How were the fine arts in Britain shaped by the Great War?

‘Aesthetes Vs Philistines’

The outbreak of the First World War witnessed innumerable change in all facets of state, politics, society, culture and economy. One of those, the British world of Fine arts, was no exception. ‘Total War’ grasped entire nations in a unified effort to prevail victorious. In that strife, what really mattered came under scrutiny and the arts was one of many victims. From 1914, the Fine Arts in Britain went under a transformative period. The redirection of material, social and moral capital towards the war effort seemed, at first, to cause serious damage to the Arts. Artists had their reputation and moral fibre tarnished, art institutions were on the brink of financial ruin and social obscurity, and markets all but seemed to disappear. However, akin to many sectors of state, the Arts responded by mobilising itself along with the general war effort. As Result, the Arts were left in a relatively stronger position within British society than before the outbreak of war. Public engagement with the arts became more widespread, the Avant-Garde and modernists received more appreciation from all classes, and the government engaged with the arts on an unprecedented scale. The key factors behind this change were the work of art institutions, artists and the unique time and conditions the onset of the worlds bloodiest war yet. The Imagery that was produced would have a lasting impression of Britain’s conceptualisation of the First World War, with the institutions and ideas borne of this phenomenon continuing today, over one-hundred years later.

Britain had a peculiar relationship with the arts when compared to her European contemporaries and was largely uninterested in the ‘progressive’ movements. Its proponent actors inhabited an, albeit large, yet relatively walled-off community of thousands of artists, dealers, organisations, museums and critics.[1] In Britain, the general public and the fine arts industry alike were at odds with one another in many respects.[2] Prevailing established styles were dismissive of the modernists and avant-garde, the modernists by nature were dismissive of ‘old’ styles, and the public largely saw it all as the idle and frivolous pursuit of the wealthy.[3] Similarly, the art world looked down upon the public as unable to fully appreciate the gravity and subtleties of the endeavour. Clive Bell, in 1914, wrote in the Bloomsbury Aesthetics publication, Art:

‘In the face of the present international situation, we must expect that for a time interest in art and the history of art is likely to give place to more violent claims on the attention of the public. We feel it to be none the less of the utmost importance, at such a time, to keep alive those disinterested activities which are the distinguishing mark of civilization. Even though the appeal that art makes is feebler than the more pressing demands of self-presevation, it is more persistent and more enduring.’

[4]

Here, Bell calls for the continuation of mutual disinterest between the public and fine art spheres in Britain, as a form of protection against the widening rift the war may cause. More importantly so, his quote outlines the relative disconnect between Britain’s arts and the public – indicating to the notion of an ‘elite club’. However, the enduring aspect of art was going to be secured through completely different means to what Bell suggests, with greater enrolment and attention to the general public and their temperament.

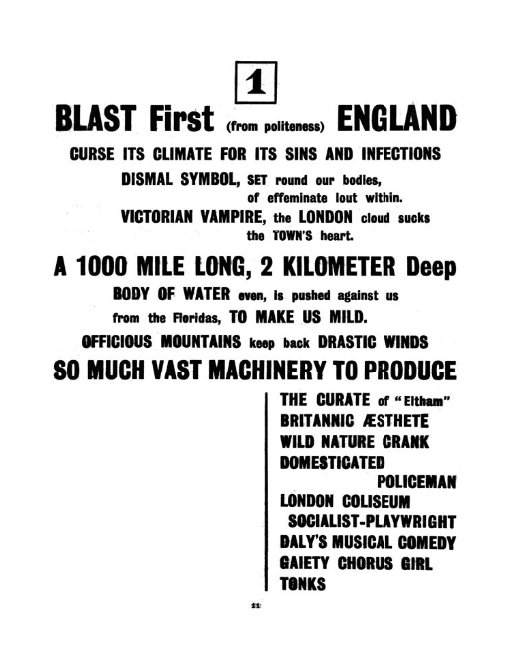

The war forced the arts to engage with the war effort – As the war effort threatened the feasibility of Britain’s artistic culture to survive in its current form. Wyndham Lewis, who would go on to be a celebrated official war artist, stated in his Vorticist publication that his movement had absolutely ‘nothing to do with “The People”.’[5] Yet after the war, his remarks would significantly alter – in his 1919 book titled The Caliph’s Design, he states his intent to release art into ‘the general life of the community’.[6]It is clear that something significant had changed, as for an avant-garde artist of Lewis’ ilk[7] could not have made such a U-turn without both his and the wider publics’ understanding on the value of art in society changing.

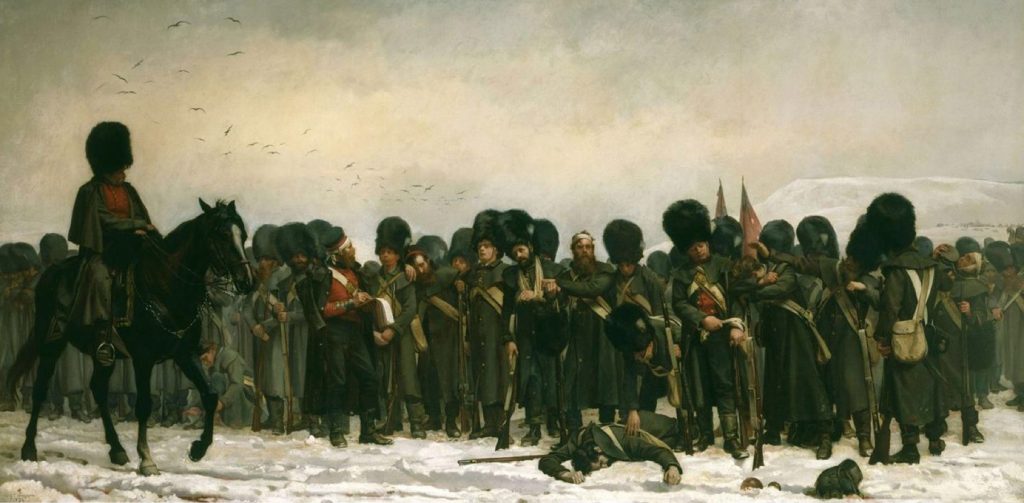

There had been many competing voices as for the general impact of war on art, and whilst scholars and artists alike drew conclusions based on history before the First World War, the results of this war would have truly divergent properties to the ones before. This was an industrial war, mechanised by rail, fought by entire nations mobilising to output as much military muscle as they could afford. The battlespace, the numbers, the casualties and the weapons were remarkably new and similarly lethal.[8] Whilst on one hand, the violence and excitement of the war would seem to offer artistic opportunities – traditionalists argued that many of history’s greatest works were made in war,[9] whilst modernists like R. W Nevinson declared ‘This war will be a violent incentive to Futurism, for we believe there is no beauty except in strife, and no masterpiece without aggressiveness.’[10] Others rightfully saw the impending danger the destructive capability that modern weapons posed towards sites of artistic significance, such as the German bombing of the Cathedral of Reims in Belgium. The Director of the National Gallery wrote: ‘War is no longer waged with arrows and lances, or tardy muskets, but carried on both on earth and in the air with high explosives that blow to atoms all that they strike, and strike haphazard from afar.’[11] The speculation from the inhabitants of the art world in Britain certainly were mentally provoked by the war, yet the direction it would steer them would be more profound still.

‘Fiddling Whilst Rome Burns’

Within months into the war, dealerships, auctioneers, galleries, societies, clubs, movements and artists saw a decline in interest, money and public support for the arts.[12] The War effort, as proclaimed by the general public and the government, did not consider the art establishment to be of any value during wartime. In fact, it went further than that, with some instances of it being accused of undermining, even purposefully disrupting the war effort.

The initial problems for Britain’s wartime arts sector were primarily financial. ‘All museums, galleries &c, should be closed to the public forthwith and placed at the disposal of the Government’.[13] It was thought to be a valuable lesson in economy, that would characterise a national belt-tightening, where those sectors of economy deemed unvaluable to the war effort, the nation could go without. Government purchasing grants, which had previously been offered to the likes of the National Gallery were revoked.[14] Art societies saw a steep decline in membership as many associates deferred attention to national service, probably being quite conscious of their public image of ‘doing their bit’,[15] rather than pursuing something even the government deemed unjustified. Sales and exhibitions also plummeted, as either institutions hibernated, liquidated or moved business. Within three weeks of war, the Duveen brothers (A well-renowned old-masters trader) moved their business to the USA, where the market for luxuries had not been diminished.

The same can be said for the artists themselves. William Orpen, who would also go on to be a celebrated official war artist, had turned over eight-thousand pounds in 1913, and by the middle of the war that figure had dropped to five-hundred.[16] The Board of trade reported that artists were amongst the worst hit of the professional classes and the War Relief Council stated that by the end of 1915, artist as claimants represented 8.8% – second only to musicians at 9%.[17] Yet what was more remarkable was the social limitation that war had placed upon Britain’s artists, as war gripped the country, so too did a fever of suspicion emboldened by nationalism. Not only could they receive an adequate amount of money for their work, but also, conditions were that they found it difficult to work at all.

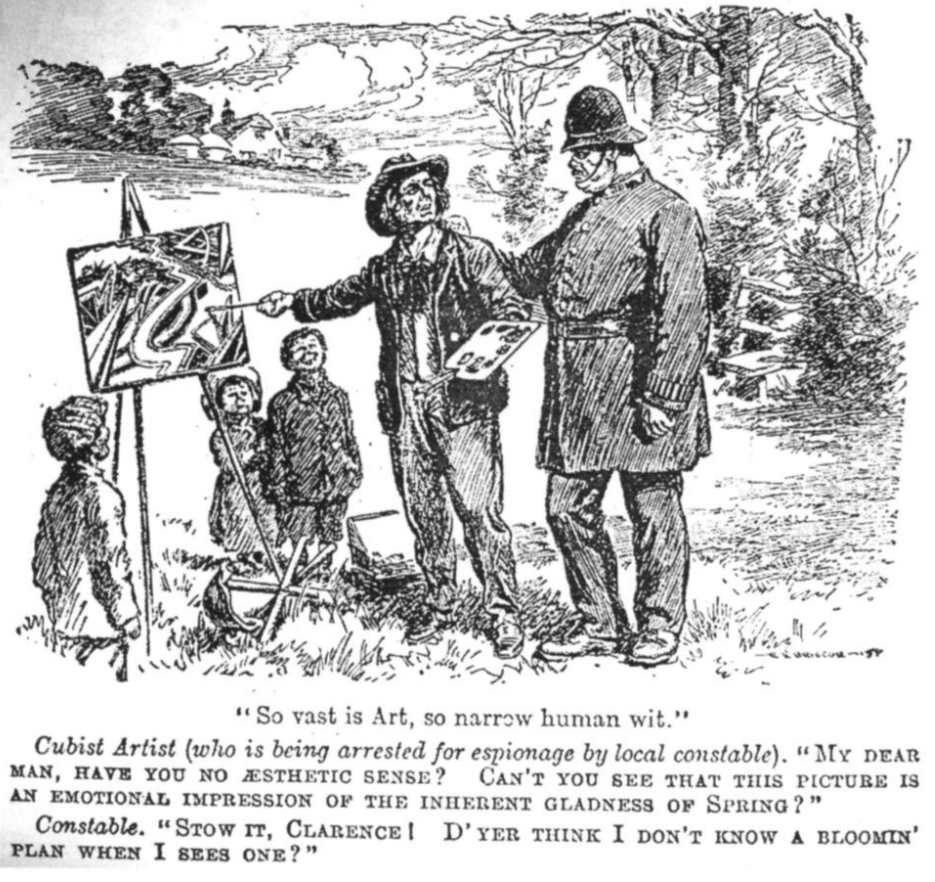

‘Traitor Painters’,[18] the title of James Fox’s journal article outlines the ways in which fears of spying activity bled into a suspicion of artists and their work. The idea of spies in wartime had been publicised by writers in the decades proceeding the war, however the explicit link between artists and spies was made by Robert Baden-Powell’s My Adventures as a Spy. He details how artists could employ their ability to encode sensitive military intelligence into seemingly innocuous imagery.[19] What legally permitted artists to be persecuted was the Defence of The Realm Act (DORA), which along with aims of acquiring the social and material capital needed for security, also possessed this clause:

‘No person shall without the permission of the competent naval or military authority make any photograph, sketch, plan, model, or other representation of any naval or military work, or of any dock or harbour, or with intent to assist the enemy, of any other place or thing’

[20]

There were hundreds of cases of artists being arrested, interrogated and interned by the police – often tipped by the suspicious public.[21] The highest profile of these was Philip de László’s arrest. A Hungarian by birth, he had international training and eventually settled in London, where he would paint portraiture of high-calibre figures in British society as a naturalised British Subject. Such was his correspondence with family in Hungary, his financial transactions, and his origin of birth that authorities sort it right to intern him. The case was shrouded in xenophobic prangs and claims of fabricated evidence – however he was released after having to prove his prevailing ‘Britishness’.[22]

Not only did artists find it hard to make money during wartime, but they were also similarly prevented in making works by a collection of public sentiment and governing legislation.[23] It was based upon claims that the artistic world not only was a drain on national resource, but also a potentially harmful facet to the general war effort. However, the British arts would not be bogged down by such claims and would subsequently alter themselves in order to mobilise with the nation. An endeavour to prove that the arts could be a national asset in wartime.

‘The Arts Mobilise!’

The British arts sought to reaffirm their purpose and patriotism towards the war effort through charitable schemes – aimed at elevating their economic and social standing through making themselves central to the war effort. Huge public demand for the images of war, and the military warming to the idea of art being a key propaganda device gave artists opportunities – furthermore – the use of artistic techniques in wartime practice were becoming more apparent to military policy-makers. As result, modernism would be propelled into general acceptance and capitalise upon the Imagery of the Great War, whilst the nation became more artistically inclined, with a newfound importance for its role in wider society. The product of this artistic mobilisation was arguably the greatest act of state patronage in modern British history to date[24].

Art Institutions around Britain were working to funnel the wealth of the rich into the war effort. The Royal Academy staged ‘The War Relief Exhibition’ in early 1915, where large portions of the proceeds would go to the Red Cross.[25] The auction house, Christies, had been approached by the Red Cross in order to flog its donations – Christies offered its services free of charge – and by the end of the war had helped raise approximately £400,000.[26] Museums began a wide array of displays aimed at instructing, rallying and recruiting the public into the War effort and by 1916, Wellington House (the Institute behind the British war propaganda effort) used these exhibitions to circulate its pictorial propaganda campaign – containing drawings made by Muirhead Bone, the first Official War Artist.[27]

There was huge public demand for images concerning the war. The urge was satiated by numerous old and new forms of media – from the written word to the cinema. Photography was also becoming readily available to the masses. In competition with other media, the war artists sought to produce images of qualities that other formats could not achieve.[28] This had two distinct effects, one, the art produced would be more modern and radical than any other military art before it. Two, such art would inhabit a new societal and cultural significance, where the nation would have a sharpened awareness for the different capacities of media.[29]

‘Appearance is not reality. Appearance may be observed, but reality, to be known, must be experienced. That is why the report of the official artist has more value than the report of the official photographer. For the Camera observes everything and experiences nothing. It is inhumanly impartial and canot speak the language of the spirit. Concerning the things that we most wish to know is dumb. We ask for the truth, the whole truth, and it gives us nothing but facts.’

[30]

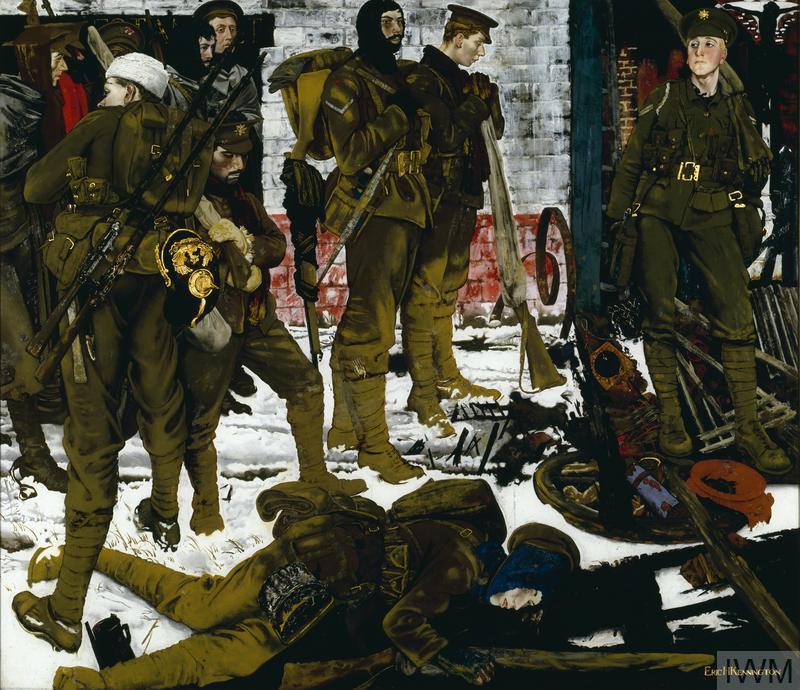

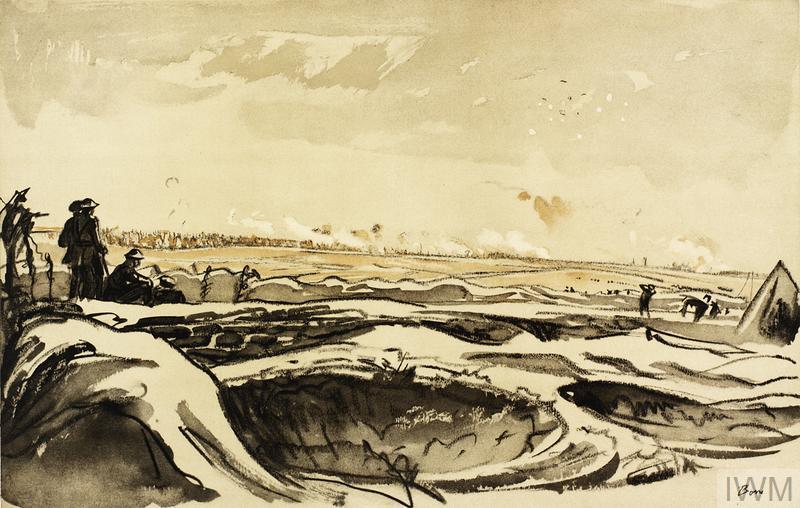

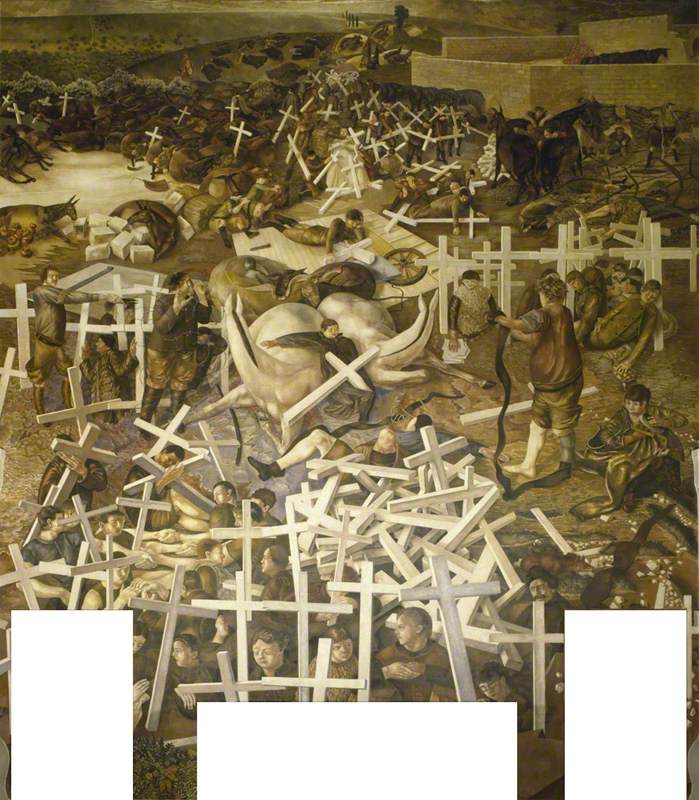

The ‘Official’ War Artist was the product of a chance encounter, Charles F.G Masterman, the director of Wellington House, was approached and informed that Muirhead Bone – a famed Scottish etcher – had been called into service. Asking whether his talents are better used regarding his unique ability for Art?[31] [32] At first, Wellington House’s prerogative was simply propaganda. However, as the scheme enlarged – taking on new artists, exhibiting works on in the aforementioned relief exhibitions, and subsequent rapturous public applause – the scheme evolved into a ‘record’ phase, and then lastly a ‘memorial’ phase under the direction of the newly established Imperial War Museum (IWM). This transformation was undoubtedly the work of the artists themselves, as younger and often soldier-artists took to the ‘official’ brush, their work lent to a first-hand depiction of which the jarring consequences of modern war held. This is evident if one was to trace the very first official war art to that of the end of the war, Bone was a pedant for detail, whereas the artists the followed: Nevinson, Lewis, Orpen and Nash (to name a few) applied their pre-war experimentation to the western front. Partly in a bid to distance themselves from other media, partly self-promotion and even in some instances service-dodging,[33] the official war artists bought modernist ideas into their works and produced a collection of a plethora of styles, all inhabiting the same subject genre. When the IWM presented these works together after the war, it was arguably the first time an exhibition held paintings of such stylistic difference yet receiving extremely positive support from critics, social elite and all other classes alike.[33] Through this example we can see how from the outbreak of war, the arts were dismissed as unimportant, yet come to the close of war, it had become an indispensable part of the nation’s war effort. Post-war art sales boomed, breaking many pre-war records and the government began work on introducing legislation that reassessed the importance of the arts in education – a newfound appreciation for artistic expression as direct consequence of the war.[35]

The lasting impression this transformative period in the fine arts has held heavy in Britain. It arguably enabled a greater admiration for the avant-garde, a segue to the slew of world-renowned artists and movements from Britain heralded for their unique vision: Francis Bacon, Henry Moore, and the YBA (Young British Artists) such as Damien Hurst and Tracey Emin; to name but a few. Furthermore, the IWM has thrived and expanded since its inception. If one were to visit IWM London, they would be greeted with the same collection of remarkable images created by the Official War Artists – yet now they also inhabit large posters publicising the museum, books and textbooks on the First World War, keychains, posters and calendars.[36] the IWM has used such art to capitalise upon the public image of the Great War, and as one of the key institutions in the education of Britain’s wartime involvement, it has made a lasting and unique contribution to the nation’s historical and artistic identity. It is hard to dismiss that without the unique conditions of total modern war, the nation-wide self-assessment of what really is important in wartime would not have occurred. However, as it did – the fine arts stepped up to the challenge presented the nation its credibility and purpose, aiding in the remarkable identity of British creativity and self-image in wartime.

A Short Visual Guide to European War Art (Early Renaissance – Modernist), Primarily British.

Citations

[1] Fox, J. British Art and the First World War 1914-1924, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 11-13.

[2] Hynes, S. A War Imagined: The First World War and English Culture, (London, Pimlico, 2011), pp. 22-25.

[3] Gough, P. A terrible Beauty, British Artists in the First World War, (Bristol, Sansom & Company, 2010), pp. 18-21.

[4] Bell, C. ‘Special Notice’, Burlington Magazine 25 (September 1914), p. 325.

[5] Lewis, W. The Caliph’s Design: Architects! Where is Your Vortex? (London, Egoist Press, 1919), p.7.

[6] Lewis, W. ‘Long Live the Vortex!’, BLAST: Review of the Great English Vortex 1, (1914), p.7.

[7] Farrell, J. ‘World War I and the Visual Arts’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 75:2 (2017), pp. 12-13.

[8] Black, J. The Age of Total War, 1860-1945, (Plymouth, Rowman & Littlefield, 2006), pp. 14-21.

[9] Fox, J. British Art and the First World War 1914-1924, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 14.

[10] Spaulding, F. British Art Since 1900 (London, Thames & Hudson, 1989), p. 58.

[11] Holmes, C. ‘Notes’, Burlington Magazine 25 (September 1914), p. 366.

[12] Fox, J. British Art and the First World War 1914-1924, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 22-41.

[13] Committee on Public Retrenchment, ‘Third Report of the Committee on Retrenchment in the Public Expenditure’, Cd.8180 (1916), in Reports for Commissioners, Inspectors and Others, 1916, vol. XV, pp. 177-180.

[14] Fox, J. British Art and the First World War 1914-1924, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 23.

[15] Thacker, T. British Culture and the First World War: Experience, Representation and Memory (London, Bloomsbury, 2014), pp. 54-55.

[16] Fox, J. British Art and the First World War 1914-1924, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 35.

[17] Annual Report, Professional Classes Aid Council, 1914-15, pp. 20-1. Found in: Fox, J. British Art and the First World War 1914-1924, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 37.

[18] Fox, J. ‘Traitor Painters’, The British Art Journal, 9:3 (2009), pp. 62-68.

[19] Baden-Powell, R. My Adventures as a Spy, (London, 1915), p.53.

[20] Rimington, A.W. ‘Painting Out of Doors in War Time’, Imperial Arts League Journal (1916), p6. Found in: Fox, J. ‘Traitor Painters’, The British Art Journal, 9:3 (2009), pp. 62-68.

[21] Fox, J. ‘Traitor Painters’, The British Art Journal, 9:3 (2009), p. 65.

[22] MacDonogh G. ‘Philip de László in the Great War’, The De Laszlo Archive Trust, (2017). URL: https://www.delaszlocatalogueraisonne.com/de-laszlo/the-great-war

[23] Gough, P. A terrible Beauty, British Artists in the First World War, (Bristol, Sansom & Company, 2010), p. 35.

[24] Fox, J. British Art and the First World War 1914-1924, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 99.

[25] Royal Academy of Arts, War Relief Exhibition in aid of the Red Cross and St. John Ambulance Society and the Artist’s General Benevolent Institution, 8 January 1915 – 27 February 1915. URL: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/exhibition-catalogue/1915-war-relief-exhibition-in-aid-of-the-red-cross-and-st-john-ambulance

[26] Fox, J. British Art and the First World War 1914-1924, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 74.

[27] Gough, P. A terrible Beauty, British Artists in the First World War, (Bristol, Sansom & Company, 2010), p. 51.

[28] Paret, P. Imagined Battles: Reflections of War in European Art, (Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press), p. 83.

[29] Fox, J. British Art and the First World War 1914-1924, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 100.

[30] Nevinson, C. R. W. & J. E. Crawford Flitch. The Great War, Fourth Year. (London, G. Richards, 1918.) p. 7. URL: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015035307415&view=1up&seq=13&skin=2021

[31] Gough, P. A terrible Beauty, British Artists in the First World War, (Bristol, Sansom & Company, 2010), p. 23.

[32] Hynes, S. A War Imagined: The First World War and English Culture, (London, Pimlico, 2011), p. 249.

[33]Gough, P. A terrible Beauty, British Artists in the First World War, (Bristol, Sansom & Company, 2010), p. 33.

[34] Fox, J. British Art and the First World War 1914-1924, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 144-146.

[35] Ibid. p. 148-9.

[36] A remark based upon my own frequent visits to the many IWM museums around Britain.

This is a very well-constructed piece of literature and I will definitely book mark 🙂 very pog very interesting. Your teachers must be very proud to have taught such an informed gentleman.