By: Adam Bradley James

Today in Britain there is an influential image of the British Army as a force of victims not professional warfighters. Its members are perceived to be failed by the state and forced into harm’s way for reasons that neither the Army nor the government will adequately explain. [1] The British Army has worsened this situation by withdrawing from the debate about its missions, instead choosing to hide the use of force from the British public.

This withdrawal from democracy and the popular image of British soldiers as victims of war has the potential to seriously damage the British Army as a warfighting organisation. The British Army can only conduct its operations as long as it has the support of the British public to do so. If the public is unwilling to support sending its professional soldiers into harm’s way, then the British army will become combat ineffective and a dead-weight around the neck of the British state. [2]

Summary

This page has identified two issues with the British Army’s image in battle that threaten its ability to operate as a warfighting organisation. The first is the view of soldiers as victims, which has reduced the willingness of the British public to support the British Army’s deployment. The second issue is that as a result of this diminishing support for its deployment, the British Army has undertaken a strategy of hiding the use of force from the public. However, this strategy is demonstrated here to further reduce the ability of the British Army to operate as a warfighting organisation.

The recommended solutions made here are inexpensive and can be summarized as making the use of force more transparent. This should be pursued with the aim of building a detailed picture of ongoing operations for the British public. In addition, it is also recommended that the Army change the perception of its soldiers through leveraging its influence with influential civilian organisations to change the focus of their messaging. While it is also argued that both of these policies should be supported by an effort to re-individualise British soldiers in the eyes of the public, by entrusting them to speak to the media.

The British Soldier’s Image Problem

“Our troops are fighting a war as professional soldiers, not victims, and the sooner everyone switches onto that fact the better”.[3]

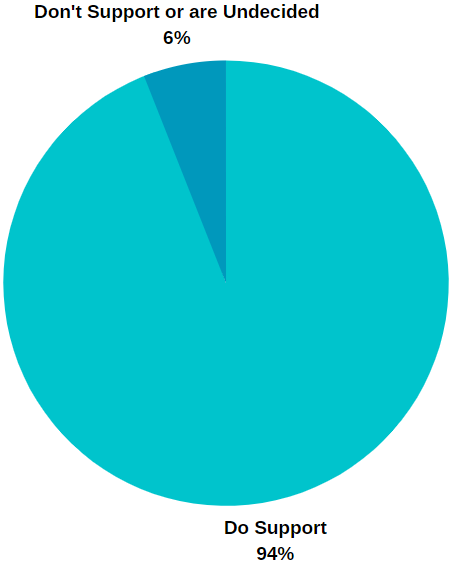

Figure 1. Do you support soldiers who have recently served in Iraq? Poll conducted by British social attitudes 2012.

British Social Attitudes. ‘The UK’s Armed Forces: public support for the troops but not their missions?’ (Great Britain, National Center of Social Research, 2012). P.149. (Graph Created by Author).

The issue of British soldiers being perceived by the public as victims, is often missed in analysis that shows the high esteem they are held in by the public, 98% of which claim to respect the armed forces.[4] However, the problem first becomes apparent in the media’s portrayal of British soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan. Where from the beginning British casualties were presented as victims of crimes. The first casualties of the occupation of Iraq were reported in Britain’s media under headlines such as the following, ‘Tributes and tears as Britain mourns its first victims’.[5] While in 2010, 238 articles were published in Britain referring to acts of heroism in Afghanistan. [6] However, the very few of these articles depicted British soldiers as anything but heroic victims of a tragedy, with no mention that they were professionals who were fighting a battle.[7] This is exemplified in headlines such as, ‘Bomb hero soldier is 108th victim’ and ‘Afghan blast victim was a true hero say family and colleagues’.[8] This narrative went as far as to mislead the public, with soldiers being referred to as ‘Hercules crash victims’, after their helicopter had not crashed but had been shot down by enemy fire.[9]

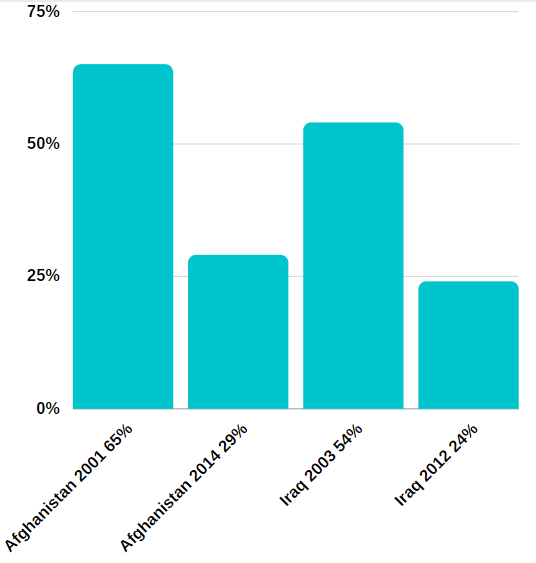

The impact of this image is evident in the divide between the the support for veterans of Britain’s recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan and the public’s lack of support for the conflicts themselves. (see figures 1 and 2). These conflicts were unpopular for a number of reasons. However, the research conducted here shows that the image of British troops create during these conflicts has created a lasting problem, because the public has become unwilling to allow the British Army to perform its role as a fighting organisation. [10]

A significant cause of this is the image of British soldiers victims. In this view, the distinction between a solider who accepts unlimited liability in order to serve his country and a civilian who is the victim of a crime is removed. The Army is in this way transformed from an organisation of professional warfighters, into a group of victims who are perceived only suffer violence inflicted upon them by the enemy.

British Foreign Policy Group, ‘Public Attitudes to Military Intervention’, (London, British Foreign Policy Group, 2020). P.9. &. British Social Attitudes. ‘The UK’s Armed Forces: public support for the troops but not their missions?’ (Great Britain, National Centre of Social Research, 2012). P.147. (Graph Created by Author).

When the public and the media depict members of the British army in this way, their agency is removed, they are made into hollow figures upon whom narratives of humanitarianism and litigation culture are projected. [11] This hollowed out image of British soldiers is better able to be stomached by the public, even at a time when the Army has failed to generate public support for the soldiers’ missions. [12]

“There is a culture of risk aversion developing in society which is anathema to servicemen. We are not foolhardy but our profession requires a degree of decisiveness, flair and courage.”[13]

The effect of this image is evident throughout the British army’s campaign in Afghanistan, where the public became so casualty adverse that Operation HERRIC became derailed by the need to avoid casualties.[14] Strategies of manoeuvre and attack were abandoned,[15] while initiative was stifled by political oversight of the battlefield.[16] By the end of the operation, force protection had become the driving force behind decision making rather than the search for victory.[17]

To put it simply, because the public now perceives British soldiers to be victims rather than warfighters, its aversion to casualties has risen to such a level that it has began to seriously damage the Army’s ability to win on the operational level.

The British Army’s Rout from the Battle for Public Understanding

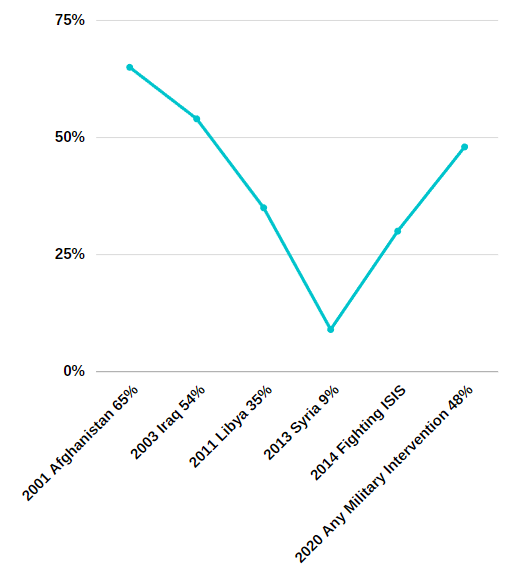

Figure 3. Changing support for British Army deployments since 2001.

British Foreign Policy Group, ‘Public Attitudes to Military Intervention’, (London, British Foreign Policy Group, 2020). P.4-9. (Graph Created by Author).

Compounding the problems caused by the image of British soldier’s as victims, is how little information the British Army chooses to provide the public about its ongoing operations.

The result of this secrecy has been that the British public increasingly does not understand the British Army’s missions and therefore does not support them. While in addition to this, the lack of information being provided to the public has caused a disproportionate amount of time in the media to be dedicated to discussing and reporting on the casualties suffered during combat operations.[18] Furthermore, this focus has made it common for members of the British public to have inflated beliefs about the number of British casualties suffered in Iraq and Afghanistan. [19]

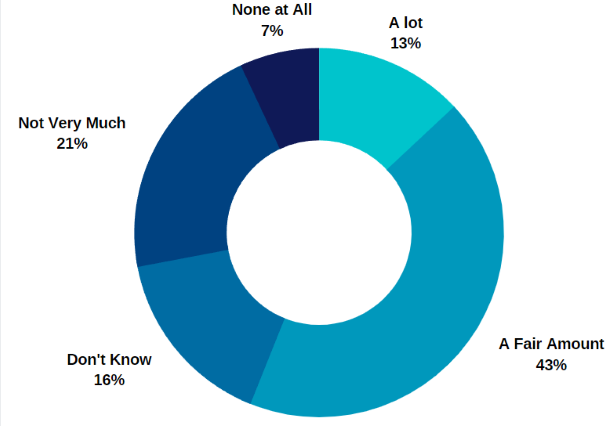

YouGov, ‘Confidence in the British armed forces in defence’. Available at: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/economy/trackers/confidence-in-the-british-armed-forces-in-defence. [Accessed 15/12/2021]. (Graph Created by Author).

By creating a situation where casualties are being discussed without any context of the mission the casualty was incurred upon the British Army is making the British public aversion to casualties worse. Because the British public’s willingness to stomach casualties is closely linked to its opinion of the mission the tragedy occurred upon and whether the mission was a success. [20]

The cause of this situation is that, the British Army and the Government have taken away from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that the public is unwilling to support the use of force. A conclusion which certainly appears substantiated by the decline in support for military interventions over the course of those conflicts ( See Figure 3).

What is not understandable, is that instead of attempting to convince the public of the utility of force, the British Army has instead chosen a policy of disclosing as little information as possible regarding the activities of British troops.[21] However, this approach will only worsen the public’s wiliness to deploy the Army, because it is a policy of choosing not to change public opinion but instead to conduct warfare without public approval in a democratic state.

The result of this approach, is that it has contributed to the British public becoming divided over whether it trusts the the British Army to succeed in its missions. In 2021, just 56% of the British public had any confidence in the British Army’s ability to protect the UK in wartime (see figure 4).[22] While in the same year, just 59% of the public were confident of the Army’s ability to take part in operations overseas. [23]

The research conducted here, demonstrates that the British Army’s current strategy of hiding the use of force is not a productive strategy. In fact. it is seriously harming the ability of the British Army to perform its role in Britain defence.

Recommendations for Generating Support for the Army as a Fighting Organisation

‘Politicians, media and the public need to understand that risk thresholds need to be reset. The Army must influence the debate, win it, and rebalance tolerance for risk. We must regain an offensive mindset’.[24]

Summary of Recommendations.

- Encourage change in the way British service charities represent British soldiers.

- Re-individualise soldiers by allowing them to speak publicly.

- Redirect public attention away from casualties, by providing a detailed picture of on events as they are happening and to provide context when casualties are suffered.

- Generate support for warfighting operations by providing the public with far more information about ongoing operations, enabling informed opinion-making.

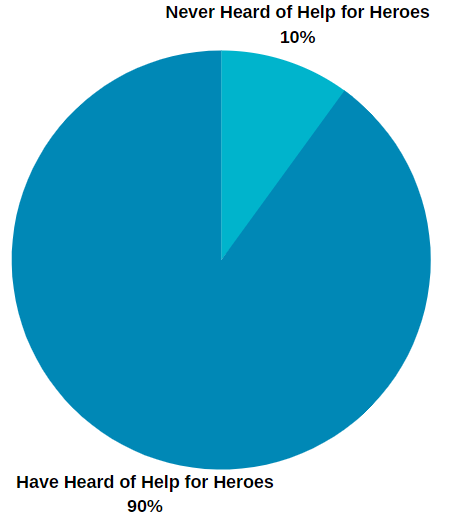

YouGov. ‘Help for Heroes Rating Data’. Available at: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/explore/not-for-profit/Help_for_Heroes?content=articles. [accessed: 27/12/2021]. (Graph Created by Author).

Both of the issues presented here have inexpensive solutions found in changing the way the British Army engages with the public.

Firstly, the Army can begin to combat the victim narrative by changing the way it is depicted by service charities such as Help for Heroes. The UK’s service charities have been exceptionally successful in ensuring that British veterans receive public support, because of this success, the Army has come to rely on these charities to depict a positive image of its soldiers.[25] However, this is not their function and by joining the army’s image with that of charities it is promulgating the victim narrative.[26]

Help for Heroes in particular has been used by the Army to generate a positive image of service personnel because of its unmatched reach within the British public, (see figure 5) and has worked closely with the British Army since its founding in 2007. As a result, the Army possesses sizeable influence within Help for Heroes and organisations like it. This could be utilised to motivate a change in focus to also advertise the work veterans did while serving. This could be used to expand the view of British soldiers in the public eye wider than the victims of war, to that of soldiers who made a positive impact on Britain’s security with their service.[27]

Following on from this, the Army must re-individualise British soldiers if it is to reverse their image as victims and replace it with a productive image of professionals with agency.

An excellent and inexpensive way to achieve this would be to trust soldiers once again with a camera as well with a lethal firearm. Soldiers should be allowed to speak to the press as they have in previous conflicts such as Northern Ireland. The British army fears that enabling this may cause a scandal should a soldier speak out of line in the heat of the moment.[28] However, if the Army trusts its service people to remain professional under enemy fire, it should also be able to trust its soldiers to not undermine the mission while in the presence of a reporter. With specialized training this could easily be achieved.

Building upon this, soldiers should also be allowed to weigh in on debates surrounding the armed forces, especially those surrounding the image of the armed forces where their voices are notably absent and allowing damaging narratives to promulgate.[29]

“We are empowered to use lethal force yet there is a reluctance to empower individuals in front of a microphone, camera or internet connected keyboard. Isn’t it about time we were given some media rules of engagement and practiced the contemporary skill of media mission command?”[30]

Continuing with these reforms, if the British Army wants to once again enjoy the support of the public for its missions then it must provide the public with the information it needs to create informed opinions. Success in this direction is achievable because contrary to the Army’s belief, research shows that the British public understands the utility of force when it is justified.[31] It also shows that most voters base their decision on whether to support a military operation upon logical cost-benefit analysis, as well as questioning the morality of the operation.[32] This means that the British Army can effect this opinion-making process if it chooses to engage with it and provide the information the public needs to make an informed decision.

‘There is merit in a wider public and political debate to educate the nation on the operational context and potential risks of operations beyond Afghanistan.’[33]

The most important change that must occur is for the British Army to provide the public with a detailed picture of the operations its soldiers are conducting, their objectives and their progress. This must be done with the aim of enabling the public to feel informed about the conflicts British soldiers are fighting.

Research shows that the British public is willing to support the British Army as a warfighting organisation when it understands the Army’s mission. The clearest example of this is the British public’s support for wars of territorial integrity or the defence of an ally. These are popular with the public because the objectives are easily understood and appear morally legitimate.[34] However if the Army provides enough information, then even complex missions such as state-building will become widely understood and more readily supported. Although the idea of working with the media may be abhorrent to many army officers, this approach will be enabled by the British media. News outlets will dissect and explain the information the Army is providing about ongoing operations and make it accessible to the widest possible range of British citizens.

This approach will also serve to move the public’s focus away from the casualties sustained by the Army, because more air-time will be spent covering the Army’s current objectives, its progress and the theatre of operations. Furthermore, this approach will provide context to the casualties that are sustained, increasing the chance that the public may see their sacrifice as justified or necessary. This is a crucial change because as stated earlier, the public’s acceptance of casualties is closely associated with its approval of mission the casualty occurred upon.[35] Therefore, by providing the details of the British Army’s missions upon which casualties will inevitably be incurred, the British public’s casualty aversion can likely be reduced.

The greatest threat to trust arises when expectations are disappointed. Expectations should be realistic, and performance and expectations should be monitored in time and adjusted.[37]

This approach can be strengthened if the Army chooses to under-promise and overachieve concerning the objectives of its operations.[36] In the aftermath of the defeats in Iraq and Afghanistan public confidence in the British Army to succeed is significantly lacking (see again figure 4). The British Army can however reverse this trend, by being conservative in its promises and making the public’s expectations of the outcome of an operation easily achievable. The organisation can then appear as a fighting force that consistently over-achieves and can be trusted once again with warfighting operations.

A significant objection to providing more detailed information on the Army’s operations, is likely to be that to the British public the reality of warfare is unpalatable. In particular, the nature of the British Army’s doctrine of attack, which places emphasize upon close quarters violent action,[38] will be feared to cause a negative reaction in the humanitarian minded public.

“For the British infantry…the default overall tactical approach in…contact…is to close with and destroy the enemy, using overwhelming violence“.[39]

However, the fluidness of British public opinion and the nature of British doctrine will counteract this. Firstly, historical evidence shows that when the British public supports the Army’s mission it is not repulsed by the use of violence. In recent conflicts that were well understood and widely supported, such as the Falklands War, the British public was more than willing to support the use of the maximum amount of violence needed to to achieve the mission.[40] We can confer from this that if the British Army can generate greater support for its missions, then it will not have to fear losing large amounts of this support through the violent nature of its role as a warfighting organisation.

The second reason that the open information approach will be able to overcome this objection, is because of the British Army’s minimum force philosophy.[41] This concept means that extreme importance is placed upon fighting within the bounds of international law and as far as possible limiting the suffering caused by war.[42] There should therefore be no fear that the public will be repulsed by the Army’s use of force, because the British Army can be trusted to ensure its use is moral and proportionate. Something that would further improve if unit commanders were aware that their actions were likely to be in the pubic eye.

Important Conclusions

- The research presented here demonstrates two clear problems in the current image of the British Army in battle;

- That there is a perception of British soldiers as victims, which is reducing the public’s willingness to deploy the Army and increasing its casualty aversion.

- The British Army is making the problem of the lack of support for its use worse, by hidingthe use of force and the details of its missions from the public.

- The solutions to these problems are firstly to draw renewed attention to the work and professionalism of British soldiers, through leveraging the Army’s influence within service charities.

- Secondly to re-individuals British soldiers by trusting them to speak to the public.

- However, most importantly, the British Army must make its operations more transparent, in order to further public understanding and generate public support for its deployments.

- These recommendations have been chosen because they do not involve any significant cost on the part of the British Army, nor are they hard to achieve. They are therefore, perfectly suited for a time in which the Army’s size and budget are shrinking as we are currently experiencing.

Further Reading

- Alexander DA, Dandeker C, Fear NT, Gribble R, Klein S. ‘British Public Opinion after a Decade of War: Attitudes to Iraq and Afghanistan’, in Politics, 35 (2015). Pp.128-150.

- British Army, ‘Directorate land warfare: Operation HERRICK Campaign Study’. (Great Britain, Land Warfare centre, 2015).

- British Foreign Policy Group, ‘Public Attitudes to Military Intervention’, (London, British Foreign Policy Group, 2020).

- British Social Attitudes. ‘The UK’s Armed Forces: public support for the troops but not their missions?’ (Great Britain, National Centre of Social Research, 2012).

- Burnwell, O, ‘Society and the British Army: Implications for Fighting Spirit’,(USA, United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2017).

- Ferguson, N and McGarry, R. ‘Exploring Representations of the Soldier as Victim: From Northern Ireland to Iraq’, in Representations of Peace and Conflict (Rethinking Political Violence). Edited by, Gibson, S and Mollan, S (USA, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). Pp.120-142.

- Ledwidge, F. Losing Small Wars: British Military Failure in Iraq and Afghanistan, (London, Yale University Press, 2011).

- McCartney, H. ‘Hero, Victim or Villain? The Public Image of the British Soldier and its Implications for Defence Policy’, Defence & Security Analysis, 27 (2011).

- Nooteboom, B. ‘The Synamics of Trust: Communication, Action and Third Parties’, in Trust : Comparative Perspectives. Edited by, Sasaki, M and Marsh, M. (USA, BRILL, 2012). Pp. 8-30

- RAND Corporation. ‘The Utility of Military force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain’, (United States, RAND Corporation, 2020).

- The Guardian. ‘Defence Chief lays into cultue of ‘risk aversion’. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2000/dec/20/richardnortontaylor [Accessed: 16/12/2021].

- Thornton, R. ‘The British Army and the Origins of its Minimum Force Philosophy’, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 15 (2004). Pp. 83-106.

- Wavell Room, ‘Winning The Narrative- An Army Officer’s Perspective’. Available at: https://wavellroom.com/2018/07/05/how-do-you-win-the-narrative/ [Accessed: 17/12/2021].

References

[1] McCartney, H. ‘Hero, Victim or Villain? The Public Image of the British Soldier and its Implications for Defence Policy’, Defence & Security Analysis, 27 (2011). P.43.; RAND Corporation. ‘The Utility of Military force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain’, (United States, RAND Corporation, 2020).p.2.

[2] RAND Corporation. ‘The Utility of Military force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain’, (United States, RAND Corporation, 2020). P.3.

[3] Andy McNab quoted in, (Ferguson, N and McGarry, R. ‘Exploring Representations of the Soldier as Victim: From Northern Ireland to Iraq’, in Representations of Peace and Conflict (Rethinking Political Violence). Edited by, Gibson, S and Mollan, S (USA, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). P.127).

[4] British Social Attitudes. ‘The UK’s Armed Forces: public support for the troops but not their missions?’ (Great Britain, National Centre of Social Research, 2012).P.141.

[5] RAND Corporation. ‘The Utility of Military force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain’, (United States, RAND Corporation, 2020). P.8. [6] Ferguson N and McGarry, R. ‘Exploring Representations of the Soldier as Victim: From Northern Ireland to Iraq’, in Representations of Peace and Conflict (Rethinking Political Violence). Edited by, Gibson, S and Mollan, S (USA, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). P.127

[6] McCartney, H. ‘Hero, Victim or Villain? The Public Image of the British Soldier and its Implications for Defence Policy’, Defence & Security Analysis, 27 (2011). P.43.

[7] Ibid

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ferguson, N and McGarry, R. ‘Exploring Representations of the Soldier as Victim: From Northern Ireland to Iraq’, in Representations of Peace and Conflict (Rethinking Political Violence). Edited by, Gibson, S and Mollan, S (USA, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). P.127

[10] RAND Corporation. ‘The Utility of Military force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain’, (United States, RAND Corporation, 2020). P.8.

[11] McCartney, H. ‘Hero, Victim or Villain? The Public Image of the British Soldier and its Implications for Defence Policy’, Defence & Security Analysis, 27 (2011). P.47

[12] Ibid.

[13] The Guardian. ‘Defence Chief lays into cultue of ‘risk aversion’. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2000/dec/20/richardnortontaylor [Accessed: 16/12/2021].

[14] Burnwell, O , ‘Society and the British Army: Implications for Fighting Spirit’,(USA, United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2017).p.35

[15] British Army, ‘Directorate land warfare: Operation HERRICK Campaign Study’. (Great Britain, Land Warfare centre, 2015). P. 2-1_2.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] British Army, ‘Directorate land warfare: Operation HERRICK Campaign Study’. (Great Britain, Land Warfare centre, 2015). P. 2-1_2.

[19] Alexander DA, Dandeker C, Fear NT, Gribble R, Klein S. ‘British Public Opinion after a Decade of War: Attitudes to Iraq and Afghanistan’, in Politics, 35 (2015). p.139

[20] Burnwell, O, ‘Society and the British Army: Implications for Fighting Spirit’,(USA, United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2017). P.36

[21] Gribble R, Wessley S, Klein S, Alexander DA, Dandeker C, Fear NT. ‘British Public Opinion after a Decade of War: Attitudes to Iraq and Afghanistan’. Politics, 35 (2015). P.139.

[22] RAND Corporation. ‘The Utility of Military force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain’, (United States, RAND Corporation, 2020). P.14.

[23] YouGov, ‘Confidence in the British armed forces in defence’. Available at: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/economy/trackers/confidence-in-the-british-armed-forces-in-defence. [Accessed 15/12/2021].

[24] YouGov, ‘Confidence in the British armed forces military operations overseas’. Available at: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/economy/trackers/confidence-in-the-british-armed-forces-military-operations-overseas. [Accessed 15/20/2021].

[25] RAND Corporation. ‘The Utility of Military force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain’, (United States, RAND Corporation, 2020). P.8

[26] Ibid. P.2.

[27] RAND Corporation. ‘The Utility of Military force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain’, (United States, RAND Corporation, 2020). P.8

[28] RAND Corporation. ‘The Utility of Military force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain’, (United States, RAND Corporation, 2020). P.1.

[29] Wavell Room, ‘Winning The Narrative- An Army Officer’s Perspective’. Available at: https://wavellroom.com/2018/07/05/how-do-you-win-the-narrative/ [Accessed: 17/12/2021].

[30] Wavell Room, ‘Winning The Narrative- An Army Officer’s Perspective’. Available at: https://wavellroom.com/2018/07/05/how-do-you-win-the-narrative/ [Accessed: 17/12/2021].

[31] British Army, ‘Directorate land warfare: Operation HERRICK Campaign Study’. (Great Britain, Land Warfare centre, 2015). P.2-1_2.

[32] RAND Corporation. ‘The Utility of Military force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain’, (United States, RAND Corporation, 2020). P.14

[33] British Foreign Policy Group, ‘Public Attitudes to Military Intervention’, (London, British Foreign Policy Group, 2020). P.4.

[34] Burnwell, O , ‘Society and the British Army: Implications for Fighting Spirit’,(USA, United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2017).p.34.

[35] British Army, ‘Directorate land warfare: Operation HERRICK Campaign Study’. (Great Britain, Land Warfare centre, 2015). P. 2-1_2.

[36] RAND Corporation. ‘The Utility of Military force and Public Understanding in Today’s Britain’, (United States, RAND Corporation, 2020). P.8.

[37] Nooteboom, B. ‘The Synamics of Trust: Communication, Action and Third Parties’, in Trust : Comparative Perspectives. Edited by, Sasaki, M and Marsh, M. (USA, BRILL, 2012). P.26.

[38] Ledwidge, F. Losing Small Wars: British Military Failure in Iraq and Afghanistan, (London, Yale University Press, 2011). P.174.

[39] Burnwell, O, ‘Society and the British Army: Implications for Fighting Spirit’,(USA, United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2017).p.1.

[40] Burnwell, O, ‘Society and the British Army: Implications for Fighting Spirit’,(USA, United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2017).p.34.

[41] Thornton, R. ‘The British Army and the Origins of its Minimum Force Philosophy’, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 15 (2004). P.99.

[42] Ledwidge, F. Losing Small Wars: British Military Failure in Iraq and Afghanistan, (London, Yale University Press, 2011). P.174.