Wordcount: 3267

“A well-turned line of script can sometimes carry more weight than all the scholarly footnotes in the world.”

Richard Holmes, 1999

Introduction

This page will present the research that identifies how British Military Disasters have been portrayed within popular culture throughout history. It will identify the different forms, their popularity and how they have affected the public support for the Army as a whole, and support for their operations. Furthermore, the issues regarding the public acknowledgement of British involvement in disasters and how the Army portrays itself in the modern age.

This page also identifies ways in which public opinion changes depending on the type and amount of coverage of events in the British Militaries past and will highlight how the different types of popular culture have affected public opinion in different ways. The research below shows the clear trend that in the past, newspaper reports and eventually media on the radio were what directly affected public opinion as it was often easier to hide the extent of disasters from the public, making public opinions easier to manage. However, within the modern age, the trend of media affecting public opinion is more significant and should be targeted, prompting the British Army to learn from mistakes and ensure action is taken accordingly regarding their current military operations.

Problems With How the British Army Is Portrayed

The recent defeat and subsequent withdrawal from Afghanistan have caused the public to question the competence and effectiveness of the British Army (Mackay, 2021). The media has often portrayed the British Military, in this case, to have wasted their time in Afghanistan, often using examples of public opinion within articles to set the tone, with language like “what did we achieve? What was the sacrifice for? Because it is too high a price to pay” (Mackay, 2021). This same example provides evidence for how the British Army presents itself. It includes direct quotes from leading British Military members expressing words of regret and remorse over lost soldiers and the good that they were able to achieve while deployed. Furthermore, the British Military seems to refuse to talk about defeat or loss in a way that implies the failure of their campaign, which provides a pattern and valuable basis for analysing past examples of British Army disasters throughout history and how they have been portrayed in popular culture to the public.

“Any evaluation of the campaign must prioritise genuine investigation over reputation management”

Simon Akam, 2021

This pattern often repeats itself throughout history, with different military disasters being portrayed differently to the public. Often in the years before widespread and easy to access news became available, the public would know little about what was happening on the battlefields the British were engaged on until letters from men serving were received, which often left out details of what was occurring during the campaigns. The overall theme across public opinion and expert opinion regarding recent British military defeats are that of acknowledgement the British Army is more likely going to protect its reputation rather than learn from its mistakes as Simon Akam (2021) states, “Any evaluation of the campaign must prioritise genuine investigation over reputation management”. This attitude towards the British Army has been common throughout recent years, with the British Army defending itself and its actions.

Furthermore, a pattern often emerges of the British military defending themselves and their actions in times of defeat; depending on the period, censorship of critical sources of information such as the news may have been in place, but the trend remains. The Allied withdrawal from Dunkirk and the news reports surrounding this are good examples of censorship and blame-shifting. It is rare to see popular culture which directly acknowledges the shortcomings of the British Army as examples from the time show the blame being shifted onto the Belgians and the French rather than admitting British mistakes as newspapers often reference ‘the evacuation from Flanders’ rather than Dunkirk (The British Newspaper Archive, 2017). Often during wartime, censorship of information leaving the battlefields was common and often what influenced the formation of overall public opinion and beliefs regarding events, with examples of newspapers from 1940 stating the British Army was ‘intact’ and ‘powerfully entrenched’ at Dunkirk, which history shows, was somewhat of an exaggeration.

Despite their failures, the British Army has been portrayed in books, film, news, and music with apparent high regard for the Army. This attitude has persisted over time, and now most people in Britain, especially older people, have a high opinion of the Armed Forces. When asked, eight out of ten say they have a high or extremely high opinion of the Armed Forces (BSA, 2012).

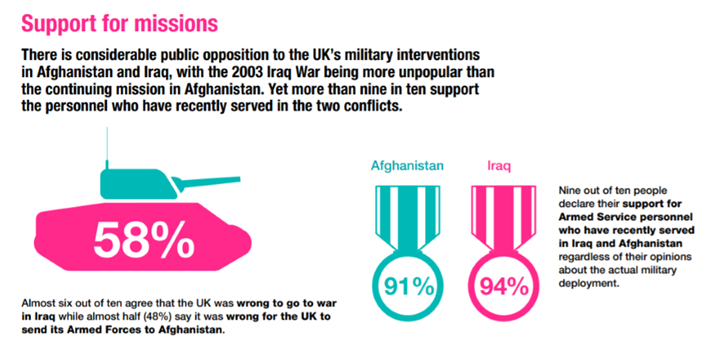

British Army disasters which make their way into popular culture have had an impact on the way the British Army is viewed, often the support for the Army as an establishment is low, with the example of how public opposition regarding the UK’s military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, with these missions being deeply unpopular with the public, however, despite this more than nine in ten support the personnel who have recently served in the two conflicts (BSA, 2012). This is undoubtedly thanks to the portrayal of the British Army in the news during and following the conflict, as often stories of individual heroics would become well known within public circles. At the same time, the information provided regarding the military disasters often blamed the British Army command and the establishment itself. The example of the battle of Rorkes Drift, which was portrayed in the 1964 film Zulu, shows the courageous actions of British soldiers in the face of overwhelming odds. This film also portrays the British Army command as overconfident in dealing with the conflict, resulting in The British Army’s worst defeat against an indigenous foe equipped with vastly inferior military technology at the Battle of Isandlwana (Clammer, 1973).

Other than the news, the use of literature and art to convey information regarding wars and subsequent military disasters had evident popularity in the decades before television appeared, often with works that showed in great detail how scenes of battle looked. While great paintings were created, they would often be by an artist employed by the British Military who would later receive the painting, meaning the general public would be very unlikely to see them.

The example of ‘The Royal Horse Guards Retreat from Mons, 1914’ by Elizabeth Southerden Thompson Butler in 1927 shows this, as military higher-ups primarily saw it, and while one was displayed in The Royal Hospital Chelsea, the painting did not reach the masses at the time. However, what more directly impacted popular culture was the introduction of illustrated news articles, primarily from Illustrated News London founded in 1842, which showed graphic images of battles and detail on events during wartime.

While these images were initially based on reports and photographs, the demand for direct renditions of battle scenes from the battlefield itself during the Crimean War meant a shift towards much more realistic and graphic scenes of fighting. Therefore, these illustrations impacted the public’s view of war, and unlike previously, the British public had access to information about British military disasters, which directly influenced public opinion of the British Military.

The British Army in modern popular culture is now reaching the masses via television and film, which has had the most significant impact on public opinion of the Army by providing a platform for greater, more accessible news coverage of events during war, while also providing the ability for independent filmmakers to create a form of media which reaches and appeals to more in the contemporary setting than the news would. Media is one of the most crucial elements of pop culture that affects the British Army’s image regarding its disasters because it is diverse, satirical and serious, which increases the breadth of the audience it reaches.

An excellent example of a satirical representation of the disaster that was the Somme campaign is ‘Blackadder Goes Fourth’, which aired in 1989; both journalists and historians have described it as a television series that presents a pervasive view of the war in the public’s perception of World War I (Hanna, 2009). Richard Holmes supports this in his book ‘The Western Front (1999) where he says, “A well-turned line of script can sometimes carry more weight than all the scholarly footnotes in the world.” This comment supports the point that media has a more significant impact on the public’s view of the British Army, especially when it is a military disaster being portrayed.

The Media and the invention of the television saw a massive uptake amongst the general public and meant that news and information reached almost every person. As previously mentioned, it is much more likely that a member of the public will respond to something visible or available for them to see for themselves. This links to the war paintings, the illustrated newspapers and then eventually to the media with actual pictures and videos being shown to the masses. The contrast between the First and Second World Wars for example, where the access to media and the impact on public opinion was clear.

In the First World War, which was not just before the internet but before television and even widespread public radio meant that war news for the vast majority of the public came via the written word, either through newspapers or letters, which the Government did its best to censor (Demm, 2017). At the time, it was difficult for the public to find out about British military disasters which took place during the war; with the Somme as an example, much of the public was unaware that so many had perished, with almost 20,000 British troops killed in action on the first day of the campaign as the British Government censored much of the information reaching the home front, which made it the case that many were surprised once they found out in popular culture after the war when censorship was removed (Demm, 2017).

Often British Military disasters are portrayed in popular culture either from the point of view of the British, which will more often than not either gloss over the disaster and focus on a more positive note, with the example of the 1964 feature film ‘Zulu’ which does acknowledge the total defeat at the Battle of Isandlwana, 1879 yet seems to gloss over it and uses it to set up the ensuing battle at Rorkes-Drift (David, 2011). The pattern of promoting the victory at Rorkes-Drift is clear as even from the time dramatized paintings depicting brave steadfast British soldiers fighting Zulu warriors were created, notably the painting by Elizabeth Butler known as ‘The Defence of Rorkes-Drift’ in 1880. The British Military employed Elizabeth Butler as a military painter, which most likely due to military pressure, caused her work to favour the British heroism rather than the fact British soldiers only survived due to being spared by the Zulu warriors. Therefore, both of these examples follow the previously mentioned patterns that the British Military will want to portray itself to be competent and ignore their past disasters, which spills into the media and, therefore, into the public’s view of the British Military.

As some of the previously mentioned examples show, The First and Second World War are critical examples of how British Military Defeats and blunders are portrayed in popular culture as it was at this time that the news, poems, and literature was becoming more accessible and readily available to the masses (Cannadine, 2004). During and after this period, more and more examples of British Military disasters appeared in popular culture, as especially after The Second World War, much more of the public was receiving much better levels of education. Therefore, they were being exposed to more literature, meaning a greater number of people were learning about previous British Military disasters, with an example of the ‘Charge of The Light Brigade’ poem depicting a British Military blunder which became even more popular within the greater British public during the interwar years (Hamilton & Shepherd, 2016).

Furthermore, due to the increased education of the public before and during both the First and Second World Wars, many of the soldiers would publish their accounts of battles and their experiences following the wars, which had a significant impact on popular culture regarding how the British Army is viewed and how people now understand that as an institution the British Army is likely to hide or play down defeats and disasters which occur in the modern day (Akam, 2021).

British Army Image in Popular Culture Overall

| How much confidence do you have in Britain’s armed forces to be able to defend Britain? | 2019-11-11 | 2020-05-03 | 2020-10-18 | 2021-04-05 | 2021-09-19 |

| A lot of confidence | 17% | 20% | 16% | 15% | 13% |

| A fair amount of confidence | 44% | 44% | 43% | 40% | 43% |

| Not very much confidence | 21% | 18% | 21% | 26% | 22% |

| No confidence at all | 4% | 4% | 5% | 6% | 7% |

| Don’t know | 13% | 13% | 15% | 14% | 16% |

| Unweighted base | 1679 | 1655 | 1665 | 1618 | 1790 |

| Base | 1679 | 1655 | 1665 | 1618 | 1790 |

In general, the overall confidence in the British Armed Forces remains relatively strong, and support does remain behind the Army, despite their previous failures, as the data above shows (YouGov, 2021). However, there is a pattern of a decrease in public confidence and support when new British Military disasters reach popular culture or when a new piece of popular culture covers a disaster from the past, like A Bridge Too Far or Dunkirk (YouGov, 2021). While the provided evidence shows that public confidence and support for the Army falls when this happens, the main criticism is never of the soldiers themselves, but rather the Army as an institution which will often attempt to ignore or hide its failures from the past and attempt to dampen the effects of mistakes they make in the modern-day (Akam, 2021).

“A film that will doubtless become the definitive cinematic depiction of this remarkable chapter of history”

Mark Kermode, 2017 on ‘Dunkirk’

Furthermore, the trend in contemporary society is that the visual representation of the horrors of warfare creates a more significant response from the public. If this is seen in a piece of media regarding a British Military failure, it often causes greater criticism of the British Military (Cannadine, 2004). However, with the release of Dunkirk in 2017, another example of what can happen within popular culture regarding British Military disasters is that public support can rally behind a particular aspect of the disaster, with the Dunkirk film seemingly reinvigorating the old ‘Dunkirk spirit’ which creates a sense of unity and public support for the nation and the Army, seen with the many glowing reviews of the film itself with Mark Kermode (2017) stating “a film that will doubtless become the definitive cinematic depiction of this remarkable chapter of history”, which shows a clear level of support and the rest of his article provides a view which supports and praises for the film, its subject and those involved in the real-life event (Kermode, 2017).

During 1916 an example of how media impacts more people is seen as, over 20 million Britons watched the first feature-length war documentary ever called ‘The Battle Of The Somme’. It used both staged footage and real battle scenes captured between June 25 and July 9 and was expected to be a great film depicting a British victory. However, the film caused controversy by including footage of the true horrors of war and the military disaster of The Somme, with the inclusion of scenes of corpses being tossed into communal graves and the general carnage and conditions the Allied soldiers were living in. While this was the case, the film still paved the way for the future of British war films as it proved the popularity of the subject with over half of Britain’s population viewing the film in cinemas around the country.

The average theme within the public opinion of the British Army is one of trust in those who are serving and those who have served while being more sceptical of the Army as an institution and its operations (Dandeker, 2013). The fact that many members of the public are directly linked to the Military with members of family and friends being employed by them, coupled with the pattern of popular culture to always portray British Military personnel as heroes fighting for good causes, results in numbers of over 90% of the public stating they support Armed Forces personnel regardless of their opinions about the missions (Dandeker, 2013).

The example of a film that depicts a British Military disaster and follows the pattern of showing the Military command as either incompetent or uncaring while showing the soldiers on the ground as heroes placed in a challenging situation is ‘A Bridge Too Far’ 1977. This film’s portrayal of the events of the failed ‘Operation Market Garden’ is accurate and exciting, with reviews stating that the film provides scenes which are ’a triumph, visceral and memorable’ with direct reference to the impact the film has on those who watch it (Tunzelmann, 2009). This supports the apparent fact that the British Army’s image is linked to how they are portrayed in popular culture, especially within forms of the media.

Therefore, this makes it clear that the image of the British Army within popular culture, in general, is one of respect for the soldiers on the ground with an inherent lack of respect for those commanding them (Dandeker, 2013). Furthermore, clearly the most influential pieces of popular culture were the news and media from the 1850s onwards, this coupled with the improvements in general education and the means to tell a uniform story about events in the world, allowed the public to form their own opinions regarding the British Army and their operations overseas.

The Future Of The British Army’s Image In Popular Culture

As previously explained, the news and the media have a significant impact on the public image of the Army and depending on events of the time, popular culture shows the mindset of the public at the time and therefore give greater insight into the views of the British Army (Leigh, 2022). As such, with new films being released in 2022, the general tone of public views can be found, with the new film ‘Munich: The Edge of War’ and ‘Operation Mincemeat’ where both present a patriotic view as most British war films do, yet these now come with caveats. Compared to the previously mentioned war films like Zulu and Dunkirk, the atmosphere is clearly less than triumphal according to Danny Leigh (2022), who explains that ‘Operation Mincemeat is a tale told with the larky air of a heist movie, cynicism colours it too’. This shows a clear shift away from the usual patriotic pieces within popular culture as the general context around the films has shifted.

The last major war film, Dunkirk, was released at the height of the Brexit campaigns, which helped reinforce the ‘Dunkirk Spirit’ and improved the public view of the Army, despite the film being about a significant military disaster. Now Britain has seen the consequences of Brexit during a global pandemic and the news reporting the complete failure of the British Army in Afghanistan, which has soured the public’s view of the British Army (Akam, 2021), and has made its way from the news into the media side of popular culture with the much darker and less optimistic sense of patriotism presented by the two mentioned 2022 war films (Leigh, 2022).

Conclusion

To conclude, popular culture has had a significant impact on the public image of the British Army, especially concerning the formation of opinions regarding their disasters. The news and media are the most important form of popular culture in impacting the public view over time due to their accessibility and popularity. To summarise –

- The news and media have the most significant impact on the public image of the British Army.

- The surge and fall of patriotism caused by the context of the time that popular culture pieces were released in, heavily impacts the British Army’s image to the public.

- Modern connectivity and access to information worldwide makes censorship and the management of public opinion difficult, meaning a greater understanding of the public’s view of the Army is provided.

- A common trend of support for the soldiers serving, and distrust of those in command is evident within the public.

Bibliography

Akam, S., 2021. Britain’s military will want to ignore its failure in Afghanistan. It must face reality. The Guardian, 22 August. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/aug/22/britain-military-failure-afghanistan-campaign [Accessed 29 December 2021]

Akam, S., 2021. The Changing of the Guard: The British Army Since 9/11. Brunswick, Victoria: Scribe Publications.

BSA, 2012. The UK’s Armed Forces: public support for the troops but not their missions? British Social Attitudes. Available at: https://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk/latest-report/british-social-attitudes-29/armed-forces/introduction.aspx [Accessed 29 December 2021]

Cannadine, D., 2004. History and the media. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Clammer, D., 1973. The Zulu War. Newton Abbot: David and Charles.

Dandeker, C., 2013. Are the UK armed forces understood and supported by the British public?, Available at: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/kcmhr/research/kcmhr/publicperceptionshandout.pdf [Accessed 4 January 2022]

David, S., 2011. Zulu: The True Story. British History in Depth. BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/zulu_01.shtml [Accessed 2 January 2022]

Demm, E., 2017. Censorship. 1914-1918 Online, 29 March. Available at: https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/censorship [Accessed 1 January 2022]

Haggard, H. R. & Kerr, C. H. M., 1893. The Tale of Isandlwana and Rorkes Drift. New York: Longmans, Green. pp. 132–152.

Hamilton, C. & Shepherd, L. J., 2016. Understanding popular culture and world politics in the digital age. New York: Routledge.

Hanna, E., 2009. The Great War on the Small Screen: Representing the First World War in Contemporary Britain. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132.

Holmes, R., 1999. The Western Front. London: BBC Worldwide Ltd. pp. 17.

Kermode, M., 2017. Dunkirk review – utterly immersive account of Allied retreat, The Guardian, 23 July. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/jul/23/dunkirk-review-terrifyingly-immersive-christopher-nolan [Accessed 2 January 2022]

Leigh, D., 2022. Battle fatigue: will British cinema’s second world war obsession ever end?, The Guardian, 7 January. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/jan/07/battle-fatigue-will-british-cinemas-second-world-war-obsession-ever-end [Accessed 8 January 2022]

Mackay, H., 2021. UK military not defeated in Afghanistan, says head of British armed forces. BBC News, 9 July. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-57774012 [Accessed 28 December 2021]

National Army Museum, 2019. Drawn on the spot: War artists and the illustrated press. Available at: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/illustrated-press [Accessed 1 January 2022]

Paris, M., 2002. Warrior nation images of war in British popular culture, 1850-2000. London: Reaktion.

RTE, 2016. Gallipoli In Popular Culture, Available at: https://gallipoli.rte.ie/guides/gallipoli-in-popular-culture/ [Accessed 2 January 2022]

The British Newspaper Archive, 2017. Dunkirk Stories. The British Newspaper Archive, 24 July. Available at: https://blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/2017/07/24/dunkirk-stories/ [Accessed 29 December 2021]

Tunzelmann, A, V., 2009. A Bridge Too Far, for allied forces and for viewers, The Guardian, 16 July. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/jul/15/a-bridge-too-far-reel-history [Accessed January 2022]

YouGov, 2021. Confidence in the British armed forces in defence, Available at: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/economy/trackers/confidence-in-the-british-armed-forces-in-defence [Accessed 2 January 2022]