S. and Smithsonian Libraries (1919). Birds and the war. [online] Internet Archive. [London, England] : Skeffington & Son. Page 3

[15] Baker, C. (n.d.). Carrier Pigeon Service. [online] The Long, Long Trail.

[16] Anne Kelley (2021). State Library Victoria Pigeon messengers of World War I. [online]].

[17] Baker, C. (n.d.). Carrier Pigeon Service. [online] The Long, Long Trai

[18] Cooper, J. and Internet Archive (2000). Animals in war. [online] Internet Archive. London : Corgi. Page 73

[19] Baker, C. (n.d.). War Dogs in 1914-1918. [online] The Long, Long Trail.

[20] Dogs of war: How man’s best friend joined him at the front. (2014). BBC News.

[21] Cooper, J. and Internet Archive (2000). Animals in war. [online] Internet Archive. London : Corgi. Page 78

[22] Schilp, Jill Lenk (24 September 2019). “The Mercy Dogs of World War I”. Dogs in Health Care: Pioneering Animal-Human Partnerships. Jefferson, page 20

[23] “Military working dogs parade as a newly formed regiment”. British Army. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

[24] 1st Military Working Dog Regiment”. British Army.

[25] archives.the-monitor.org. (n.d.). Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor. [online]

[26] Scalabrino, G. (2020). Afghanistan: a case study in IED harm. [online] AOAV.

[27] www.paradata.org.uk. (n.d.). Kenneth Rowe | ParaData. [online]

[28] Forces Network. (2014). Hero Army Dog Given Posthumous Award. [online]

[29] GOV.UK. (n.d.). UK military dog to receive PDSA Dickin Medal after tackling Al Qaeda insurgents. [online]

[30] Gardiner, J. and Internet Archive (2006). The animals’ war : animals in wartime from the First World War to the present day. [online] Internet Archive. London : Portrait. Page 99

[31] www.fusiliersconnect.com. (n.d.). Regimental History.