“If the tanks succeed, then victory follows.”

– General Heinz Guderian, 1937.[1]

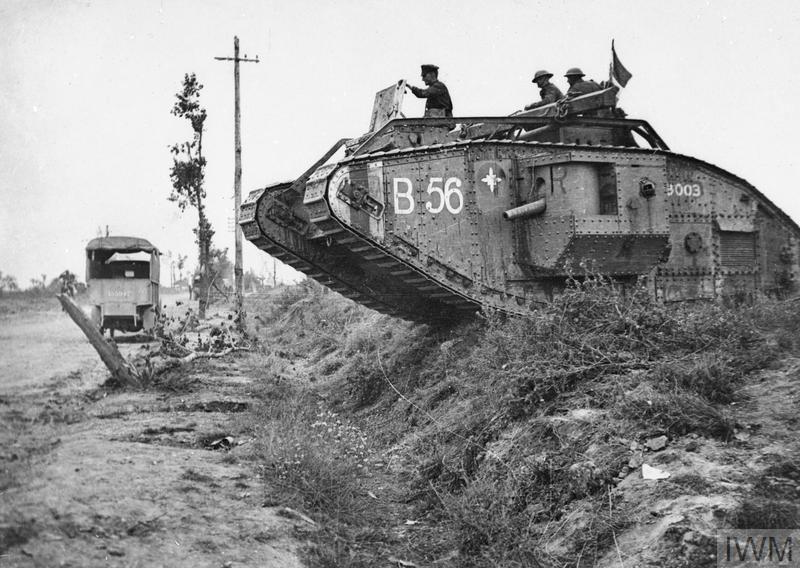

During the First World War, Britain was the first country to develop and field a new weapon that would revolutionise warfare: the tank, with the most famous design being the Landship. Tanks would be utilised to great effect by Britain and its allies from 1916 onwards to break the deadlock of trench warfare for good, bringing mobility back to the battlefield.

By 1918, Britain was victorious. The British Army and its armoured forces seemed to be standing at the forefront of armoured warfare development and tank design, unmatched by either friend or foe.

By 1939, this was clearly no longer the case.

The outbreak of the Second World War and the rapid defeat the Allies would suffer in France in 1940 at the hands of Nazi Germany would come as a shock to the British Army. The defeat highlighted the deep-seated issues within the British military’s understanding of the new realities of warfare. Chief amongst these issues was the British Army’s views on tank doctrine and design; the incredible success of Germany’s Panzer divisions in carrying out swift attacks against British troops and tanks highlighted how far behind Britain’s armoured forces had fallen, and the need for reform was made clear.

The Second World War and the new realities of armoured warfare would pose an immense challenge to Britain and its armoured fighting forces. Facing an opposing force that had made substantial developments in both how a tank should be designed and how it should be utilised as a tool of warfare, British tanks would undergo a steep learning process across multiple, diverse theatres.

From the fields of France and the deserts of North Africa, to the mountains of Italy and all the way to the heart of Germany, British tanks faced great trials and learnt harsh lessons. But by the end of the war, Britain’s armoured forces had overcome these challenges and learnt key lessons in developing the tank concept further, with the armoured forces of 1945 a far cry from what they had been in 1939.

This page will document this learning process, covering the development of Britain’s tank designs and armoured forces over the course of the Second World War, the challenges they faced, and otherwise providing a look into the experiences and struggles of an oft-forgotten section of the British Army in World War II – from its status as a technologically-backwards and inexperienced force at the outbreak of the war, to the innovative and well-developed arm of the British Army it would become by the end of the war.

The Interwar Period and Britain’s Rearmament

“The tank was a freak. The circumstances which called it into existence were exceptional and are not likely to recur. If they do, they can be dealt with by other means.”

– Major-General Sir Louis Jackson, 1919.[2]

Despite the value of the tank as a concept being made clear by the success of Allied tank assaults during WWI, the British Army seemed reluctant and, in some cases, almost hostile to the idea of developing their armoured forces further once the war ended. Traditional military thinkers in the British Military seemed to reject the idea of elevating the role of the tank to anything above a support tool for the infantry. Despite having used tank offensives to remarkable success himself, Field Marshal Douglas Haig demonstrated these sentimants by stating that, “It should never be forgotten however that weapons of this character [such as tanks] are incapable of effecive independent action … their real function being to assist the infantry to get to grips with their opponents.”[3]

The tank was clearly seen as nothing more than a tool for a war that had now finished. With the British Cabinet implementing the ‘Ten Year Rule’ that decided Britain would not involve itself with another major war for 10 years,[4] military expenditure dropped. The Tank Corps was left understaffed and undermanned, with little money or interest being diverted their way in the immediate aftermath of the Great War beyond the Tank Corps being made a permanent part of the British Army in 1923, though limited to only 4 divisions.[5]

Actual development in Britain’s armoured forces only really began to take off towards the end of the 1920s, but with lingering reluctance from the Army and the Treasury. In 1926 the Tank Corps were authorised to order a new design from Vickers (who had primarily manufactured machine guns during the war); the design, the A1E1 ‘Independent’, was a notable improvement over anything the British had made prior, but only 1 was ever made due to concerns over the cost.[6] In the following year, the Experimental Mechanised Force (EMF) was established under Field Marshal George Milne to try and develop the idea of armoured warfare further. Field exercises putting tank brigades alongside cavalry and infantry aimed to try and discern how best to utilise the tank as a formal part of the armed forces.

The lessons learnt were valuable ones indeed, helping to demonstrate the possibilities of the tank as a main part of an attack, rather than just a support tool for the infantry. Military theorists such as J.F.C Fuller and Basil Liddell-Hart would also be key in developing ideas of mobile warfare in general, arguing for the use of tanks as the main driving force for an attack to break through enemy lines and use their speed and firepower to wreak havoc.

The British Army, though interested enough by the results of what the EMF had done to pursue further tank development, did not adopt the ideas of Fuller or Liddell-Hart for a number of reasons: the primary, material reason was that tank production was already a costly endeavour, and the need for a large armoured force inherent to Fuller and Liddell-Hart’s theories would necessitate even more spending at a time where British military spending was heavily restricted. The other major reason was less to do with anything material, and more to do with the fact that neither Fuller nor Liddell-Hart were particularly popular with British military leadership: Fuller clashed with his superiors once he was allowed to assist the EMF in its first major exercise (the Eastland v Westland Exercise of 1927) and was subsequently sidelined from further tank development,[7] whilst Liddell-Hart and his ideas were hated by high-ranking officers within the British military (such as General Cyril Deverall, then Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and Field Marshal Henry Pownall, who would be Chief of Staff for the BEF during the Battle of France in 1940).[8]

(Image provided by Wikimedia Commons)

(Image provided by Wikimedia Commons)

The 1930s marked a period of rearmament for the British Military, as the British cabinet opted to revoke the Ten Year Rule in response to international political developments; the first development being Imperial Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931, and the second, more pressing concern, being Adolf Hitler’s consolidation of power in Germany in 1933.[9] With the full push for rearmament in 1937 came increased budgets for the Army, allowing the development of new tanks to try and modernise the Tank Corps (which were redesignated as the Royal Armoured Corps) further.

However, the speed and armour specifications the British military demanded for their new medium tank were simply unfeasible; the proposed models were either suitably fast but lacking the required armour, or vice-versa.[10] In light of these issues it was decided then that rather than produce a “perfect” medium tank, British tank design and production for vehicles intended for direct combat would instead be split into one of two main categories:[11]

- Infantry Tanks: prioritising armour over mobility, these were slow but powerful models designed to assist infantry in breaking through enemy lines.

- Cruiser Tanks: Prioritising mobility over armour, these swift models would follow up on breakthroughs made by the infantry and their tanks to move quickly behind enemy lines, based on how cavalry units were previously used (leading to tanks of this type sometimes being called Cavalry Tanks).

Ideally this arrangement would allow for the vehicles to be specialised for either speed or armour and be assigned to different units for different purposes. However, because British rearmament prioritised the Navy and the Air Force (for both were deemed to be key to any potential defence of Britain and its overseas imperial holdings), tank development did not receive the attention and funding it needed to effectively rearm by 1939, with tank production remaining limited as a result.

The beginning of the Second World War would bring the failings of Britain’s tank forces to light and demonstrate the harsh reality that the British Army wasn’t prepared to fight an armoured war.

The Early War in France: Britain’s Initial Failure

© IWM (F 3178)

“We followed the brigadier’s car back to Calais. As we pulled away, Billy nodded towards three bundles covered by groundsheets. Boots stuck out from under them.

‘Who are they?’

I couldn’t say. As they were from tank crews we must both have known them: nearly all of them had been at Lydd.

‘What’ll happen to them?’

I wasn’t sure. We’d never practised burying the dead during exercises on Salisbury Plain.“

– An excerpt from the memoirs of Major William Close,

describing his tank unit’s evacuation from France in 1940.[12]

The experience of British tank crews in France was far from pleasant. Against the Germans, Britain’s tank forces were simply ill-prepared for armoured warfare, with a slew of factors hindering the performance of British tank divisions in France.

The first, and most glaring issues, were the designs of the tanks being fielded and the number of them available. Due to the limitations that British tank production initially faced most of the tank models being used were older, obsolete models, as a lack of funding and time meant that better tank models were not available in sufficient numbers yet. The majority of Britain’s armoured force being sent into France consisted of ‘tankettes’ or light tank models like the Mark VI light tanks, which were poorly armed (its main armament consisted of just a machine gun) and lacked protection against anything more impactful than a rifle round. The rest was made up of severely limited numbers of infantry and cruiser tanks; by September 1939, only 143 tanks of both types were available.[13]

Of these slightly more substantial infantry and cruiser tanks, most were designs like the A9 (Cruiser Mk I) and A11 (Infantry Mk I ‘Matilda I’) that were less than ideal for use in France. Both were lightly armoured for starters, making them vulnerable to German anti-tank guns and Panzers, and both were lacking in firepower (the A9 at least had a 2-pounder cannon that could engage enemy tanks; the Matilda I on the other hand sported just a machine gun).

Some designs stood out in terms of their quality, such the Matilda II infantry tank. The video above, provided by the British Tank Museum in Bovington, talks in greater detail about the specific strengths and weaknesses of the Matilda II. In it, it is shown that the tank’s primary strength was its armour; able to resist the most powerful gun the Germans were fitting to their tanks at the time (a 37mm cannon), Matilda IIs were a glaring roadblock for German troops whenever they were encountered. Also mentioned is the astonishing action conducted on the 21st May 1940, in which around 18 Matilda II tanks were used to great success in a counterattack against advancing German tank divisions near Arras. The resilience of the Matilda II’s armour against German tank cannons caused a panic amongst the German crews that required the presence of their commanding officer, General Erwin Rommel, to calm them down and devise a means of defeating the British Matilda IIs encountered. This effort by the British tanks at Arras proved to be crucial in giving the soldiers at Dunkirk more time to evacuate.

However, because British tank production was initially slow and had only begun to ramp up by the time war broke out, the Matilda II was not manufactured in large enough quantities to make a serious impact on the outcome of the Battle of France. For instance, at the start of the war in 1939 only 2 Matilda IIs had been completed.[14] When the British Expeditionary Force was shipped to France, they were supposed to be equipped with 50 Matilda IIs; only 23 could be provided for the conflict.[15] None of the Matildas returned to Britain: If they hadn’t been destroyed by enemy action then the rest had been purposefully abandoned, either due to a lack of replacement parts to fix them when they broke down (a common problem for British tank crews at the time) or abandoned and destroyed by their own crews to prevent their capture by the Germans during the evacuation of Allied troops from France.

The evacuation of Allied troops from France was a disaster for the British Army and especially for its tank regiments; practically every armoured vehicle that had been sent to France had to be left there. Yet there was no time to rest for the Royal Armoured Corps, as they were due to be shipped to a new theatre of war that would serve as a real challenge to British tank design and doctrine: the North Africa Campaign.

The North African Campaign: A Dangerous Learning Experience

“We regarded the advent of our new tanks with a great deal more vital interest than a newly-married couple inspecting their first home. We were also fascinated by the group of American Army technicians who came with them.“

– Major Robert Crisp, describing his reaction to the arrival of new M3 Stuart light tanks provided by American lend-lease in 1941.[16]

The entry of Italy into the war and the surrender of France in 1940 meant that it would only be a matter of time before Britain’s colonial holdings in Africa – including the vitally-important Suez Canal – would be threatened by the Axis. Many of the tank regiments that had been evacuated from France were soon sent to North Africa to assist in the coming North African Campaigns, with any tanks that could be spared being sent along with them.

This meant that for most of the early campaign in North Africa, British armoured forces were still using designs like the Mk VI light tank and the Matilda II. Though still effective against Italian tanks (Italy’s tank production would remain limited and inferior for the entire war), the arrival of the German Afrika Korps in early 1941 would mean the arrival of more imposing tank models and more effective anti-tank guns (particularly the high velocity 88mm anti-aircraft gun), both of which would soon prove to be a major danger to British tanks.

The German models of tanks being fielded, including the Panzer III (which had served in France) and the new Panzer IV, were soon sporting thicker armour and larger guns that allowed them to shrug off the increasingly inadequate British 2-pdr gun and outrange the British on the open plains of the African desert. With the focus of British tank production now on producing as many tanks as possible, the 2-pdr would nonetheless remain in service until 1942,[17] and new cruiser tank designs were produced and shipped out despite noticeable flaws in their design.

One of these designs, the A13 Crusader, would become a defining part of British tank warfare in the North Africa Campaign. As explained in the video, the Crusader was a flawed vehicle. It was cramped, prone to overheating in the desert heat and woefully under-armed, with the early Mk I and II models still using the 2-pdr gun. Many Crusaders were even shipped without proper testing to ensure they worked.[18] Despite these flaws however, the Crusader was used in large numbers in North Africa by the British, where the mobility and the sheer number of Crusader tanks available encouraged their use in operations against the Axis, such as the aptly-named Operation Crusader in 1941.

A defining issue for British tanks during this period was still the insufficient firepower provided by the 2-pdr gun and the reliability issues present with designs like the Crusader. Until the Crusader could be refitted with the more powerful 6-pounder gun and the new 17-pounder gun could be finalised, British tank crews would receive a stopgap solution in the form of American lend-lease, with the arrival of American M3 Lee medium tanks in late 1941.

American lend-lease was vital for the British in North Africa. The M3 Lee (modified versions to fit a British radio were called ‘Grants’) was equipped with a 75mm main cannon that was more than capable of combatting the German Panzer IIIs and IVs that had been causing issues for British tank crews. Major Bill Close of the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment noted that the crews of these tanks were very pleased, writing: “The Grant crews found their new tank and armourment ideal and we looked forward to meeting the panzers more or less on even terms.”[19]

American tank models would serve alongside British Matilda, Crusader and Valentine tanks for the rest of the North African Campaign, providing a vital boost to the stockpile of tanks available to British crews. The M3 would eventually be replaced by the American M4 Sherman – a key Allied tank in the war – in 1942, with British crews quickly switching over to the more effective Sherman.

Beside providing extra tanks for British tank crews, the arrival of American lend-lease equipment gave British tank production some breathing room for the rest of the campaign. When the Allies had finally pushed the Axis out of Africa in 1943 and the invasion of Italy raged, British tank production had finally started to equip some previous designs with more powerful weaponry. Importantly, when time came for the invasion of France, Britain would finally have some effective tank designs ready to deploy for the campaign ahead.

Normandy and Beyond: British Tanks Back on Track

“But the key to success in battle is not merely to provide tanks, and guns, and other equipment. Of course we want good tanks, and good guns; but what really matters is the man inside the tank, and the man behind the gun.”

– Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, March 1944.[20]

When Allied troops landed at Normandy during D-Day, British tanks would soon come to join them to assist in breaking out from the beach. By this stage British tank production was producing better guns in order to deal with increasingly dangerous tanks – like the Panther and the Tiger – that Germany was fielding in France. While most British tanks were still reliant on the 6-pdr gun, the 17-pdr and 75mm guns were now available and capable of taking out whatever heavy armour the Germans could field; for this reason the 17-pdr and 75mm guns were mounted on British tanks whever possible, such as the Sherman Firefly and the Churchill.

The Firefly was a means of providing extra firepower to British tank crews while making use of the large stocks of reliable Sherman tanks that Britain had received from the Americans. Fireflies would be relied upon to deal with enemy armour that the other Shermans and British tanks could not penetrate, providing an extra degree of flexibility and offensive capability to British tank squadrons.

The Churchill infantry tank was a bit of an oddity, with design elements like the shape of its tracks being more akin to WWI designs, but it was an incredibly resilient model that had been built with the expectation that it would punch through the toughest defences the Germans could throw at it.[21] Able to even survive shots from the German 88mm, traverse almost all obstacles in its path and fitted with a powerful 75mm gun in the models that served in North-Western Europe, the Churchill was well-suited to the British Army’s demands.

Accompanying these two models in 1944 was the British Cromwell cruiser tank, which represented a marked improvement in British cruiser design. The Cromwell was well-suited to armoured warfare; it was highly mobile, reasonably armoured, and reliable, with an effective 75mm cannon that was good enough for anti-tank and anti-infantry combat. In the words of David Fletcher, “It set a standard and provided a tank that well-trained crews could rely upon.”[22]

The Cromwell was to serve with the British for the rest of the war but would also serve as the basis for an improved model of tank, which would go on to inspire a major development in tank design. This successor to the Cromwell was called the Comet.

The Comet came very late in the war, first arriving on the Western Front in March 1945 and seeing only limited service,[23] but it was an effective design. As discussed in the video above, the Comet was developed due to the Cromwell’s turret being too small to mount a high-velocity anti-tank cannon. The Comets came equipped with the 77mm (though that wasn’t what it was chambered for) high-velocity gun, capable of defeating German heavy tanks like the Panther with ease.[24] Still fast, thanks to using the same engine as the Cromwell, and equipped with effective armour, the Comet was a very successful design that began to blur the lines between the characteristics of infantry and cruiser tanks.

Conclusions and Reflections

The Second World War had been a wake-up call for Britain’s military in many ways, and its tank corps had been no exception. A lack of proper, dedicated development and funding during the 1920s and early 1930s had laid the foundations for failure in 1940, but the result of Britain’s initial armour failures was necessary in order to shock British military leadership out of the complacency it had adopted since the end of the First World War.

Each new theatre of war that British tank crews found themselves fighting in was a harsh but invaluable learning experience, a means by which Britain learnt what their tanks and crews needed to wage a modern war. Rigid adherence to the concept of employing distinct cruiser and infantry designs began to lessen over the course of the war, the guns and armour needed for effective tank designs became more readily available with the development of British wartime industry, and the loosening on design restrictions just prior to Operation Overlord and the invasion of Nazi-occupied France allowed British tank design to finally adapt to the developing state of the war.

By the end of the war in 1945, British tank design had clawed its way back to being innovative from the outdated status it had found itself in at the outbreak of war in 1939: The Comet would lead to the development of the Main Battle Tank (MBT) concept – a tank design that could fulfil the roles of multiple tank types simultaneously – in the form of the Centurion. Powerful, well-armoured and mobile, the Centurion would remain in British service until the mid-1960s, demonstrating the value of the new MBT concept.

The concept of the MBT has since become the norm for current militaries, serving as the template for how modern tanks should be designed and utilised – a concept that, in part, can owe its origins to the successful development of British tanks in the Second World War.

Citations

[1] Guderian, H. Panzer Leader (New York, Da Capo Press, 1996), p.43. Available at: Internet Archive [Accessed 31 December 2021]

[2] Geoffrey, R. The Past Times Book of Military Blunders (London, Guinness Publishing, 1999), p.152. Available at: Internet Archive [Accessed 31 December 2021]

[3] Boraston, J. H. Sir Douglas Haig’s Despatches, Dec. 1915 – April 1919 (New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1927), p.300, cited in Cavaleri, D. P. ‘British Tradition vs. German Innovation’, in Armor, 106 (1997), p.63. Available at: Google Play Books [Accessed 1 January 2022]

[4] Coombs, B. British Tank Production and the War Economy, 1934-1945 (London, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013), p. 7. Available at: Google Books [Accessed 1 January 2022]

[5] Smithers, A. J. Rude Mechanicals: An Account of Tank Maturity during the Second World War (Barnsley, Pen and Sword Publishing, 1989), p.29. Available at: Google Books [Accessed 1 January 2022]

[6] Ibid. p.34

[7] Smithers, A. J. A New Excalibur: The Development of the Tank 1909-1939 (London, Grafton Books, 1988), p.247. Available at: Internet Archive [Accessed 22 March 2022]

[8] Ibid. p.264

[9] Beale, P. Death by Design: British Tank Development in the Second World War (Cheltenham, The History Press, 2016), pp.21-22. Available at: Google Books [Accessed 2 January 2022]

[10] Harris, J. P. Men, Ideas and Tanks: British Military Thought and Armoured Forces, 1903-1939, (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1995), p.240

[11] Ibid. p.241

[12] Close, Bill. Tank Commander: From the Fall of France to the Defeat of Germany: The Memoirs of Bill Close (Philadelphia, Casemate Publishers, 2013), p.14. Available at: Google Books [Accessed 3 January 2022]

[13] Imperial War Museum, Britain’s Struggle To Build Effective Tanks During The Second World War. Available at: The Imperial War Museum [Accessed 3 January 2022]

[14] Beale, P. Death by Design, p.108

[15] Fletcher, D. British Battle Tanks: British-Made Tanks of World War II (London, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017), p.14. Available at: Google Books [Accessed 3 January]

[16] Crisp, R. Brazen Chariots: A Tank Commander in Operation Crusader (New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 2005), p.14

[17] Imperial War Museum, Britain’s Struggle

[18] Smithers, A. J. Rude Mechanicals, p.115

[19] Close, B. Tank Commander, p.77

[20] Montgomery, B. L. The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Montgomery, (New York, New American Library, 1959), p.207. Available at: Internet Archive [Accessed 6 January 2022]

[21] Fletcher, D. British Battle Tanks, p.152

[22] Fletcher, D. British Battle Tanks, p.242

[23] Beale, P. Death by Design, p.176

[24] Smithers, A. J. Rude Mechanicals, p.319

Bibliography

Beale, P. Death by Design: British Tank Development in the Second World War (Cheltenham, The History Press, 2016). Available at: Google Books [Accessed 2 January 2022]

Cavaleri, D. P. ‘British Tradition vs. German Innovation’, in Armor, 106 (1997), pp.63-65. Available at: Google Books [Accessed 1 January 2022]

Close, Bill. Tank Commander: From the Fall of France to the Defeat of Germany: The Memoirs of Bill Close (Philadelphia, Casemate Publishers, 2013). Available at: Google Books [Accessed 3 January 2022]

Coombs, B. British Tank Production and the War Economy, 1934-1945 (London, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013). Available at: Google Books [Accessed 1 January 2022]

Crisp, R. Brazen Chariots: A Tank Commander in Operation Crusader (New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 2005)

Fletcher, D. British Battle Tanks: British-Made Tanks of World War II (London, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017). Available at: Google Books [Accessed 3 January]

Geoffrey, R. The Past Times Book of Military Blunders (London, Guinness Publishing, 1999). Available at: Internet Archive [Accessed 31 December 2021]

Guderian, H. Panzer Leader (New York, Da Capo Press, 1996). Available at: Internet Archive [Accessed 31 December 2021]

Harris, J. P. Men, Ideas and Tanks: British Military Thought and Armoured Forces, 1903-1939, (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1995)

Imperial War Museum, Britain’s Struggle To Build Effective Tanks During The Second World War. Available at: The Imperial War Museum [Accessed 3 January 2022]

Montgomery, B. L. The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Montgomery, (New York, New American Library, 1959). Available at: Internet Archive [Accessed 6 January 2022]

Smithers, A. J. A New Excalibur: the Development of the Tank 1909-1939 (London, Grafton Books, 1988). Available at: Internet Archive [Accessed 22 March 2022]

Smithers, A. J. Rude Mechanicals: An Account of Tank Maturity during the Second World War (Barnsley, Pen and Sword Publishing, 1989). Available at: Google Books [Accessed 1 January 2022]