Murals in Northern Ireland

The murals across Northern Ireland paint the picture of the country’s rich political history. The artists of the murals are often commissioned by communities to express their political views through art. Northern Ireland’s history of sectarian tensions and divide are evident across Belfast, with street murals visible in all areas of everyday life. The meanings behind the murals have therefore become a battleground for the different versions of history and political ideologies between both Republicans and Unionists. These murals highlight the social realities faced in the heart of each community and express the voice of the people at the time of their creation. They are often a symbolic representation of the activities of the time, to encourage a common social identity. In Northern Ireland these murals have been painted to enact social change for the last century, from Ulster Unionists strengthening an orange identity in 1908 to the anti-Brexit images of today. The murals paint the picture of these social movements and allow for a greater political voice and are thus able to strengthen communities and the causes they believe in.

The British Army in Northern Ireland

The representation of the British Army in Northern Irish murals starts with depictions of the Great War, most notably the battle of the Somme. World War I Irish battalions were made up of volunteers since the Irish weren’t subject to conscription (Gibney, 2017) therefore most of these murals are community based, celebrating the volunteers from each division. They focus on heroic depictions of soldiers alongside names of community members who have fallen in battle. During the battle of the Somme the Ulster division lost one third of their men (Gibney, 2017) and this loss is noticeable across Northern Ireland. The effects of the battles during the Great War were experienced in all communities with nationalists and unionists both suffering huge casualties and this feeling of loss is evident in the murals of the two world wars.

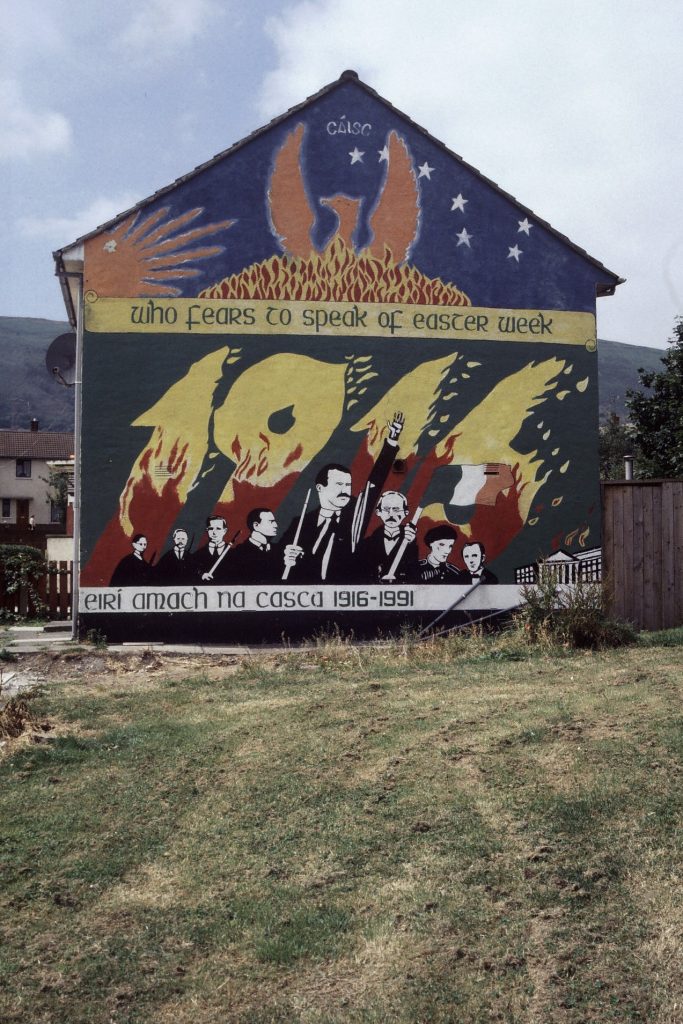

After the Somme, the Great War entered the streets of Northern Ireland in the form of the Easter rising. By April 1916 twenty thousand British Troops occupied the streets of Dublin (Gibney, 2017). This image of uprising against the British state resonates with many Republicans in Northern Ireland and therefore Easter Rising Murals within these community’s bear images of peace and colours of Ireland to show solidarity with the Irish rebels 100 years after the event took place.

The Irish war of Independence shortly followed the events of the Easter rising. From the creation of the IRA to the partition of Ireland, murals across Belfast depict images of the British Army’s involvement in the conflict through to the events of Bloody Sunday during the Troubles. The killing of thirteen unarmed protesters (McKittrick, 2021) by British troops, for some, marks the start of the troubles in Northern Ireland. Bloody Sunday became the face of distrust towards the British during the conflict as for many the events of Bloody Sunday demonstrated that the civil rights injustice was supported by all British Institutions including the army. The Bogside artist’s mural of this event thus sparked the start of depictions of Northern Irish (specifically Nationalist) hatred for the British Army. Sir John Peck stated that “Bloody Sunday had unleashed a wave of fury…hatred for the British Army had never been so intense…we are all IRA now” (Peck, 1978) The Republican Murals depicting bloody Sunday reflect this view by portraying the British Army as the aggressors and depicting civilians after violent attacks from army officials.

The rest of the troubles fill the streets of Northern Ireland with images of violence, peace, and community. Depictions of the British army are littered throughout portraying public views on their deployment and activity during the troubles. Since 1969 and the arrival of British Troops into Northern Ireland during the Troubles (McKittrick, 2012), political depictions of the British Army have been divided between Protestant and Catholic communities. The image of the British Army on the streets became the symbolic representation of the nation’s feelings towards the British Army and this differed across communities. The British Army is represented in murals of various conflicts, and the conflicts portrayed vary across communities. The difference in the army’s representations raises the question as to how on country’s military can be reacted to so differently across one nation. However, the stories written on the murals allow this question to be answered as each community’s identity was affected differently by the army’s presence.

Catholic Murals

Murals in Catholic areas naturally reflect Republican views and values. Their images celebrate Irish culture and symbols as well as focusing on interests and events that affect their communities. During the Troubles Catholic Murals were painted to advertise for the IRA, celebrate martyrs and commemorate victims of the violence (Alpha History, 2017). Arguably the most famous Catholic mural is the Shank hill road mural celebrating the efforts of Hunger striker Bobby Sands. Murals celebrating those actively working against the British state in hope of Irish Unity are common across Catholic communities. People working against home rule were celebrated by nationalists, institutions working alongside the British government were not. The British Army are painted negatively in Catholic community streets as they are seen as campaigning against the wants of nationalists during the Troubles.

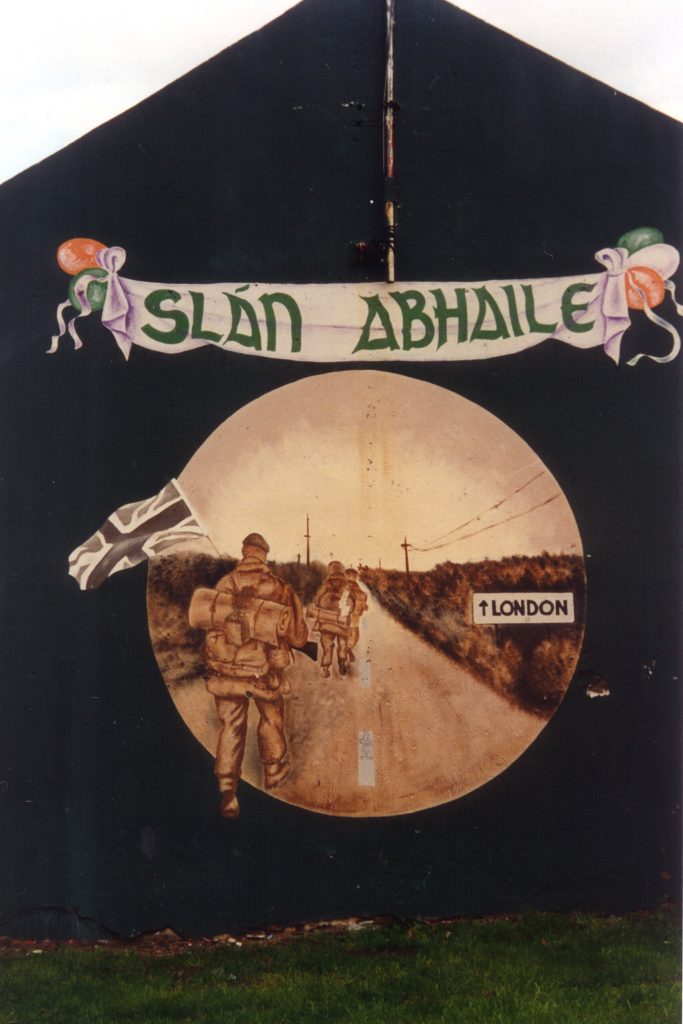

Traditional Irish symbols and culture such as the Irish language are often a common theme within Catholic murals. The mural below titled “Slain Abhaile” (Harris, 1995) uses this common Irish phrase alongside an image of the British Army returning to London at the end of the Troubles. Slain Abhaile literally translates to “Safe Home” and is an Irish phrase used in murals to bid farewell to the British Army. The use of these phrases within Catholic murals, depict the British Army as the other, and many murals, like this one, are advocating for their removal from Northern Ireland. The phrase ‘Fag Ar Sraideanna’ (Moloney, 1995) also features commonly in murals and translates to ‘leave the streets’ which further emphasises the Catholic viewpoint of ending home rule within Northern Ireland.

Contrary to the story on the murals, the entrance of the British Army into the Troubles was welcomed by Catholic communities (McKittrick, 2012) as an aid against the violence. However, after the events of Bloody Sunday in 1972, the British Army became the enemy and their representation came mainly in the form of images of violence, and memorials commemorating civilian lives lost to British Army violence. One focus of British Army depictions became their use of ‘plastic bullets’ after 17 people, mainly Children were victims of the army’s use of plastic/rubber bullets (Moloney, 1995). The British Army was thus seen as untrustworthy and dangerous. Many people stated that the British Army were “wanted for the murder of nationalist people” (Rolston, 2010). The murals reflected this viewpoint, with bold statements calling out British Army violence joined with images of guns and the machinery used to carry out these violent attacks.

In 1975, images of the British Army coupled with the British government started to surface. The British army was becoming tied to the decisions of Westminster as a British institution, run, and influenced by the British State. Events such as the Miami Show band Massacre in July (McKittrick, 2012), birthed questions surrounding collusion between these two institutions. Throughout the Troubles Catholics/ Nationalists were subject violence from institutions that were later found to have been colluding with the British Government, however, it wasn’t until this time that the collusion became evident to the public. Murals depicting this “state murder” (Miossec, 2007) reflected public concern. Some famous images include paintings of Margaret Thatcher, the British Army and traditionally British symbols surrounding gravestones of Catholics who fell victim to the violent results of this collusion.

Other events such as army attacks on women (Extramural Activity, 1970), were also preserved in the form of street murals. However, unlike the violent murals that focused on the actions of the British Army, images of Catholic resistance grew in popularity amongst mural artists (Vaughn, 2012). These murals demonstrated the strength of Catholic communities to rise against army attacks, so images of hope were painted to encourage and lift community spirits. Although the images of the army and artillery remained, images of catholic rebellion against the violence become the prominent focus of the messages in murals. The murals started to celebrate the efforts of Catholics/ nationalists against their oppressor. Catholic murals started to focus on the sustained effort of these communities. The focus switched from singular events to looking back at the years of resistance since Easter Rising of Irish people against the British state and consequently the British army.

The images of the British Army in Catholic murals have always been of violence. The messages presented and community viewpoints were what evolved over the troubles. Increasing public anger towards the army was prominent after Bloody Sunday to encourage paramilitary subscription and the resistance needed to influence Catholic resistance against British rule. Once accomplished, commemoration and celebration are often needed to increase community spirit, giving people a reason to continue with their efforts. This tactic was also used by the British Press during the Second World War to sustain the war effort. These murals thus reflect the need for communities to maintain hope to keep fighting against the violent attacks they were faced with during the Troubles. The British Army were thus the symbol of Catholic oppression and became the focus of most violence related murals within these communities.

Protestant Murals

Protestant murals represent the views of Unionist and contain traditional British symbols, institutions, and historical references. Protestant murals of the troubles focus on paramilitary symbols and the events of the U.D.F and U.V.F. Due to the British Army being a British Institution the feelings of Unionists towards the army were positive that those of Catholics. The nature of murals at the start of the troubles was to document the negative events and encourage people to join paramilitary groups. Images of the British Army were thus less prominent in Protestant communities. When visualised in murals, the British army is often commemorated for their efforts in conflicts of the past rather than focusing on their current presence in Northern Ireland.

One conflict painted on the streets of Protestant communities is the Battle of Boyne (1690). Images of the British Army and William of Orange alongside references to their presence in Scotland and Ireland can be seen in many areas across Unionist areas of Northern Ireland as an ode to the history of their orange identity. However, the Battle of Boyne is celebrated by Protestant communities as the victory of Protestantism over Catholicism (Lenihan, 2003). The symbolism in these murals therefore bears no homage to the British Army at the time and instead focus on the conflict of religion and identity. The unionist viewpoint on the British Army during the troubles was neither negative nor positive, the British Army is therefore seen as a British institution that forms part of their British Identity. Protestant mural depictions of the British Army are thus more historical in nature.

Historical murals often focus on specific events, most commonly the first and second world war. The images on these murals present the British Army as a heroic body. They proudly display British flags and celebrate the relationship between Northern Irish soldiers and the British Army (Alpha History, 2017). Many murals of the first and second world wars have written the phrase “For God and For Ulster” (Moloney, 2007) suggesting that the soldiers from Protestant communities are fighting for Northern Ireland rather than the United Kingdom. The murals depicting the British Army often take a more local focus. The murals celebrate the efforts of the army in images of VE Day street parties, these images aid a positive rhetoric around the actions of the British Army. However, in response to the violent images within Catholic murals many Protestant murals are painted to defend British military symbols such as the Poppy. Phrases such as “offensive to all those who wear the poppy” (Rolston, 2003) converse with negative murals with the purpose of neutralising the British army in the troubles debate.

Protestant murals overall take a more historical approach in their representation of the British Army. Using a heroic lens to picture past conflicts Protestant murals feature traditional British institutions to highlight their connection to their British identity. These murals stand as reminders of how community members fought alongside the British army from the Battle of Boyne to the two world wars. Although this dominates the depictions of the British army, the political nature of the conflict means that some murals were painted in response to murals in Catholic communities, defending Unionist British identity through the image of the British military.

The Peace Process

Since the signing of the Peace Agreement in 1998, the Northern Irish government has injected £3.5 million into the changing of the murals (Vaughn, 2012) Alongside this, arts committees have been created to approve mural paintings before they go onto the streets. The government sees this change as an opportunity for communities to find new identities (Vaughn, 2012) and move away from the militaristic identity of the past. Historical murals have become the voice of this change. Many Loyalist mural artists have replaced paramilitary murals with images of the first and second world war. This redirection has been driven by the lack of need to represent paramilitary gunmen anymore. Instead encouraging community members to remember and commemorate those who fought for Ulster has become the focus today. To aid the peace process the creation of murals has become about celebrating issues that united people rather than divided them.

Although an attempt to remove violent images has become an integral part of Northern Ireland’s peace process, the political nature of the murals has remained. Murals focusing on outside conflicts such as the Israel Palestine conflict and south African Apartheid (Rolston, 2003) reflect the political views and demonstrate solidarity from the people of Northern Ireland. Murals against the Peace Agreement have also surfaced since, the loyalist mural “Nothing about us, without us, is for us”(Lovito, 2014) reflect their anger towards the current situation. The growth of political murals has identified that the changes to the murals are not absolute nor permanent and many people view this as “a reminder that sectarianism is not dead and that the peace process many are not forever” (Alpha History, 2017) UK politics is also covered in the murals, demonstrating both Unionist and Republican views on British current affairs. Events such as Brexit, general elections and the pandemic all interpret the thoughts and feelings each community and evidence Northern Ireland’s struggle for peace since the signing of the peace treaty.

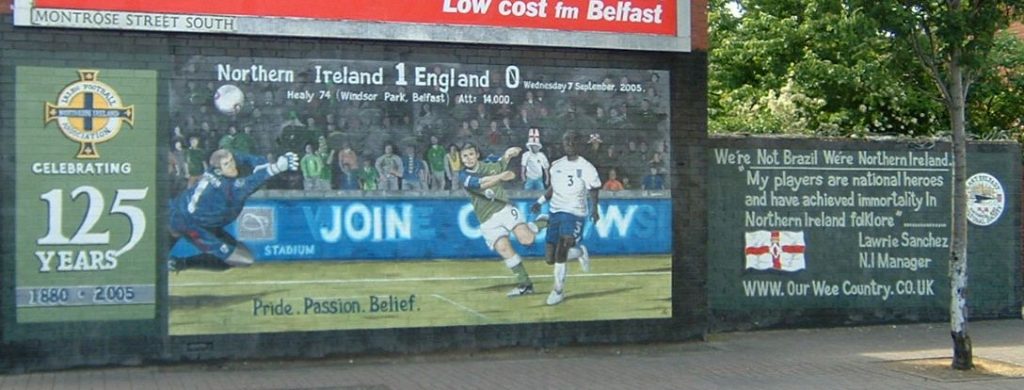

The Peace Process in Northern Ireland has thus seen a change in the perspectives as to the purpose of the murals. The lack of necessity to display violence has been made apparent with both community members and mural artists alike. The promotion of peace and integration has become the priority. While politics remain, images of guns have been painted over with pop culture references and sports teams, to allow people to evolve from the conflict and focus on the post Belfast Agreement Northern Ireland.

Brexit

The Anti-British rule rhetoric has re-entered the political scene in Northern Ireland since the Brexit referendum in 2016. Many Republicans believe that Brexit has reopened the Irish Unity debate (McCann, 2017, since Northern Ireland voted with a majority to remain within the European Union (BBC News, 2016). In terms of the political representation of this view, the murals have become centred around the growing distrust for the British state. Violent murals and images of paramilitary groups have emerged in large numbers since the referendum and even more so since the UK’s official exit in 2020. These murals have appeared in response to the trade agreement and the border in the Irish sea (PEACEMAKER,2021). This response has come from all communities, conversing with each other about the prospect of a return to violence. The images on the murals reflect this fear. As well as images of paramilitary groups, memorials for people affected by the rise in tensions such as Journalist Lyra McKee (The Irish Times, 2019) have also started to resurface, similarly, though in much smaller quantities, to during the troubles.

Although images of violence have re-entered the focus of murals, images of the British Army have not. The current events opening the united Ireland debate are not linked to the activities of the British Army. The representation of the army is therefore only relevant in Northern Ireland if they are present in the street. Without the exposure of the army in people’s everyday lives the army just become a symbol of opposition or identity, depending on political ideology. An effort has been made to move away from this divided view by mural artists to promote a common voice moving forward politically and socially in Northern Ireland. The representation of the British Army is therefore likely to diminish even further as they are no longer involved in the current affairs of the Westminster in Northern Ireland.

Conclusions

Northern Irish Street murals present a political image of the country’s 100-year history. Since the start of the troubles to the peace process the murals have evolved from being an art of conflict to an art of peace. In terms of the British Army’s representation the sectarian divide between Protestant and Catholic communities’ evidence a division in the image of the army within the murals. In Catholic communities, the distrust of the British state and hatred of home-rule manifested into violent anti-army paintings. Protestant communities on the other hand view the British Army as an institution that represents their British heritage. The British army appears in celebratory and commemorative historical murals. However, since the peace process efforts have been made to remove the images of violence from the streets to promote unity across communities. However, the political nature of the murals has remained and thus images of gunmen reappear at times of rising tensions. The Brexit referendum has become a catalyst for this re-emergence. The reopening of the Irish Unity debate has brought back feelings of hope from many nationalist communities. Violence, although to a lesser extent, has appeared back on the streets and thus back into the murals. However, even with the growth of paramilitary, arms, and violence back into the murals since the Brexit referendum the British Army have not seen a return. It can therefore be argued that they are just a symbol for political views and values. The representation of the British Army in murals across Northern Ireland can thus be seen as symbolic in nature rather than an accurate representation of the thoughts and feeling of the people towards the institution throughout the countries 100-year history.

References

Alpha History (2017) Northern Ireland Murals. Available at: https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/northern-ireland-murals/

BBC News (2016) EU referendum results. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/politics/eu_referendum/results

Cooley, K. 2007 An Ulster Volunteers/UVF mural in Bangor [Online] [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murals_in_Northern_Ireland#/media/File:Kilclief_flats.jpg

Extramural Activity. 2012 Falls Curfew 1970 [Online] [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at: https://extramuralactivity.com/2012/08/

Extramural Activity. 2018 Unfinished Revolution [Online] [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at: https://extramuralactivity.com/2019/01/31/unfinished-revolution/

Ferrier, D. (2019) The Border: The Legacy of a century of Anglo-Irish Politics. London: Profile Books Ltd

Gibney, J. (2017) A Short History of Ireland 1500-2000 London: Yale University Press

Goldstein, R., 2012. Bordering in Belfast: Peace Lines and Wall Murals.

Harris, J. 1995 A mural in Short Strand saying “Slan Abhaile” or “Safe Home” to British Troops [Online] [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murals_in_Northern_Ireland#/media/File:Unidentified_irish_mural.jpg

Kennedy‐Pipe, Caroline, and Colin McInnes. “The British army in Northern Ireland 1969–1972: From policing to counter‐terror.” The Journal of Strategic Studies 20.2 (1997): 1-24.

Kwekubo, 2006. Bobby Sands Mural in Belfast [Online] [Accessed: 09.01.2022] Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bobby_sands_mural_in_belfast320.jpg

Lenihan, Padraig (2003). 1690 Battle of the Boyne. Tempus. pp. 258–259.

Lovito, M. 2014 Loyalist in Belfast mural critical of the Good Friday Agreement [Online] [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murals_in_Northern_Ireland#/media/File:Nothing_with_us.jpg

McCann, G. and Hainsworth, P., 2017. Brexit and Northern Ireland: The 2016 referendum on the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union. Irish Political Studies, 32(2), pp.327-342.

McKittrick, D & McVea, M. (2012) Making Sense of the Troubles: A History of the Northern Ireland Conflict, London: Penguin Books

Miossec, 2007 Ardoyne, North Belfast Collusion is not an illusion [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Collusion_is_not_an_illusion.jpg#/media/File:Collusion_is_not_an_illusion.jpg

Miossec, 2007. A mural in Belfast depicting the Easter Rising of 1916 [Online] [Accessed: 09.01.2022] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murals_in_Northern_Ireland#/media/File:Easter_1916.jpg

Miossec, 2007. A mural in Belfast showing solidarity with the Portadown Orangemen [Online] [Accessed: 09.01.2022] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murals_in_Northern_Ireland#/media/File:Drumcree.jpg

Miossec, 2007 Ulster Volunteers mural in Belfast, Online] [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f3/Old_Dundonald_Road.jpg

Moloney, P 2007. UVF For God And Ulster [Online] [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at: https://petermoloneycollection.wordpress.com/2007/08/31/uvf-for-god-and-ulster-3/

Moloney, P. 1995. Fag Ar Sraideanna [Online] [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at:https://petermoloneycollection.wordpress.com/1995/01/26/fag-ar-sraideanna/

Moloney, P. 1995. Remember the victims of Plastic Bullets [Online] [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at: https://petermoloneycollection.wordpress.com/1995/03/03/remember-the-victims-of-plastic-bullets/

PEACEMAKER, 2021. Good Friday Agreement negotiators call for NI Protocol suspension

Peck, J. (1978) Dublin from Downing St. London:

Rolston, B., 2003. Changing the political landscape: murals and transition in Northern Ireland. Irish Studies Review, 11(1), pp.3-16.

Rolston, B., 2010. ‘Trying to reach the future through the past’: Murals and memory in Northern Ireland. Crime, Media, Culture, 6(3), pp.285-307.

Ruffles, K. 2016 Bloody Sunday Mural, [Online] [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bloody_Sunday_mural_-_panoramio.jpg#/media/File:Bloody_Sunday_mural_-_panoramio.jpg

The Irish Times (2019) Mural tribute to Lyra McKee appears in Belfast Available at: https://www.irishnews.com/news/northernirelandnews/2019/05/07/news/mural-tribute-to-lyra-mckee-appears-in-belfast-1614051/

The Miami Show band Massacre, 2019 [TV Documentary], Netflix

Vincent Vaughn (2012) ‘Art of Conflict: Northern Ireland’, [TV Documentary], Netflix

Wiki Commons, 2006. Northern Ireland association football team mural [Online] [Accessed: 08.01.2022] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murals_in_Northern_Ireland#/media/File:NI_murals_NI_football.jpg