The British Cavalry failed to adapt efficiently, to the changing and varied situations it found itself in, during the period of 1853 – 1903.

From 1853 to 1903 the British cavalry saw regular action in colonial wars across Africa. Having sat mostly idle for the previous 40 years, an unprepared army was launched into war in Crimea, and their disastrous fate would prove legendary. The British cavalry was outdated, with a recruitment system based on privilege, and a heavy reliance on traditional swords and knee-to-knee charges. The cavalry were not prepared to fight and live on African terrain, and therefore rapid changes had to occur. During the period there was a series of systematic changes known as the “Cardwell Reforms.” These would help modernise the cavalry and were prompted by the tragedy of the Charge of the Light Brigade.

This webpage will highlight and analyse the changes that occurred to the British cavalry, showing that although reforms did occur, they proved slow to bring about positive effects. Quite often, they were poorly timed and were not fully embraced by those in charge. I have chosen to define the term “cavalry” as the use of horses in offensive operations.

Note that the Indian Cavalry has been excluded from this research. This is because, due to the lack of communication between Britain and India, the Indian Army in practice ran independently. Furthermore, they saw more active service and came across different problems; therefore, they undertook different changes to those analysed here. It should also be noted that many of the changes and reforms spoken about in this webpage did not apply to or occurred at a different time for the British Household Cavalry.

What did the British Cavalry look like in 1853?

By 1853, the British cavalry had not seen major conflict since the Napoleonic wars, 40 years prior, and the army that departed to Crimea in 1853 differed little from that which had fought under Wellington (Chappell, 2002:13). There had occurred little in the innovation of equipment, with outdated weaponry being wielded, such as the sword (Chappell, 2002:13). The cavalry was inexperienced and based on privilege and wealth. In 1853 the only way to become an officer in the British cavalry was to purchase a commission, with the entry rank being a cornet costing £840 (Brighton, 2004:12 and Anglesey, 1975:371). Additionally, there was no required military training, therefore men were promoted on privilege rather than skill. There were exceptions to this, especially from men who had seen experience fighting in India, but more often than not, cavalrymen were untrained and inexperienced in combat (Brighton, 2004:12).

In addition to the purchase system, there was a system of long-term service, which had been in place since 1847 (Anglesey, 1975:269). This meant that cavalrymen joined for twelve years, at the end of which they could either serve another twelve years or be discharged without pensions.

While before the Napoleonic wars, the Heavy and Light Cavalry had performed separate and distinct functions, they were now much the same. The Heavy Cavalry was traditionally heavy men with larger horses, who were reserved to undertake the final charge of battle (Brighton, 2004:10). The Light Cavalry, light men on light horses, completed scouting duties (Brighton, 2004:10). By 1853 they all prioritised the importance of the charge and use of the lance and sabre. This is because, since Waterloo, budget cuts had led to many regiments being disbanded, thus it had become necessary for all cavalry to be prepared to fulfil both functions (Brighton, 2004:10). Furthermore, horses purchased by the cavalry had become heavier, as had their riders (Anglesey, 1975).

What changes occurred during the period 1853 – 1903?

The Rise of the Cape Horse

During this period of 1853-1903, there was a shift towards using more local horses in cavalry operations – this led to the increasing popularity of the cape horse. Horses born through colonialism, the original cape horse or ‘Boerperd’ was a distinct cross between European breeds imported by the Dutch East India Company from Indonesia, combining breeds such as Arabs and Thoroughbreds (Anglesey, 1975:437 and Knight, 2008:103). These horses had then been further shaped by the difficult climate they lived in. The cape horse had bred to produce an even hardier breed – the ‘Basotho Pony.’ These ponies were a result of dealings between Cape settlers and those in southern Sotho (Knight, 2008:104). The high-altitude and tough environments had created a pony of immense stamina, with a skilled ability to navigate rocky terrain (Knight, 2008:104).

‘the beau ideal of a light cavalry horse; strong, compact, hardy and temperate; and bearing the change to any climate without deteriorating.’

Valentine Baker (1858) cited in Anglesey 1975:437

British horses struggled immensely in Africa for many reasons, which led to the growing popularity of local horses. Firstly, horses had it tough onboard transports, conditions were cramped and unhygienic, and horses were often not given enough time to rest and acclimatise (Anglesey, 1986). Horses were forced to shed their coats quickly, with many dying because they were unable to do so (Anglesey, 1986:319). Most importantly, if a horse had survived the journey and was able to acclimatise, they were still highly susceptible to disease. Red-water and horse sickness were spread by ticks and insects that were endemic in many regions, such as Zululand (Knight, 2008:103). The mortality rate of horse sickness was 50%, and veterinary science could offer no cure at the time (Knight, 2008:103). It was for these reasons that the cape horse would become so popular.

These local horses did not have to undertake overseas transportation and were used to the climate. Therefore, they were able to be used immediately after purchase, rather than requiring a period of recovery. Moreover, they were less susceptible to disease, with many being ‘salted’ meaning they had previously been exposed to horse sickness or red-water, and they were now immune (Knight, 2008:104). These local horses were used to foraging for their food, and their smaller stocky build meant it was easier for them to move across the rocky, uneven terrain (Anglesey, 1986:341-342).

Aardvarks – the British Cavalry’s arch nemisis?

Traps set by aardvarks would prove problematic for British horses as they would create an uneven terrain scattered with large holes (Anglesey, 1986:341-342). These traps were created by aardvarks breaking open and digging up termite hills, leaving behind deep holes hidden in long grass (Knight, 2008:104) Aardvark image accessed from Wikimedia Commons

While the cape horse grew in popularity, the British cavalry still failed to learn their lessons regarding importing horses. During the Boer War, there was an unprecedented demand for remounts, as 300 horses were lost each day (Moore-Colyer, 1992:259). Therefore, thousands of remounts were required each month (Anglesey, 1986:322). Although there was a large horse population in South Africa, not all were suitable, with many being too small to carry a large British cavalryman (Badsey, 2007:89). This means that the British had to import horses from around the world. However, the British failed to act on knowledge regarding how to safely transport horses and failed to provide a reasonable rest time before entering the horses into active service. This led to huge amounts of horse wastage.

Many horses were shipped from one hemisphere to another, often arriving in African summer with full winter coats (Moore-Colyer, 1992:259-260). There was a shortage of horse clippers meaning horses could not be clipped off their winter coats; veterinary-surgeon Robert Pringle claimed he could have prevented 25% of deaths if he had been able to clip his patients (Anglesey, 1986:319). Horses were often not shod before being sent to work, meaning they were often lame within a few days (Anglesey, 1986:322). Transportation was long and horses were often delayed in ports, during such time horses lost much muscle and then struggled to carry the required weight of 20 stone (Anglesey, 1986:321). This led to horses quickly suffering sore backs and exhaustion (Anglesey, 1986:323.) despite both veterinarians and cavalry generals knowing that horses needed a minimum of a few months to a year to acclimatise, from years of experience importing horses to India, this was not acted upon (Anglesey, 1986:320). The reason for not giving horses enough rest time, was due to the ongoing war and lack of facilities to do so at ports. The lack of facilities to house these horses was accredited to the belief that the war would soon be over, but when it became clear the war was not going to be quick the system still did not change and horses were still not appropriately rested (Anglesey, 1986:321).

Out of the 4,170 cases of sickness only 163 were due to bullet wounds and three to shell fire (3.9%)

Horse illness in the Inniskilling Dragoon regiment cited in Anglesey, 1986:323

Lances, Sabres and Carbines

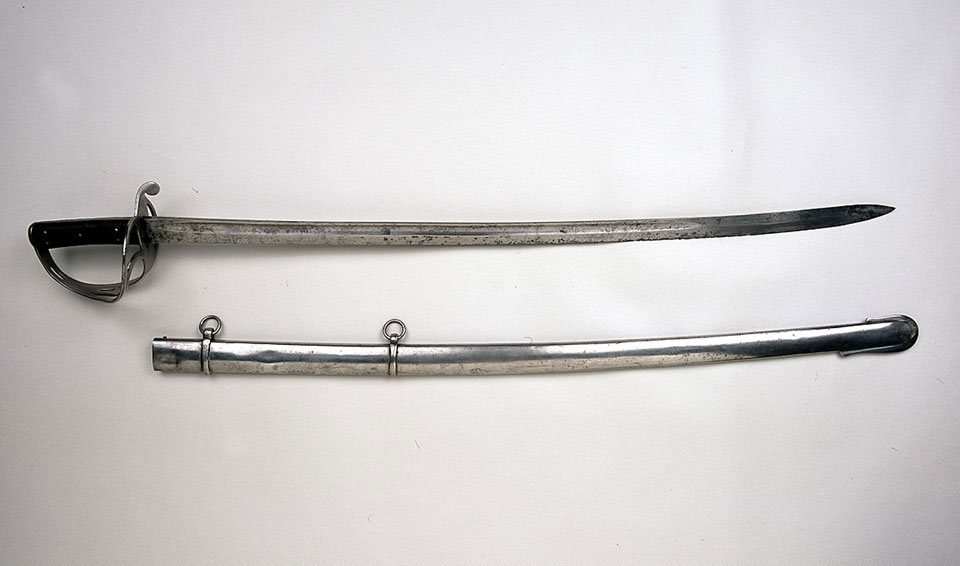

The British lance was a nine-foot weapon made of an ash or bamboo pole, with a head and shoe (Chappell, 2002:14). It was a weapon made for the charge, with the very sight of its lowered point engendering fear in the enemy (Brighton, 2004:15). It was a weapon strongly favoured by British cavalry hierarchy because of its longer reach and penetrative power (Brighton, 2004:15). However, its effectiveness was debated. Some believed the lance required too much skill and training to be wielded effectively, and thus too often its true potential was not realised (Anglesey, 1975:416). It did however prove effective when used by the front rank during a speedy charge (Anglesey, 1975:416). This was both because of its moral effect and that its longer reach could penetrate the enemy before they could launch a counter-attack with their sword (Anglesey, 1975:416 and Brighton, 2004:15).

Note: While the term ‘sabre’ refers to a curved bladed weapon, both ‘sword’ and ‘sabre’ were used often interchangeably.

In 1853 all cavalry were issued a new single universal pattern of sword (Chappell, 2002:14), previously the swords issued to the light and heavy cavalry differed from each other (Robson, 1968). This new Pattern 53’ sword was the same length as the old light cavalry pattern and possessed a slightly curved blade (Anglesey, 1975:409). Swords were housed in unlined steel scabbards, and every time the blade was withdrawn it blunted as the steel rubbed together (Brighton, 2004:3). Even the rattling of the sword against the steel scabbard could cause the blade to blunt, this led many cavalrymen to stuff the scabbard with straw to protect the blade (Brighton, 2004:14). In the following 75 years there were eight separate patterns of sword issued (Chappell, 2002:14), none seem to have introduced a lined scabbard. Furthermore, it took years for these new pattern swords to replace their predecessors; in fact, there is no evidence that the Pattern 53’ sword was used in the Crimean War (Anglesey, 1975:409-410). Little change to the sword occured during this period, and the cavalry proved slow at issuing the new universal pattern swords. The continued reliance on the sword and saber shows the British Cavalry’s reluctance to modernise and embrace newer technology.

A Cavalry Soilder ‘must trust his sword or lance alone for purposes either of offence or defence…The fire-arm is a weapon which can be used with effect only when he is acting on foot.’

Regulations for the Intruction and Movements of Cavalry, 1876:241 cited in Anglesey, 1975:420

The biggest change that occurred to cavalry weaponry during this period, was the introduction of the breech-loading carbine. The carbine was a short-barrelled, small-range version of the musket and rifle. Muzzle-loading carbines were ineffective and problematic. They had to be kept loaded, due to the difficulty of loading them while mounted, but would clog up if kept loaded in wet weather (Anglesey, 1975:418). None of the survivors of the Charge of the Light Brigade recalled using their carbines (Brighton, 2004:15), this is largely because they were awkward to use on horseback, heavy, and had a very limited range (Anglesey, 1975:418). Breech-loading solved the issues of loading on horseback (Chappell, 2002:15), however, it did not lead to an increase in their usage. A trooper was required to load, present, and fire his carbine one-handed while maintaining control over his horse (Anglesey, 1975:418); this required substantial skill and balance. Furthermore, cavalry officers favoured the lance and sabre, so there was limited training, and encouragement to use firearms. Despite little pressure to develop better weapons, several models of carbine were distributed to the cavalry in the period. The “monkey-tailed” carbine (American .451 calibre Westly Richards) was ordered and distributed in the 1860s (Anglesey, 1975:419 and Chappell, 2002:15). They were quickly replaced with more sophisticated models such as the Snider (Anglesey, 1975:419). Despite now being more accurate, easier to load, and lighter, they were still not used any more than the muzzle-loading carbines had been (Anglesey, 1975:419).

The Cardwell Reforms

The most significant changes that occurred to the British cavalry during the period 1853-1903 were the Cardwell Reforms. Catalysed by the shock of the army’s sufferance in Crimea, the Cardwell Reforms were a series of systematic changes implemented by Edward Cardwell who was appointed Secretary of State for War in 1868. The reforms would begin to shape the modern British army and went further than any previous changes (Tucker, 1963:110). Cardwell faced harsh opposition and yet he still managed to successfully pass three bills through Parliament (Hood, 2001:1). The Cardwell Reforms abolished dual authority, created a short-system service and abolished the purchase system.

Abolition of Dual Authority

Cardwell sped up the process of abolishing “dual authority.” The Duke of Cambridge, the Queen’s autocratic cousin, was the General Commander-in-chief of the army (Anglesey, 1982:30). Technically, the Commander-in-Chief should have been subordinate to the Secretary of State for War; however, due to the Duke’s social standing and close relationship with the Queen, the two offices were functioning with “dual control” over the military establishment. This meant that neither was subordinate nor independent of each other. Cardwell understood that this would have to change if he wished to implement reform, and in a memorandum presented to the Cabinet in January 1869 he forecasted that before any reform could take place, the Secretary of War had to be acknowledged as the final authority on all military matters (Dubs, 1966:36). Cardwell was able to persuade the Queen and the Duke of Cambridge, that the Commander-in-chief would be subordinate to the Secretary of State for War (Anglesey, 1982:30). In other words, Parliament technically now had sole control over the army.

Short-Service System

The enactment of the Short Service system aimed to resolve the problem of recruiting enough army reserves without using conscription (Anglesey, 1982:30). The 1870 Army Enlistment Act introduced a system of six years with the coloured regiments followed by six in reserves (Anglesey, 1982:31). For the cavalry it was eight years in the colours and four in the reserves, changing to seven and five years in 1881 (Anglesey, 1982:31). Six years’ service was deemed a reasonable amount of time to provide training and overseas service. Additionally, it would mean that a soldier would be young enough to find employment after his service was over (Tucker, 1963:131).

Short service did prove attractive, and recruitment increased throughout the 1880s (Tucker, 1963:133). By the Boer War, the short-service system was able to provide a reserve of eighty thousand men – although, there was a delay in mobilizing them (Tucker, 1963:141). This system replaced twelve years in the colours, after which soldiers could volunteer to join the reserves, which not many did (Anglesey, 1982:31). The system was successful in creating a larger reserve army, however it didn’t go far enough. The short-service system created an increased demand for recruits, as soldiers finished their service earlier (Anglesey, 1982:32). 6,200 recruits joined in 1862, while in 40,000 recruits joined in 1885 under the new system. On top of the increased demand for recruits, there was still a shortage of men required for war, and the Cardwell reforms didn’t increase the size of the army, nor did they improve the quality of training provided (Tucker, 1963:140). Overall, the short-service system did solve the problem of reserves in a non-conscript army, which was its main purpose. By the Boer War, it had produced a sizeable reservist force to aid the war effort. While the reforms didn’t go far enough, they were a very substantial start considering the lack of systematic change that had occurred previously.

Abolition of the Purchase of Officers’ Commissions

Another change the Cardwell Reforms implemented was the abolishment of the purchase system, through the Regulation of Forces Act 1871 (Anglesey, 1975:379). It took a while for the abolition to be put into place, partly because the Government was reluctant to replace a system that saved taxpayers’ money (Anglesey, 1975:379). Firstly, it didn’t mean that anyone could become a commissioned officer. An officer still needed a substantial amount of money, both to fit in socially and to be able to afford the additional costs. For instance, a non-commissioned sergeant-major entitled to a pension, paid 4s a day, with clothing, rations and education provided was often better off remaining as he was, than becoming a commission officer (Anglesey, 1975:382). This is because although a cornet was paid 8s a day, he was expected to pay for rations, uniforms, horses, accoutrements, and band subscriptions (Anglesey, 1975:382). Consequently, “in one regiment, a commission was offered to and declined by eight non-commissioned officers in succession” (Anglesey, 1975:382). Many argued against the system because it would enable the selection of officers from outside a regiment, which may destroy its camaraderie (Gallagher, 1975:333). On the other hand, it wasn’t uncommon for officers to change regiments, usually to avoid colonial service in India (Gallagher, 1975:333).

The abolition of the purchase system mirrored the social changes of the time, and acknowledged the rise of the middle class, who were now eligible to become officers in the army (Hood, 2001:2). The shorter service term appealed to the middle class and made becoming an officer an attractive career (Hood, 2001:3). The army needed more recruits, and by opening up more opportunities for middle-class men to become officers, they were more likely to get them.

Ultimately, the abolition of the purchase system did enable an all be it small, percentage of middle-class men to become officers (Gallagher, 1975:348). The quality of these officers didn’t improve much. This was in part because the abolition did not remove all of the bad officers, but moreover, training and standards didn’t improve (Tucker, 1963:140). Still not all officers had gone through formal staff college training, and they lacked initiative (Tucker, 1963:140). However, Cardwell had made a monumental step towards creating a modern army, one that more closely represented the Victorian social structure, by making it legally possible for men of other classes to become commissioned army officers.

Conclusion

Ultimately the British cavalry failed to embrace changes and suffered as a result. Firstly, the British cavalry did embrace the use of local Cape Horses. This was a reactive change, caused largely due to the deaths of British horses. Using cape horses was a positive change away from using aesthetic traditional breeds, towards using breeds more suitable for the environment. On the other hand, the cavalry failed to act on knowledge regarding importing horses, and consequently, thousands of horses died, which only exacerbated the demand for remounts. Cavalry officers were reluctant to change when it referred to weaponry, which meant the British cavalry entered the 20th Century still wielding swords. Despite little pressure to improve cavalry firearms, the British cavalry did update the carbines. Newer breech-loading carbines modernised the cavalry, but training did not change to model this. The focus remained on the lance and sabre, even in the face of Prussian horse artillery (Brighton, 2004:5). The cavalry appears reluctant to move on from their “Glory Days” of the previous century.

The Cardwell Reforms were significant changes that shows the British army were finally accepting the need for reform. Cardwell was met with much opposition, including the Duke of Cambridge, yet was still able to implement reforms and establish his authority as Secretary of State for War. The Reforms reflected social change and began to modernise the army and cavalry. The abolition of the purchase system enabled men of different classes to become officers, but more importantly, it began to ensure the quality of officers promoted within the cavalry. However, it would take a long time for its influence to be notable. It would take time for old officers to retire, and vacancies to open. Additionally, an officer still needed to have a substantial amount of money, so the system didn’t enable anyone to be an officer. While the Cardwell reforms did represent important changes, they didn’t go far enough. The cavalry that was deployed in the Boer War differed little from those who had fought in the Crimean War, almost 50 years previously. While the firearms had improved, and a large reserve army was available, the cavalry still suffered the same problems, because they had failed to adapt efficiently to the varied situations it found itself in, during the period 1853-1903.

Bibliography

Anglesey, G.C.H.V.P, Marquess of. (1975) A History of the British Cavalry: 1816-1919: Volume 2: 1851-1871. London: Leo Cooper LTD.

Anglesey, G.C.H.V.P, Marquess of. (1982) A History of the British Cavalry: 1816-1919: Volume 3: 1872-1898. London: Leo Cooper LTD.

Anglesey, G.C.H.V.P, Marquess of. (1986) A History of the British Cavalry: 1816-1919: Volume 4: 1899-1913. London: Leo Cooper LTD.

Badsey, S. (2007) ‘The Boer War (1899-1902) and British Cavalry Doctrine: A Re-Evaluation’. The Journal of Military History, Vol. 71, No. 1, pp. 75-97.

Brighton, T. (2004) Hell Riders. London: Penguin Books.

Chappell, M. (2002) British Cavalry Equipments 1800-1941, Revised edition. Wellingborough: Osprey.

Coventry, F.R. (2014) ‘Acrid Smoke and Horses’ Breath: The Adaptability of the British Cavalry’, Master’s thesis, Write State University. Available at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2404&context=etd_all [Accessed 15/12/2023]

Dubs, D.R. (1966) ‘Edward Cardwell and the reform of the British Army 1868-1874’, Master’s thesis, University of Nebraska at Omaha. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1399&context=studentwork [Accessed 01/01/2024]

Gallagher, T.F. (1975) ‘British Military Thinking and the Coming of the Franco-Prussian War.’ Military Affairs, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 19-22.

Gallagher, T.F. (1975) ”Cardwellian Mysteries’: The Fate of the British Army Regulation Bill, 1971′. The Historical Journal, Vol. 18, No.2, pp. 327-348.

Hood, D.F. (2001) ‘The Effects of the Cardwell Reforms on the British Victorian Army’, Master’s thesis, pp. 1-8, Californian State University. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/openview/5c88b50d896324b41b7e5f5b7cd4c692/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y [Accessed 01/01/2024]

Knight, I. (2008) Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military.

Moore-Colyer, R.J. (1992) ‘Horse Supply and the British Cavalry: A Review, 1066-1900’. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol. 70, No. 284, pp. 245-260.

Robson, B. (1968) ‘The British Cavalry Trooper’s Sword 1796-1853’. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol. 46, No. 186, pp. 106-109.

Tucker, A.V. (1963) ‘Army and Society in England 1870-1900: A Reassessment of the Cardwell Reforms’. Journal of British Studies, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 110-141.