Whistles blow along a 15-mile front as over 170,000 men pour out of their trenches into No Man’s Land,[1] in what was to become the bloodiest day in British military history. But what ideas lead to this offensive and what would later be learnt to allow for the victory of the allies?

The First World War is a conflict that has been written about and analysed by many historians, especially due to the recent 100-year anniversary. Which allows for new ideas and theories to be put forward.

That’s why it’s interesting to look over ideas such as tactics and their wider perceptions with the help of hindsight and understanding of the conflict. The Battle of the Somme in 1916 is one of the most well-known events of WW1 and there are already many pre-existing ideas about the tactical choices made which is why it is such an important topic to look at in more depth.

Before the Somme

To start to understand the tactical changes that were made after the Somme there needs to be an explanation of what choices were made before the battle in 1916. This includes the differences in army size and training as well as the differences in attacking styles.

At the start of the First World War Britain had a small professional army known as the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), of this force four infantry divisions and five cavalry units were sent to Belgium in August of 1914- about 55,000 men that were then joined by Indian colonial soldiers bringing the total to 86, 000 by December of 1914.[1

This was tiny compared to the German standing army of around 700,000 men that after just a week of mobilisation had grown to 3.8 million.[2] This was because Germany used conscription to get all available men into the armed forces, but this wasn’t something that Britain introduced until 1916.[3]

This is because conscription was not something that was seen as politically acceptable in Britain as Gordan Corrigan explains that it was seen as a very extreme last resort and public opinion often resided in the idea that the Royal Navy was the most important defence force for Britain, so conscription to the land army wasn’t necessary.[4] This meant that any soldiers sent over to Belgium and France- after the initial wave of the BEF- had to be volunteers.

Conscription was still politically unacceptable, and the men would have to be volunteers’

Gordon Corrigan

This is very significant when looking at how the generals in the British Infantry were approaching the War as there was not enough professionally trained soldiers for a long, drawn-out conflict that the First World War ended up as.

Because the British generals were preparing for a quick conflict, tactics such as large cavalry charges were still seen as a good choice for how to attack the enemy forces. An example of this was the first combat experienced by the BEF at the Battle of Mons on the 23rd of August, where there was a large cavalry charge that was successful at breaking up sections of the German infantry.[1]

What this shows is that the cavalry was not entirely useless in the early months of the war, as some people may think, and before the dug in trench system and stalemate they were actually very useful as an attacking force even if the battle resulted in an allied retreat.[2]

The Battle of the Marne

‘A sergeant irritated everyone who could hear him by continually shouting out: ‘Stick it, lads. We’re making history’

Corporal Bernard Denore, September 1914.

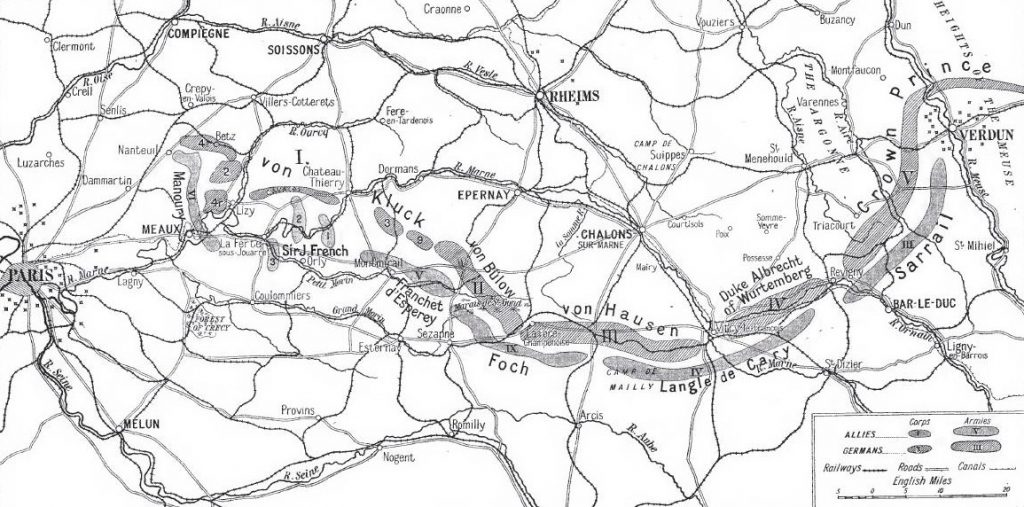

One interesting battle to look at is the First Battle of the Marne that was fought from the 6th to the 12th of September in 1914, it was the French army and BEF that were facing the Germans after they had crossed though Belgium and into France.[1] This battle was successful at stopping the rapid German advances that had almost reached Paris- as was the goal of the Schlieffen Plan (a plan that aimed for a rapid invasion of France and Russia).

It is also significant as the result of the battle caused the ‘race to the sea’ where both the allies and German soldiers were rushing to outflank each other up to the coastline of the North Sea.[2] Which would see the implementation of dug in trenches and a stalemate- two of the most important tactical difficulties that had to be overcome by the British infantry.

What this shows is that although the British Infantry wasn’t fully prepared for the modern style of conflict that would be seen a few months down the line, the skills and tactical intelligence of the BEF is not something to be dismissed or overlooked. It is something to be taken into consideration when approaching battles such as the Somme in 1916 and the end of the war in 1918 to see how the tactics changed or were scrapped altogether.

Patrick Scrivenor states that the Battle of the Marne was ‘not only the most decisive European battle since Waterloo; it was also Europe’s biggest and most costly battle to date’.[3] This is due to the combined allied soldiers sustaining over 200,000 casualties and deaths, with the German total expected to be much higher. This is significant in understanding the changing perceptions to what the war was going to be and challenged the commonly held idea that the war was going to be quick and well and truly finished before Christmas.

‘Most decisive battle since Waterloo, Europe’s biggest and most costly battle to date, losses on this scale had never been seen before- it was an augury of what was to come’

Patrick Scrivenor, The Dictionary of Battles.

Was it only Britain who was struggling with a new style of warfare?

While it may seem that many historians place the sole blame of a lack of preparation on the British generals, the events of 1915 show that this was an issue on both sides. For example, the large German offensive in the Second Battle of Ypres from the 22nd April to the 25th of May was designed to use the advantage of attacking after releasing chlorine gas but the German army didn’t have enough resources to fully break through so it was considered in hindsight a massive failure. Especially because by the time they chose to use it again many of the allied troops had begun to improvise protection against the gas.[1]

Why its significant to make a comparison between the German and Allied tactical issues is that it highlights the new style of conflict- the prolonged entrenched warfare- was something that both sides had to adapt to and overcome, for any military facing a new type of conflict there is a rocky learning process before the right ideas can be found and applied.

Jonathon Bailey identifies the tactical problem that the British Army faced in 1914 and equates it to issues with not exploiting the full use of artillery to ‘protect assaulting troops and to be able to fire at unseen targets to protect the troops exploiting the success before the artillery moved forward’.[1] This is because the understanding of how to combine artillery and infantry in the new modern style of warfare was not something that was understood or learnt for a few years and was something that had to be achieved by trial and error.

Therefore, the arguments of the revisionist historian A.J.P Taylor have been criticised in recent years by other historians who realise that placing the sole blame for any tactical errors on the British generals isn’t always accurate as there’s more depth to the decisions than laziness or lack of effort.[1]

Adjusting to Trench Warfare

When the British army began to dig in, they faced a new difficulty to find a solution to, and this was the importance of snipers. In the previous wars, large full-scale infantry and cavalry attacks were some of the most important tactics that would lead to success. But in an entrenched stalemate, this wasn’t often a viable way to attack, so new ideas had to be found, an important individual in the development of sniping tactics was Major H Hesketh- Prichard who published his personal account of trench warfare and sniping in WW1.

‘Sniping, which is to be defined in a broad way as the art of very accurate shooting from concealment or in the open, did not exist as an organized thing at the beginning of the war. The wonderful rapid fire which was the glory of the original expeditionary force was not sniping, nor was it beyond a certain degree, accurate. It’s aim to was to create a ‘beaten zone’ through which no living thing could pass, and this business was not best served by very accurate individual shooting. But when we settled down to trench warfare and even the most skilful may spend a month in the trenches without ever seeing a whole German. When during the day one got but a glimpse or two of the enemy, there arose this need for very accurate shooting.’

Major H Hesketh- Pritchard, Sniping in France

Planning for the Somme

A lot of tactical planning went into the plans for the Somme offensive in 1916, especially focusing on the movements of the infantry as they had one of the most important jobs when it came to pushing the German lines back.

Ideas for the Somme Offensive can be seen as originating from the Chantilly Conference on the 6th of December 1915 that concluded Allied strategy for the following year was to be large-scale offensives on all fronts.[1]

When the Somme Offensive was being planned in more depth, it was intended to be a joint Anglo-French attack but the French capability to take part started to decline due to the German attacks on Verdun. This placed more pressure on Sir Douglas Haig to launch the offensive to alleviate the pressure on the French and General Joffre is quoted by Winters and Baggett to have said that if an attack isn’t launched soon the French army would ‘cease to exist’.[2]

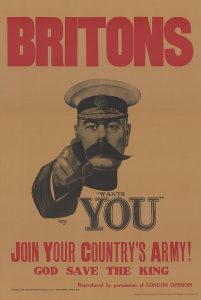

Due to the small size of the original BEF, many mass volunteering drives were set up in Britain with Lord Kitchener as the face of the scheme. When designing this Kitchener was hoping for 100,000 men to sign up to avoid the use of conscription.[3] By the end of 1914 the amount of men who had signed up totalled 1,186, 337, this shows that the ‘Your country needs you’ posters had been incredibly successful in convincing young men to volunteer.[4]

Kitchener’s Volunteer army were very significant when it came to the Battle of the Somme in 1916 as it was the first time that many of them had experienced warfare and trench life. It also made the plans of a large-scale attack more viable due to having a much larger attacking force than in previous years of the war.

Brief timeline of the Somme Offensive

1st July- The Somme Offensive begins along a 25-mile front

14th July- British breakthrough the German second line with cavalry and capture Trones Wood, Longueval and Bazentin-le-Petite finishing the first phase of the offensive

August- more fierce fighting on the Somme but the lines were scarcely changing

15th September- Battle of Fleurs Courcelette- success partly due to the British use of tanks

25th September- Battle of Morval and Thiepval ridge allow for the allies to continue their advance

13th November- Battle of Ancre starts the 4th phase of the Somme Offensive

18th November- End of the Somme Offensive- in total the allies only gained 5 miles of land at the cost of at least 620,000 lives.[1]

Tactics During the Somme

This section will detail a few of the most significant tactics used by the British army across the Somme offensive that are useful to understand when looking at how these tactics went on to be changed and improved.

The Somme Offensive, although officially starting on the 1st of July 1916, was preceded by a week-long artillery bombardment as a way of destroying the German defences and barbed wire as well as their morale. The British generals believed that after a bombardment of this size, the attack would be a simple walk over and the infantry would just have to deal with a few survivors. This was soon discovered to be very false. From the words of a German soldier who survived the battle-

For seven days and seven nights our German soldiers had nothing to drink or eat just constant fire, shell after shell bursting upon us. And then the British Army went over the top. Our gunners crawled out of their bunkers and opened terrific fire…

Stephen K Westmann, German Army Medical Corps

This was because the German bunkers were often many meters underground and were made of concrete, this meant that they were a lot harder to destroy with the artillery power and shells that the British army were using at the time.[1] Meaning most of the Germans survived and were prepared for an attack as a strong artillery bombardment was now recognised as a sign that an infantry attack was coming. And as soon as the British began to make their way out of the trenches, walking as they were told to do, they were easy targets for the German machine guns.

After the initial wave of infantry men were killed by the German machine guns the next wave had no choice but to carry on, this ended in 56,000 injured British and Empire soldiers with an estimated 20,000 of those dead, making it the bloodiest day in British military history to date.[2]

The ‘creeping barrage’ is a tactic that uses a joint infantry and artillery attack that is now associated with the First World War and specifically the Battle of the Somme, even though the tactic was originally developed and used in 1913 by the Bulgarian artillery in the Siege of Adrianople (Edirne) in the First Balkan War.[3] While in theory it could be a very useful tactic to protect the infantry from the German machine guns as well as helping to clear the way for further advancements, in practice it proved to be more difficult.

This was often due to the issues with communication between those in charge of the infantry advancements and the guns providing the barrage, as there was no simple way to keep in contact about the rate of advancement and where to move the bombardment to.[4] It also was risky for these reasons as is it could cost the lives of the advancing infantry if the range was not calculated properly.

A precursor to the more successful uses of different sections of the army together can be seen in the first use of tanks at the Battle of Fleurs-Courcelette on the 15th of September.[5]These were a sign of the British army developing new tactics to face the challenges of modern warfare. However, even though the tanks were successful to a degree- such as exploiting the element of surprise- the models in use were still too slow, heavy and difficult to maintain in the field with many getting stuck in the mud of No Man’s Land.

Perceptions about the Battle of the Somme

What Gettysburg is to America, Verdun is to France and the Somme and Passchendaele are to Britain’

Jay Winters and Blaine Baggett, 1914-1918 the Great War and the shaping of the 20th Century

The Battle of the Somme evokes futility, flawed leadership and the snuffing-out of public innocence’

Joshua Levine, Forgotten Voices of the Somme

Its widespread adoption came only during the Battle of the Somme, which may thus be seen as a sort of tactical watershed’

Paddy Griffith, British Fighting Methods in the Great War

These three historians all have slightly different opinions on how best to perceive the Battle of the Somme and reasoning as to why. The idea of futility is an understandable position to take when reviewing this battle within the context of the war because the land gained for lives lost doesn’t seem to make sense or seem worthwhile. But regardless this battle is something that has earned a place in the collective memory of the First World War and how its perceived is important.

‘The loss of a loved one is bad enough. To be constantly told, quite erroneously that he died for nothing must be even worse’

Gary Sheffield, Forgotten Victory.

This is something that Gary Sheffield is passionate about and covers in his book Forgotten Victory. When this was published in 2001 it was found to be very controversial especially with his opinions on how the Somme should be remembered. This is because he disagrees with the label of ‘futile’ for the offensive as it implies that the men who fought and gave up their lives were doing it for no good reason, this is then disrespectful and upsetting to those families who lost their sons, brothers and fathers. Because it implies their sacrifice was for nothing.[1]

Tactics After the Somme

Tactics after the Somme

What started to become clear after the Somme Offensive was that ‘organizational flexibility’ was vital to overcoming the struggles of the modern style of warfare.[1] What this means is that for there to be a large-scale victory there needed to be a more combined style of fighting meaning that different units were working alongside each other for similar goals instead of being isolated and working independently.

This is shown in the changes that were made to the way that soldiers were told to make attacks on enemy trenches as infantry attacks became more varied. Trevor Yorke describes, this as including small groups of men crawling down sap trenches through cuts that had already been made in the barbed wire to attack strong points and then wait for the ‘main body’ of reinforcements to come.[2]

Trevor goes on to explain why this is significant by detailing the changes in ambitions and artillery placement, which is something that Jonathan Bailey also attributes to the closing years of the war. This is because the achieved positions would be solidified before any further advancements were made making it harder for a German counterattack and allowing for a stronger defence in the event of one.

Paddy Griffith and Gary Sheffield both support the idea that after the Somme, new tactics were being improved and made more efficient, Griffith highlights this by showing how the infantry changed their approach to tactics and ‘seems to have persuaded it to make better use of the resources which lay to hand in the battalion itself’.[3] In addition to this Gary Sheffield has gone on to add that the Second Passchendaele in 1917 is clear evidence of the BEF improving their use with the ‘bite and hold’ technique that allows for the slow attrition of German positions.[4]

These tactical changes going from the large-scale full-frontal attack on the German trenches by the Infantry following a large artillery bombardment which lost the element of surprise to the smaller attritions and solidifying positions shows a clear improvement of the generals understanding of modern warfare and what tactics worked the best.

There is a clear difference between the Somme and the last two years of the war which some historians have attributed to a learning curve, but with a situation such as this with so much trial and error the learning process is a lot rockier than can be attributed to a simple learning curve. It is more important to look at how the tactics changed and developed without trying to simplify it, there is a lot more complexity that comes with tactics such as their wider perceptions and how this affects the families who lost loved ones, that the most important thing to do is understand the tactical changes and the context in which they occurred.

Bibliography

Bailey, Jonathan, The First World War and the Birth of the Modern Style of Warfare, The Strategic and Combat Studies Institute, Surrey, 1996.

Banks, Arthur, A Military Atlas of the First World War, Leo Cooper, London, 1989

Chandler, David (ed), The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army, Oxford University Press, New York, 1994.

Chandler, David, The Dictionary of Battles: The World’s Key Battles from 405bc to Today, Ebury Press, London, 1987.

Corrigan, Gordan, Mud, Blood and Poppycock, Cassel Military Paperbacks, London, 2004.

Grant, R.G, Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat, Dorling Kindersley Limited, London, 2010.

Griffith, Paddy, British Fighting Methods in the Great War, Frank Cass Publishers, London, 1998.

Hesketh-Pritchard, H, Sniping in France: How the British Army Won the Sniping War in the Trenches, Pen and Sword Military, Barnsley, 2014.

History.com editors (January 2021) Battle of the Somme, available at: Battle of the Somme – Deaths, Battles & Legacy – HISTORY (Accessed 10/12/21)

Keegan, John, The First World War, Hutchinson, London, 1998.

Levine, Joshua, Forgotten Voices of the Somme: The Most Devastating Battle of the Great War In the Words of Those Who Survived, Ebury Publishing, London, 2009.

Lewis-Stempel, John, The Autobiography of the British Soldier: From Agincourt to Basra in His Own Words, Headline Publishing Group, London, 2007.

Ministry for Culture and Heritage (April 2021) The Creeping Barrage, available at: The creeping barrage | NZHistory, New Zealand history online (Accessed 06/01/2022)

Sheffield, Gary, Forgotten Victory: The First World War Myths and Realities, Sharpe Books, (no city of publishing available), 2018

Simkin, John, (January 2020) First World War: The German Army, available at: First World War: The German Army (spartacus-educational.com) (Accessed 05/01/2022)

Warner, Philip, World War One: A Chronological Narrative, Pen and Sword Books, Barnsley, 2008.

Watson, Alexander, (January 2014) Recruitment: Conscripts and Volunteers During WW1, available at: Recruitment: conscripts and volunteers during World War One – The British Library (bl.uk) (Accessed 07/01/2022)

Winter, Jay, Baggett, Blaine, 1914-1918: The Great War and the Shaping of the 21st Century, BBC Books, London, 1996.

Yorke, Trevor, The Trench: Life and Death on the Western Front 1914-1918, Countryside Books, Newbury, 2014.

[1] Bailey, Jonathan, The First World War and the Birth of the Modern Style of Warfare (Strategic and Combat Studies Institute, Surrey, 1996) P18

[2] Yorke, Trevor, The Trench: Life and Death on the Western Front 1914-1918 (Countryside Books, Newbury, 2014) P51-52

[3] Griffith, Paddy P17

[4] Sheffield, Gary, P262

[1] Sheffield, Gary, Forgotten Victory (Sharpe Books, no city of publishing available, 2018) P5

[1] Yorke, Trevor, The Trench: Life and Death on the Western Front 1914-1918 (Countryside Books, Newbury, 2014) P30

[2] Scrivenor, Patrick, ‘The Two World Wars’, The Dictionary of Battles (Ebury Press, London, 1987) P175

[3] Ministry for Culture and Heritage, (April 2021) The Creeping Barrage, available at: The creeping barrage | NZHistory, New Zealand history online (Accessed 06/01/2022)

[4] Griffith, Paddy, ‘The Extent of Tactical Reform in the British Army’, British Fighting Methods in the Great War (Frank Cass Publishers, London, 1998) P11

[5] Scrivenor, Patrick, ‘The Two World Wars’, The Dictionary of Battles (Ebury Press, London, 1987) P176

[1] Hook, Alex, World War One Day by Day (Grange Books, Kent, 2004) Pp104-113

[1] Levine, Joshua, Forgotten Voices of the Somme: The Most Devastating Battle of the Great War in the Words of Those Who Survived (Ebury Publishing, London, 2009) P1

[2] Winters, jay, Baggett, Blaine, 1914-1918: The Great War and the Shaping of the 20th Century (BBC Books, London, 1996) P179

[3] Warner, Philip, World War One: A Chronological Narrative (Pen and Sword Books, Barnsley, 2008) P44

[4] Watson, Alexander, (January 2014) Recruitment: Conscripts and Volunteers During World War One, available at: Recruitment: conscripts and volunteers during World War One – The British Library (bl.uk) (Accessed 07/01/2022)

[1] Sheffield, Gary, Forgotten Victory: The First World War Myths and Realities (Sharpe Books, no city of publishing available, 2018) P139

[1] Bailey, Jonathan, The First World War and the Birth of the Modern Style of Warfare (Strategic and Combat Studies Institute, Surrey, 1996) P12

[1] Bailey, Jonathan, The First World War and the Birth of the Modern Style of Warfare (Strategic and Combat Studies Institute, Surrey, 1996) P12

[1] Grant, R.G, Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat (Dorling Kindersley Limited, London, 2005) P273

[2] Sheffield, Gary, Forgotten Victory: The First World War Myths and Realities (Sharpe Books, no city of publishing available, 2018) P139

[1] Chandler, David (ed), The Dictionary of Battles: The World’s Key Battles from 405BC to Today (Ebury Press, London, 1987) P173

[2] Hook, Alex, World War One Day by Day (Grange Books, Kent, 2004) P22

[3] Scrivenor, Patrick ‘The Two World Wars’, The Dictionary of Battles: The World’s Key Battles from 405BC to Today (Ebury Press, London, 1987) P174

[1] Keegan, John, The First World War (Hutchinson, London, 1998) Pp108-109

[2] Banks, Arthur, A Military Atlas of the First World War (Leo Cooper, London, 1989) P47

[1] Travers, Tim, ‘The Army and the Challenge of War 1914-1918’, The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army (Oxford University Press, New York, 1994) P215

[2] Simkin, John, (January 2020), First World War: The German Army, available at: First World War: The German Army (spartacus-educational.com) (Accessed 05/01/2022)

[3] Warner, Philip, World War One: A Chronological Narrative (Pen and Sword Books, Barnsley, 2008) P91

[4] Corrigan, Gordon, Mud, Blood and Poppycock (Cassel Military Paperbacks, London, 2004) P64

[1] Corrigan, Gordon, Mud, Blood and Poppycock (Cassel Military Paperbacks, London, 2004) P64

[1] Simkin, John, (January 2020), First World War: The German Army, available at: First World War: The German Army (spartacus-educational.com) (Accessed 05/01/2022)

[2] Warner, Philip, World War One: A Chronological Narrative (Pen and Sword Books, Barnsley, 2008) P91

[1] Travers, Tim, ‘The Army and the Challenge of War 1914-1918’, The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army (Oxford University Press, New York, 1994) P215

[1]History.com editors, (January 2021) Battle of the Somme, available at: Battle of the Somme – Deaths, Battles & Legacy – HISTORY (Accessed 10/12/2021)