Regardless of the type of media, it always reflects the attitudes of the moment. Recruitment materials, just like any media exist as products of their time. In the story of the military recruitment advert, societal shift, and the way a society views the military are the driving forces behind its evolution, and the updating abilities of a society expand the pathways down which this evolution becomes apparent.

Why start with the first world war?

Firstly, the first world war is a good place to start as it is one of the first major, and if not the first certainly the largest and most urgent recruitment drive undertaken by the military and government so far. Up until this point the empire has been generally sufficient for manpower, and such a drastic and immediate need for men has not been required.

A second reason comes from the foundations that good advertisement and ergo good recruitment material is built on. Psychological and persuasive technique and technological reach that can penetrate the target audience. Over the 20th Century a great deal of research and breakthroughs occurred in both of these fields. Using the first world war as the comparison point, when these were in their infancy, really allows the transformation over time to be shown clearly, and details to be pointed out.

So, with that out of the way:

What are the major themes and strategy encompassing First World War recruitment materials?

Many themes run through material from this era, the primary, and probably most recognisable one is one of naivety in relation to it’s subject matter. Campaigns paint an image of military service that is far detached from the realities of what is to come, where the main takeaway from analysing many posters and leaflets is that military life is joining vast swathes of khaki clad men and telling more people to sign up. This idea of naivety and its involvement in recruitment campaigns will come up again later in a slightly different form. For now though it is important to note that the naivety may not be a tactic, but, remembering the introduction, a trait of the society at time. It is a rather well known fact that the general public and indeed many people were generally less clued up about the realities of conflict. Especially this new form of conflict that would come on such a large scale between two wealthy and driven modern powers. A culture of naivety you could go as far to call it ran through British society.

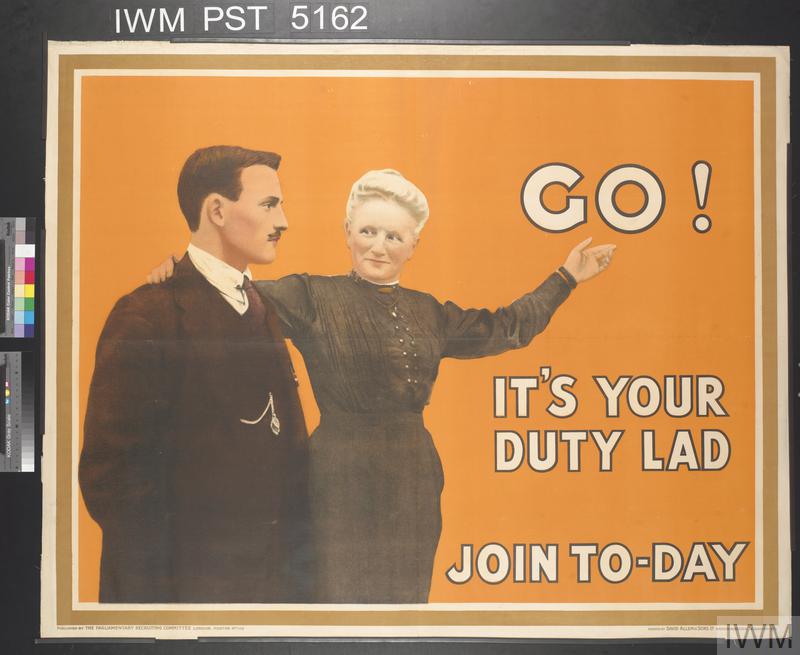

Perhaps the second major aspect of this era of adverts is the overarching theme that wanting ‘you’ to join up (‘you’ being the young man being targeted) isn’t just something desired by the army, or the government, but the whole of British society. In this example bellow we have an older woman figure, perhaps a mother, grandmother, doing the persuading to the young man in question. I say mother or grandmother but really this figure more likely is a stand in for any woman of social authority in Edwardian era life. Somebody that socially or morally you wouldn’t want to disappoint.

In terms of background psychological techniques and targeting, material made by the PRC is rather more bare than will be found in its modern counterparts. Outside of common persuasive literary devices there isn’t that much more most likely due to the fact that much of the psychological research in this field simply hadn’t been completed yet. One area that is of interest and links into this, deliberate or not is the use of ‘you’ as previously mentioned. With the implication that more or less the whole of society is backing them it places the pressure for joining directly on the individual. Moreover though, this theme becomes more effective as it allows the target audience to consider the consequences and effects of not joining up. Going back to the heroism themes, not joining up implies the opposite, that ‘you’ are not heroic, in the earlier example, that the target is actively not becoming a man. The material makes men question their self-worth. Societal disappointment really comes to a head in the example here

Here the scenario painted is perfectly feasible, and on top of causing reflection in the individual it attacks a crucial aspect to Edwardian social life, the role of respect and hierarchy in the household. What will be the consequences when asked by your children?

Creation and success

Before going on to compare this material with a more contemporary variety, it would be amiss not to have a brief foray into the ideas behind its creation and analyse the successes of the technique. The materials produced at this time were overseen / governed by the PRC, or Parliamentary Recruitment Committee. This was a body formed after recognising the experience in political advertising, community liaison and rallying was held within the political parties themselves. Important to note for later in this article is the sentiment about which the materials were created. That it should be communicated by the PRC that ‘the grave issues of the War should be fully comprehended by the people and thereby give a powerful impetus to recruiting’[1].

To touch on scale and reach of the campaign, 20 million leaflets and 2 million posters had been produced by march of 1915[2]. Town meetings about the war effort and recruitment fulfilled the community liaison aspects of the campaign, moreover, screenings in cinemas could be seen as utilising popular media.

Success is an interesting thing to judge as there are the differences between numbers, and the eventual effects of these numbers. Over a million men did manage to be recruited in the one and a half years following the start of the PRC’s efforts. In terms of more precise rate of joining, on the 10th of September it is said by Asquith that 439000 men had been recruited[3]. Additionally, In the prior 10 days to his report that each day the number recruited was ‘the same number of recruits in past years that had been recruited every year.’[4] These are impressive figures, and the day on day rate equalling out to years is a strong uptake that correlates with the PRC’s content. In 1916 though conscription still has to be introduced. The overall campaign was certainly successful in its own right, however fell short when it came to providing enough for the entire war.

Contemporary recruitment materials

As mentioned in the beginning it is often societal shift that can give clues as to why these changes took place. Therefore, before looking at the materials this section will lead on from the context of the First World War and look at the world in which these new adverts inhabit, and the reason they, and their methods are required.

Economic benefit and the crisis of recruitment

When discussing modern recruitment campaigns, the words ‘crisis of recruitment’ are cast around often. Modern material is therefore created in a way to get around this so called crisis. But what societal factors have formed the crisis itself?

Economics play a major role in the recruitment of a society into the military. This is heightened in a modern liberal democracy, and the transition away from mandatory conscription towards an AVF, or All volunteer force. By removing conscription, the military organisation in question is forced to become a participant in the private labour market, one where military service is immediately at odds with a major concept in the modern neo liberal world: the ‘enterprising self’[5]. The enterprising self model dictates that an individual is an active participant in an economy, one who searches for a ‘sense of meaning, responsibility and a sense of personal achievement in live [and] work’[6]. In seeking out employment, the enterprising self is expected to work within this framework. The military organisation, the British army in this case, is at the end of the day a government body and subject to the limited resources that go along with that. It is hard for an AVF to compete with the salaries offered by private companies[7]. This is one of the major reasons why militaries go through periods of lower recruitment when there is economic fortune in a country, and the UK unemployment rate being one of the lowest since the early 1970s will have factored into their recruitment struggles.

Another factor that goes into the crisis is the nature of these individuals. With the rise of the internet and modern culture, societies have moved away from collectivist identities and towards more individual expression and identification. Communities nowadays are more split, young people especially are less likely to align and belong to Unions or Political parties[8]. Participation in religion is also dropping alongside this. As individualism rises, so does scepticism towards organisations and groups that are collectivist in nature, of which a military organisation, traditionally, is a prime example.

A reason conscription ended and one of the aspects of this crisis of recruitment go hand in hand, that being the transition over time of perceived threat to a nation. As global tension wound down or got relocated away from home for Europe especially, many countries underwent a transition from a required conscription to having a volunteer force and a smaller professional army. This transition of level of threat has also been perceived by the public and created a perspective that military missions have changed from ‘wars of necessity’[9] to ‘wars of choice’[10]. This may not sit as well with possible recruits. The UK’s involvement and public response to the in Iraq for instance could be a good example of this.

A final aspect of the recruitment crisis is retention of recruits that do sign up. This phenomenon will be looked at in greater detail in the following section about modern materials. Recruiting members younger, at 16-18 does get more people signing up, however this age range is also most likely to leave training early. On top of this is issues in retention of people undergoing the application process. There are widespread criticisms of Capita, the company outsourced to manage the application process, where there is a frustrating cycle of bureaucracy and 300 day wait times to be accepted into the Army. In 2017, 7500 applicants finished the application process out of the over 100,000 that started[11].

The cumulative effect of these factors on the British Army has been them, in 2019, running 30% short on their recruitment targets[12].

Trends and themes in modern materials

Consequently, to deal with this, the British Army, alongside the other services has had to try and appear attractive in the private labour market, becoming a ‘consumer brands’[13]. Creating campaigns which show what the organisation can provide to the customer, here the potential recruit. Campaigns which focus on ‘selling the dreams of the consumers’[14]

A primary method they focus on in this effort is displaying the Army as the best place, and perhaps the only place if you view it from a certain angle, to achieve personal fulfilment. They have created a simplified brand image focusing on themes of adventure[15], comradeship, and a rewarding career. Clips of young adults playing football on a beach, groups bearing insignias getting into horse play are mainstays of this era of campaigns. By simplifying it however they have seemingly missed out a large proportion of military life, for instance the realities of what conflict might entail, and obligations that go alongside the supposed kayaking and banter. Well, why is this and what can it tell us about the motive behind the campaigns? If the answer you go to is along the lines of well of course they wouldn’t show a more realistic aspect, don’t be silly, that wouldn’t sell at all, especially to young people then you’re pretty bang on to the reason. If we go back to the idea of the culture of naivety in the first world war, that doesn’t really exist anymore in the modern world. Building on the enterprising individual from earlier, people are aware nowadays of, true or not, the most visible negatives of a military career in the situation they are in. Today then, it could be said the Army is trying to cultivate this culture of naivety in its campaigns in order to net more recruits. If you move on from this standpoint it is not the greatest mental jump to find that the area where naivety is most commonly found is young people. This idea gains greater prevalence when re analysing the messages in the material. Finding a place to fit in (but also being able to be yourself[16]), finding something you’re good at, proving to people – and family – that you can do better than they think, a lot of the emotions that are targeted by the adverts can be linked together with one common factor. They are all common adolescent fears. These adolescent themes can be seen in the example bellow, with note to the shoe character, a possible reference to modern lifestyle vloggers who’s main audience is a adolescent demographic.

Adolescence plays a major role in contemporary British Army recruitment. With adolescence young people are far more likely to make decisions based off emotions rather than logical processes, or for perceived emotional benefit. Inhibitory control is developed far later than the ability to act on urges that comes before it[17]. Adverts that target this group and these factors are going to be more effective and have a higher draw. It is no surprise that they resemble in some cases pop music videos – types of media that specifically are designed for young and adolescent audiences. Young people are less likely to be aware of all the options and career paths available to them upon leaving education, and therefore less attached to the ‘enterprising self’ model. Due to the weight emotion has on their choices they are also easier to sucker in with promises of adventure without as strong consideration to other factors they may have to deal with in their choice.

The importance of adolescence and young people is so crucial now to the Army’s campaigns that they have started to include into adverts what could be called gatekeeper material. As much as young people may be easy to sucker in with the glossy campaign being pushed, the Army is aware of parents, guardians and other members of the targets network who are able to provide counter opinions. Parents might think more about the realities of military life and action, they may have questions or even know about legal obligations, risks to their child, the terms of the contract. These figures are known as gatekeepers. Gatekeeper material in campaigns aims to do 2 things. Firstly it can try and alleviate concerns held by the gatekeepers, and portray an image that the Army is a better place to send a child[18]. Secondly, it can attempt to drive a rift between the potential recruit and their guardians, having the target question whether their guardians have their best interests at heart. ‘If the Army can make me into a better me, why don’t my parents want that aswell?’. Their guardians become obstructions to joining. Nowhere can this be seen more clearly than in the, now unfortunately pulled ‘Don’t join the Army, don’t become a better you’ campaign from 2016, which actively shows an interaction like this between a farther and son figure. If I could find a creditable version of this campaign to insert here I definitely would, however the best I can find is a dodgy video of someone filming a television >:(.

There have been instances in recent years of a less sanitised advertisement approach, for instance the ‘Torchlight’ campaign from 1998. This is quite the tonal shift from more modern material and possibly couldn’t work today because of the darker tone colliding with the demographics they target.

Creation and success

It is harder to directly compare successes between first world war and current material. The effects of the current series of campaigns have not fully played out yet. There is a general downward trend in in recruitment, and a persistent gap between the current numbers and the goal set by the government. Whereas in WW1 there had to be a large scale physical media campaign, the arrival of the internet has of course changed that. Aside from less trees being cut down though a more important arrival is one of being able to track individual consumers. Being able to target adverts to the most vulnerable has far increased efficiency in the process. It can be possible to narratively track an applicant’s journey via the use of targeted ads.

Summary of similarities and differences

So, now that both first world war and contemporary material have been looked into, what are the overall changes in theme and technique? Well, I’d say the primary feature that stands out is that a lot of the themes or topics employed and explored by modern adverts are actually very similar. Similar in image perhaps, but what has changed is the tone or direction these motifs are played in. If we take the motif of society wanting men to join the Army as it is the just and correct thing to do and compare it to today, then the theme of society is still present. What has changed though is the message, from society backing you up to join, to society not seeing what you are capable of / believing in you and how you can show them better by joining the Army.

An aspect that is definitely still present but perhaps less changed is the way both forms of advert can induce the viewer to question their self-worth and position. The emphasis on the direction this reflection goes in though is slightly different. First world war material makes the viewer question what they are doing by not joining the army. The material looks at the benefits and what it means to sign up and fight for the country. The most recent Army campaign presents more simple, homogenised benefits such as general lasting confidence, and throws the viewer negative aspects that they can attach to themselves by staying a civilian. They are very similar techniques, however, to simplify it, old materials focus on positives to the military, current ones build on this by directly giving negatives to being a civilian.

References

Dawson G. Soldier heroes: British adventure, empire, and the imagining of masculinities (London, Routledge, 1994)

Douglas R, ‘Voluntary Enlistment in the First World War and the World of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee’, The Journal of Modern History, 42:4 (1972, The University of Chicago Press) p.564-585

Jester N. ‘Army recruitment video advertisements in the US and UK since 2002: Challenging ideals of hegemonic military masculinity?’, Media, War & Conflict, 4:1 (2019) pp.57-74

Hines L et.al. ‘Are the Armed Forces Understood and Supported by the Public? A View from the United Kingdom’, Armed Forces % Society, 41:4 (2014) pp.688-713

Kempshall C. ‘Pixel Lions – the image of the soldier in First World War computer games’, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 35:4 (2015) pp.656-672

Louise R & Sangster E. ‘Selling the Military: a critical analysis of contemporary recruitment marketing in the UK’ (ForcesWatch & Medact, 2019)

Strand S & Berndtsson J. ‘Recruiting the “enterprising soldier”: military recruitment discourses in Sweden and the United Kingdom, Critical Military Studies, 1:3 (2015) pp.233-248

[1] Douglas R, ‘Voluntary Enlistment in the First World War and the World of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee’, The Journal of Modern History, 42:4 (1972, The University of Chicago Press) p.566

[2] Douglas R (1972) p.568

[3] Douglas R (1972) p.569

[4] Douglas R (1972) p.569

[5] Strand S & Berndtsson J. ‘Recruiting the “enterprising soldier”: military recruitment discourses in Sweden and the United Kingdom, Critical Military Studies, 1:3 (2015) p.235

[6] Strand & Berndtsson (2015) p.236

[7] Strand & Berndtsson (2015) p.239

[8] Louise R & Sangster E. ‘Selling the Military: a critical analysis of contemporary recruitment marketing in the UK’ (ForcesWatch & Medact, 2019) p.10

[9] Louise R & Sangster E (2019) p.7

[10] Strand & Berndtsson (2015) p.234

[11] Louise R & Sangster E (2019) p.10

[12] Francois M. Filling the ranks, Cited in Louise R & Sangster E (2019) p.10

[13] Strand & Berndtsson (2015) p.235

[14] Louise R & Sangster E (2019) p.7

[15] Jester N. ‘Army recruitment video advertisements in the US and UK since 2002: Challenging ideals of hegemonic military masculinity?’, Media, War & Conflict, 4:1 (2019) p.64

[16] Louise R & Sangster E (2019) p.43

[17] Louise R & Sangster E (2019) p.13

[18] Louise R & Sangster E (2019) p.15